Dive tourism dynamics

Wildlife viewing has become a popular form of ecotourism and is considered beneficial to conservation. It does, after all, contribute to local economies and increase support for conservation initiatives. But how does it affect the wildlife being viewed? Having begun to look into the effects of providing food for great hammerhead sharks in Bimini to bring them within reach of ecotourists, Vital Heim has found a whole lot of new questions.

Large-bodied animals often occupy high positions in the food web and, if they are apex predators, they can shape ecosystems. Yet the populations of many such animals are in severe decline because their habitat is being destroyed by human activities or they are being harvested. In the marine realm, large sharks are especially vulnerable because their growth rate is slow, they mature late and their reproductive rate is low. As a result, many shark populations around the world are shrinking significantly. There is increasing evidence that the loss of an apex predator – the function of some shark species as the predator right at the very top of the food chain – can have a far-reaching impact on an ecosystem.

Diving with sharks is gaining in popularity in many parts of the world and nowhere more so than in The Bahamas, which is bucking the trend of global declines in shark populations. Thanks to conservation measures such as a ban on commercial long-line fishing in 1993 and the declaration of The Bahamas as a shark sanctuary in 2011, the populations of various shark species here are healthy – and contributing to the island nation’s popularity as a diving destination. Of the more than US$100-million generated by the Bahamian dive industry each year, a large proportion comes from shark diving.

Many sharks are by nature both rare and elusive, so food is used to attract these marine predators to locations where ecotourists can experience close encounters with them. As yet, however, little is known about the potential effects of provisioning on both the targeted sharks and other species in the vicinity.

The great hammerhead Sphyrna mokarran is a large shark that inhabits coastal waters and open seas in tropical regions around the globe. Typically solitary, it is rarely seen in the wild, yet every winter numbers of this charismatic apex predator congregate in Bimini, a group of small, mangrove-fringed islands at the western edge of the Great Bahama Bank. Divers from all parts of the world are drawn to this seasonally resident population of great hammerheads – and pour into the local economy more than half of the annual revenue generated by shark diving in Bimini.

Its apparently healthy population around Bimini notwithstanding, the great hammerhead is classified as Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Previous research conducted by the Bimini Biological Field Station Foundation (BBFSF) found evidence that several individuals return to Bimini each season. Visual identification played an important part in this research and an ID database currently comprising 35 great hammerheads has been set up. This could be done because individuals have certain characteristics that remain consistent over many seasons: distinctive fin shapes, notch patterns on the first dorsal fin and spot patterns on the belly, for example. Newly identified sharks added to the database each year improve our knowledge of the population’s size and structure.

It is important to understand what could impact the behaviour or movements of the great hammerhead, but no work had been done to investigate the effects of feeding and dive tourism on this species. Other studies on the provisioning of sharks indicated that the impacts were site-specific and species-specific, and even that they may have varied from one individual to another. Our research aimed to describe the behaviour of the great hammerheads at the feeding site in Bimini and determine whether the provisioning and the daily dive tourism activities had an impact on how they used the local space. Thanks to our collaboration with local dive operator Neal Watson’s Bimini Scuba Center, we were able to collect data on every commercial dive led by the company.

Bimini Biological Field Station (BBFS)

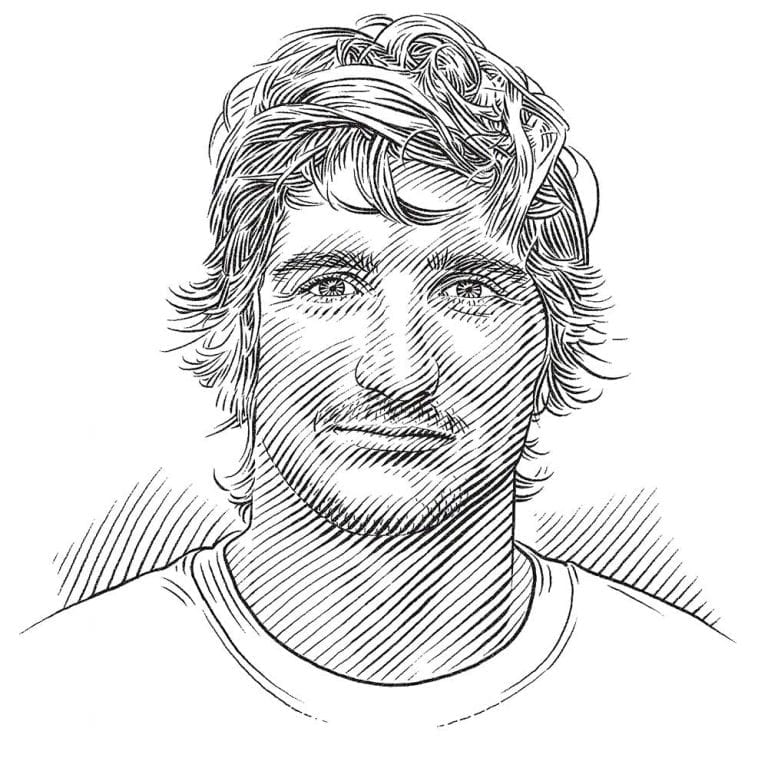

Samuel, better known as Doc, has been studying sharks for 50 years. He discovered how sharks see and even gave us insights into how they think. He founded the Bimini Biological Field Station in 1990, and has been training and inspiring young shark researchers ever since.