Discovering the forgotten sirenian

Elusive and enigmatic, the African manatee faces threats that can only be mitigated when more is known about it. And therein lies the problem: resources for biologists in Africa are rudimentary, to say the least. Lucy Keith Diagne has set up a network to overcome the challenges they face.

Photo by Thomas Peschak

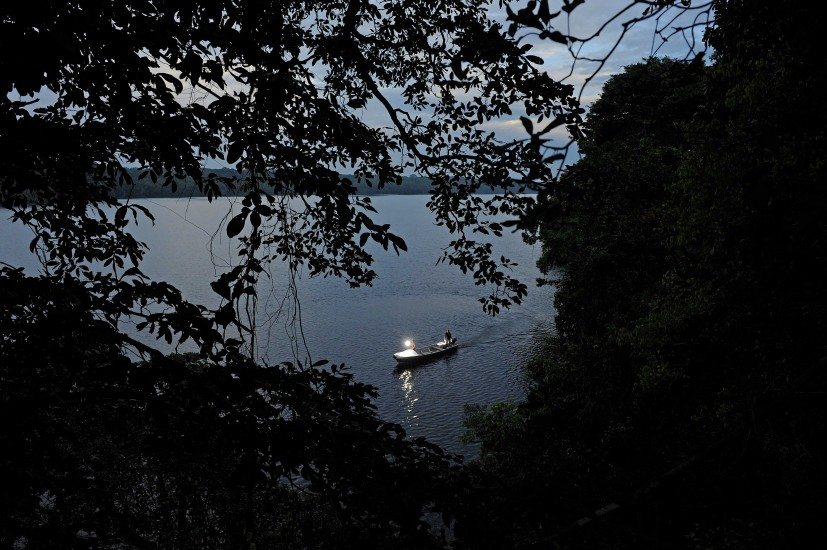

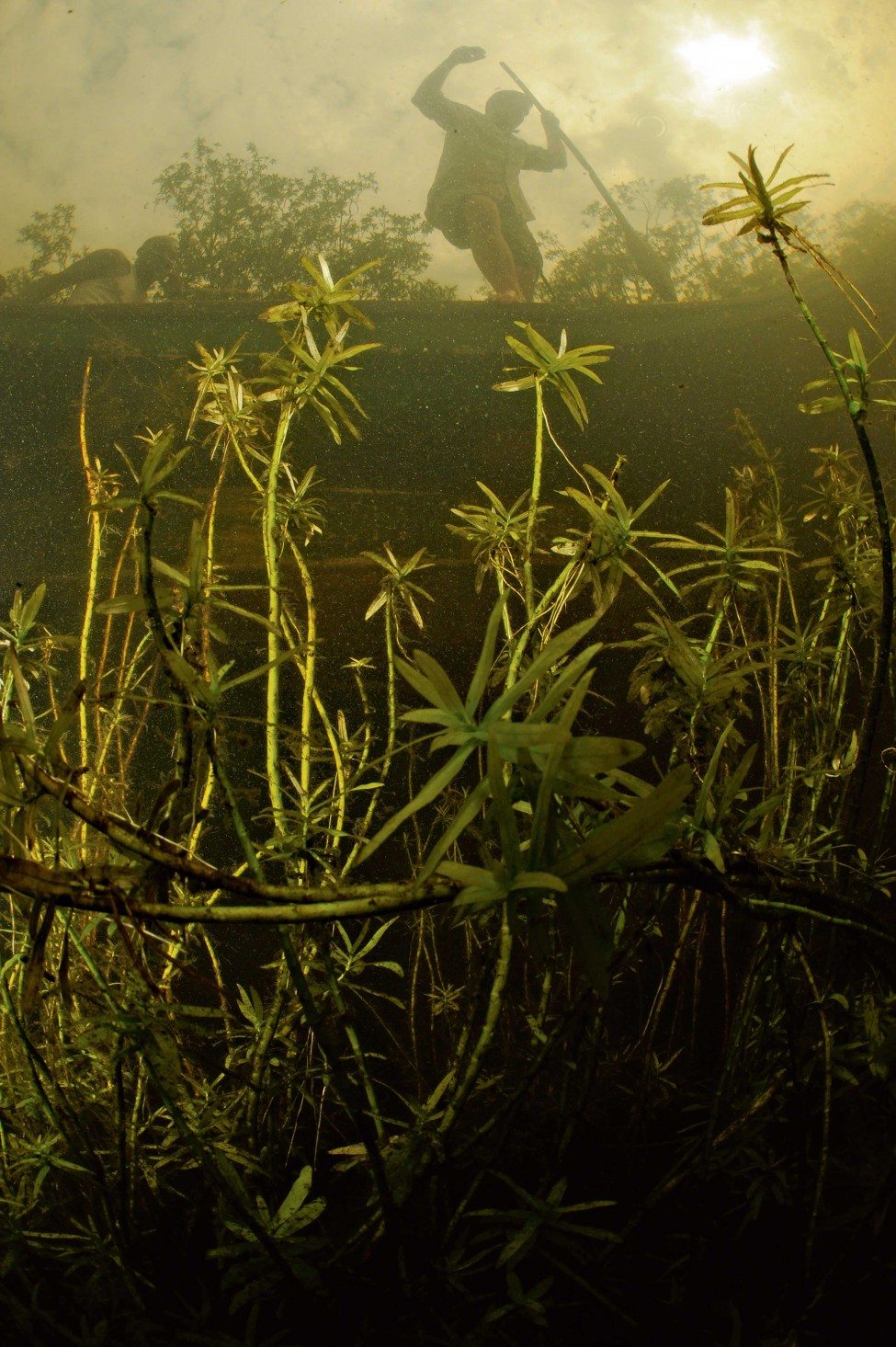

It’s no wonder that many Africans think that ‘their’ manatee is a magical spirit, one they call Mamiwata. The animal is so elusive and lives in such remote, dark, muddy waters that it’s easy to see why it is often likened to an apparition. Just getting a glimpse of a nose or a tail is a rare surprise, and most people outside Africa have no idea that the species exists. Although the African manatee Trichechus senegalensis looks much like its better-known cousin in Florida, it is generally smaller and has more protruding eyes.

We know much less about the African manatee because not only is it more difficult to find and study in the wild, but also there are few resources for biologists in Africa to study it. The lack of research on this species compared to the other manatees has led to it being nicknamed ‘the forgotten sirenian’. According to the IUCN Red List of Threatened SpeciesTM, the African manatee is ‘the least studied large mammal in Africa’. For the past 10 years I’ve been trying to change that. But it hasn’t been easy.

In addition to the challenges to studying them, the threats to African manatees are many. The animals are hunted, accidentally caught in fishing gear and trapped in dams and their habitat is being destroyed. Hunting is intensive in many places and manatee meat is openly sold in markets and restaurants, even though the species is legally protected in every country where it occurs. This is because the meat is considered a delicacy and is a traditional food item in many cultures. In Cameroon, for example, manatee is traditionally served at wedding feasts.

Although there is a lot of legislation to protect the species – national laws in all countries where it occurs and listings on Appendix I of CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species), CMS (Convention of Migratory Species) and the US Endangered Species and Marine Mammal Protection acts – there is little enforcement to deter poachers. Moreover, accurate numbers of manatees hunted and sold have barely been recorded, so there is no information available to compel wildlife law enforcement agencies to administer the laws. As for the other threats, there’s been almost no documentation of manatees caught incidentally in fishing nets or trapped in dams. In recent times hydroelectric and agricultural dams have isolated manatee populations in many major waterways, including the Niger and Senegal rivers and Lake Volta in Ghana. Individuals have also been killed in the dam structures themselves, trapped or crushed in the gates. Another three huge, multi-purpose dams have been under construction along the Niger River since 2008, all of which will restrict manatee habitat further and lead to the genetic isolation of some populations.

Secrets of the African manatee

Although they are found in 21 countries, African manatees are rare and incredibly secretive. Lucy is creating a network of collaborators to help her learn more about this forgotten sirenian and how to conserve it.