A reflection on Sharks International

In this age of digital communication, do conferences still play an important role in research and conservation? SOSF principal scientist Sarah Fowler thinks so, and she explains why.

Walking along the corridors during coffee breaks at Sharks International in Durban, June 2014, took me back in time. I don’t mean just a few years to the first Sharks International conference in Cairns, Australia, in 2010, but all the way back to 1992 and ‘Sharks Down Under’ in Sydney. That was my first international shark conference. It was a huge eye-opener to a marine ecologist from the United Kingdom, where the subject of shark conservation was rarely mentioned and very few people even knew that there were sharks in British waters.

Although 22 years have passed since then, there were some striking similarities between the two meetings. In Sydney there was a whole symposium on shark-control programmes for bathing beaches (it reached the conclusion that once such programmes are introduced, local politics make it impossible to halt them – so don’t start!). Early results of shark-tagging programmes were presented (using conventional visual tags, naturally) and there were talks warning of the vulnerability of shark species to overfishing, persecution and the threat posed by the steeply rising demand for fins in East Asia during the late 1980s. Most importantly, the delegates of almost a generation ago shared with those of today a contagious fascination and enthusiasm for, and dedication to, these animals.

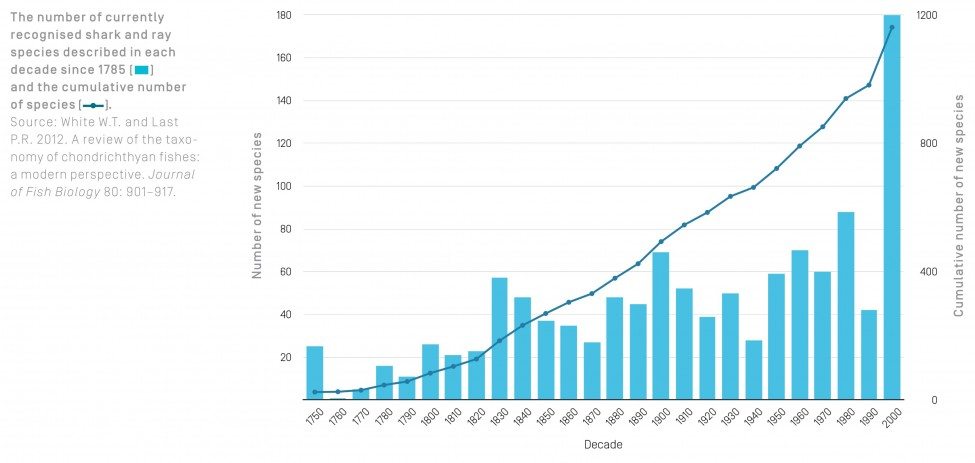

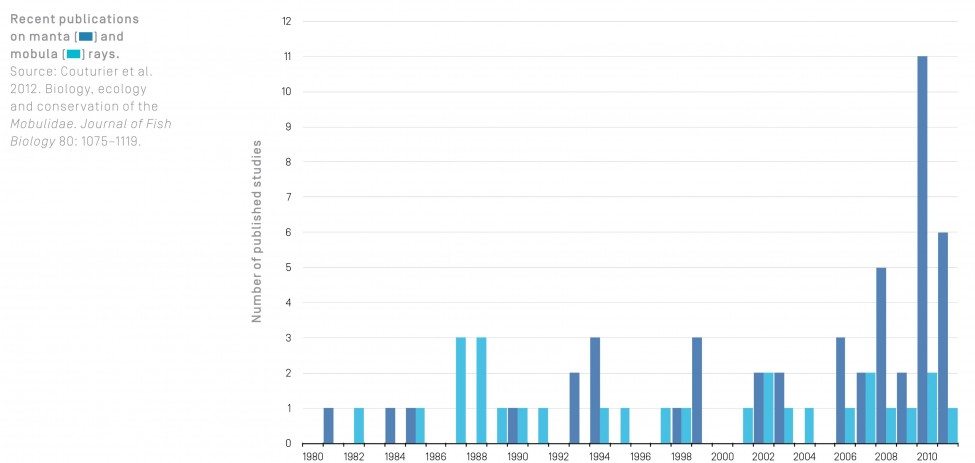

In other respects, however, a great deal has changed in two decades (and I am not just referring to the grey hairs of the ‘Sharks Down Under’ delegates who attended the Durban and many other intervening meetings). Our knowledge of the biology, ecology, species and populations of sharks has undergone a step change during the intervening decades. So too has our awareness that their flatter cousins (skates, rays, guitarfishes and sawfishes) are just as important and many of them are even more seriously threatened.

Technology, too, has advanced at an astonishing rate. Some of the presentations during Sharks International left me open-mouthed in amazement at the huge strides in knowledge made possible by new technology, from acoustic and satellite tags to genetic analyses and novel methods for studying age and growth. No less remarkable is the ease with which such data can now be accessed. Are the stinky undergraduate dogfish dissections that I remember so well obsolete, now that the anatomical imagery presented by Gavin Naylor from the Chondrichthyes Tree of Life is available to all?