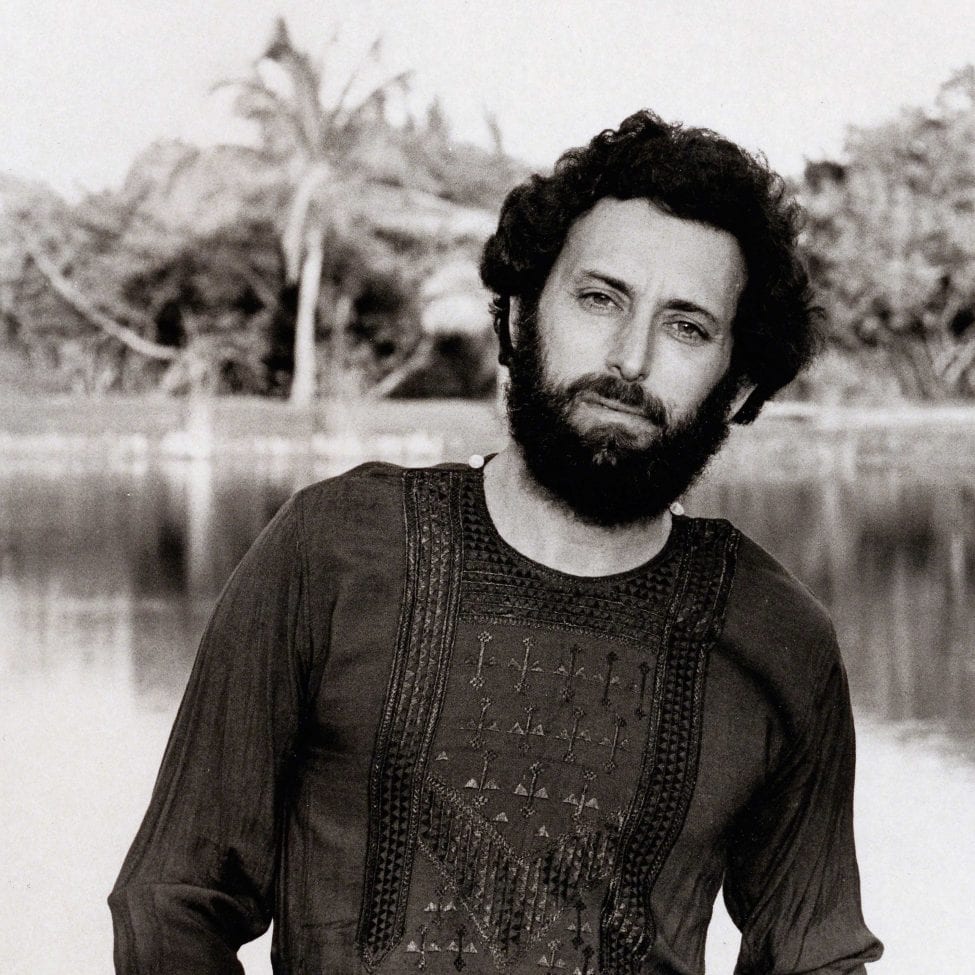

Eulogy of Dr Samuel H Gruber

A tribute to Doc

Dr Samuel H. Gruber

1938 – 2019

Dr Samuel (‘Sonny’) Harvey Gruber passed away at his home with his family by his side on Thursday, 18 April 2019 at the age of 80. A true pioneer and one of the most influential figures in shark science, Dr Gruber made contributions to elasmobranch research that cannot be overstated. Called simply ‘Doc’ by most who knew him, he broke new ground in the study of sensory physiology in sharks and over the course of a career lasting more than 50 years he published over 190 peer-reviewed papers on shark biology, ecology and behaviour, greatly advancing our understanding of these enigmatic creatures.

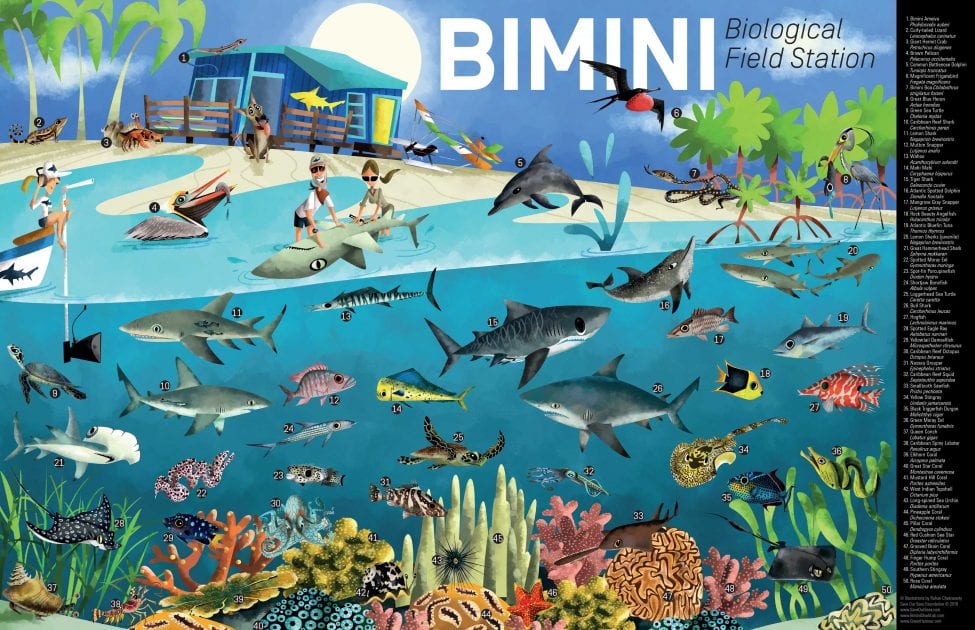

One of his greatest contributions to the field was the co-founding of the American Elasmobranch Society (AES) in 1983, along with California State University Long Beach professor Dr Don Nelson. The AES has become the largest professional society of elasmobranch scientists on the planet. Another major achievement, and the one that Doc was most proud of, was the establishment of the Bimini Biological Field Station (aka the ‘Shark Lab’) in 1990, which moved shark research forward through novel scientific findings and by serving as a conveyor belt of competent and passionate shark researchers.

Doc was born in 1938 in Brooklyn, New York, to Claire and Sidney Gruber. His love for the ocean and sense of connection to it emerged strongly when the family moved to South Beach in Miami, Florida, shortly after the end of the Second World War. He quickly became an avid swimmer and high board diver, feeling very at home in and under the water. Doc would have the family driver take him to the shore as often as possible, where he would spend hours at the beach or fishing docks, fascinated by the weird and wonderful creatures the boats would bring in at the end of the day. On one such day he was so enthralled by his surroundings that he left a brand-new pair of shoes on the dock. This was the final straw for his parents, whose patience was already strained by frequent instances of misbehaviour. They decided that enough was enough and in 1953 they sent him to military school.

Bimini Biological Field Station (BBFS)

Samuel, better known as Doc, has been studying sharks for 50 years. He discovered how sharks see and even gave us insights into how they think. He founded the Bimini Biological Field Station in 1990, and has been training and inspiring young shark researchers ever since.