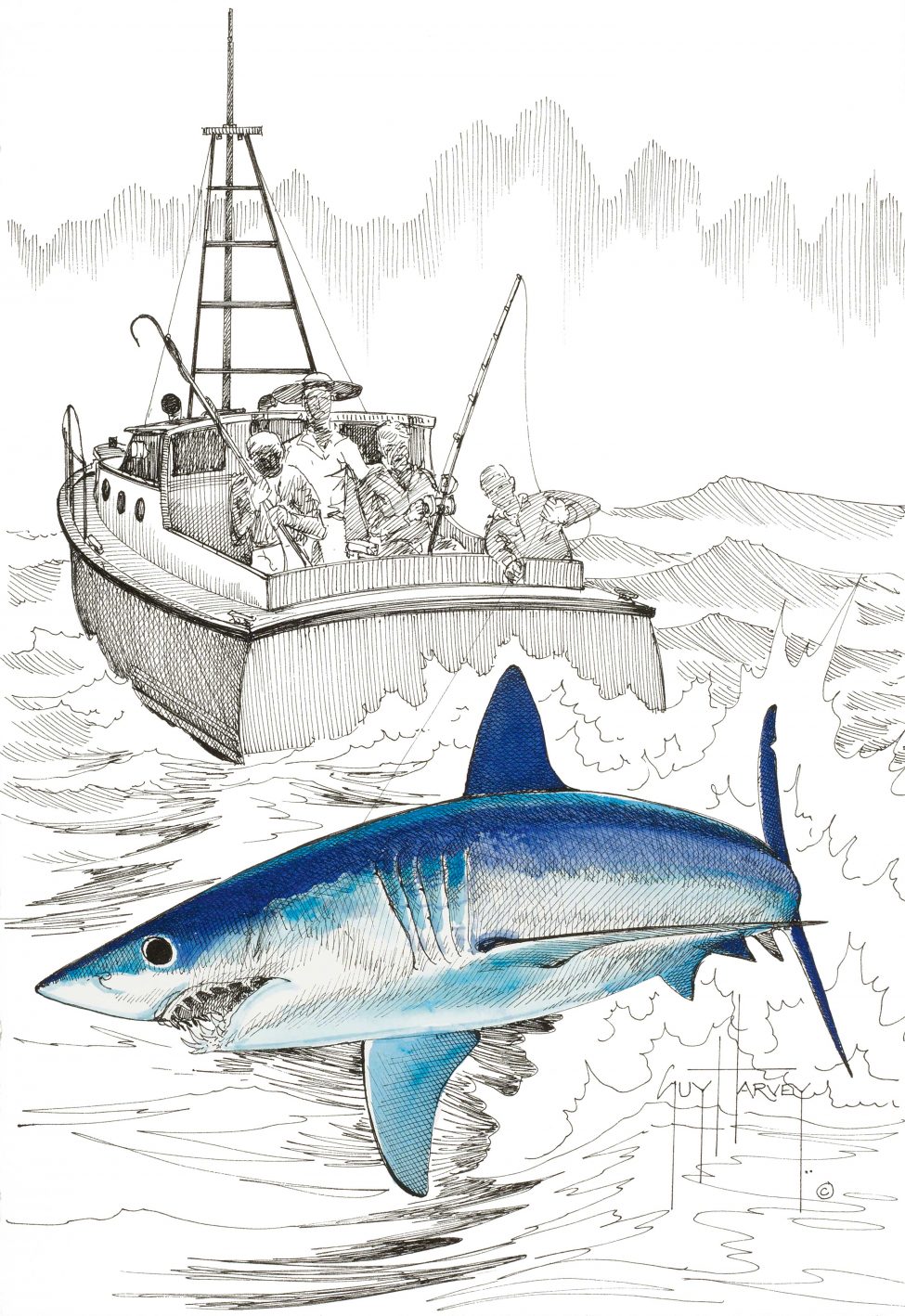

The shark loomed up. It was tired and stayed calm. It seemed large. A hundred and eighty pounds? All fish look bigger under water. Pay attention. There’s the leader. Unclip the harness. Here it is. Rod into holder. Leader in hand. Be smooth. Harpoon seems heavy; arm’s tired.

I had the weight of the fish on the leader in one hand, the weight of the long wooden harpoon shaft overhead. A man with a spear, face to face with a large, dangerous animal—an old, old scene.

I pressured the leader and the shark’s bullet of a snout rose through the surface, pointing at me. Bad angle. The hesitation made my tired arm weaken.

I relaxed the leader a little and the shark rotated slowly onto its side and turned to dive.

I struck and the fish exploded, spinning crazily and diving, ripping the dart from its side and stripping line from my humming reel.

I had not lunged hard enough; my arm was too tired from the fight and holding the heavy harpoon overhead.

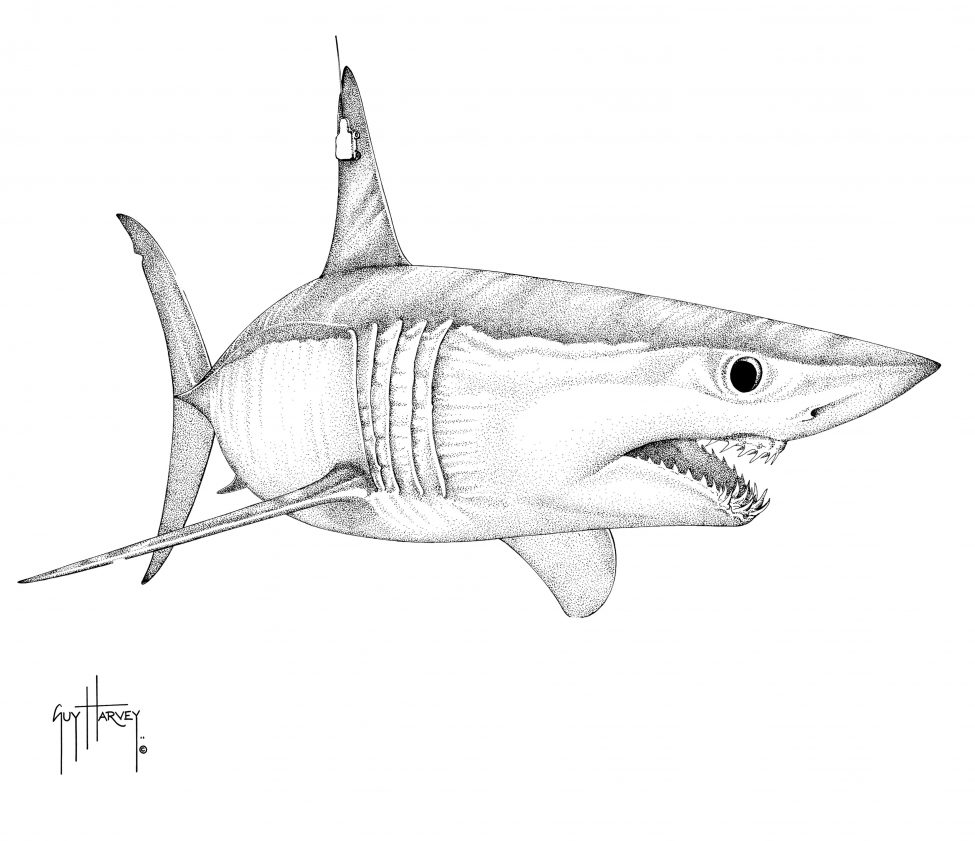

Amazingly, the violence did not break the line or throw a weakening kink into the leader. In a few minutes I again drew the shark close. I decided that this time I would try for a shot through the gills. A gill shot is more decisive, but riskier. The head, rather than the tail, comes up as you pull the harpoon line, making it harder to place the securing tail-rope, increasing the probability that the shark will bite and perhaps simply sever the harpoon line—and raising the possibility that a sudden leap will propel the animal straight at you.

The mako came up again. I was ready. But when the shark presented the perfect shot, I hesitated.

The shark waited.

I looked deep into that black eye. Undefiant, matter-of-factly, the mako informed me this was no game, not a “sport.” That eye rolled forward just a bit then back to me—and inquired what next.

I reconsidered, then thrust.

The mako blurred into lashing froth and blood. I reached for the gaff and sank it and swept him toward me and cinched the tail rope.

Now I had my prize. Each subsequent thrash pumped a new pillow of blood into the sea. For a few more minutes, the black eye queried: What next? Then the creature drained away into the sea, and all I had left was a dead carcass tied to the boat, and myself. And something had gone from me in that same billowing blood that took the shark and left the carcass. I’d sought to prove my place among others. The shark taught me that everything has its place, and I had overstepped mine. I knew then it was the last time I would ever feel that trembling buck-fever.

I had loved the sleek motion, the speed and agility, the gliding vitality and ocean-bursting power. And all these things, I had just destroyed. I had sought connection, but beyond connection, possession. And beyond possession, ego. That left my motives open to question. It is one thing to catch a fish and eat it. But there is in these equations a matter of scale, and such a thing as too much. And sometimes, why one does something is more important than what one does.

Now I’d have my steaks. Grills would sizzle. At the dock came the expected congratulations, the admiring onlookers male and female, the incredulous head-shakes that I had conquered this fish alone. My name found its way into the weekly fishing columns. I had distinguished myself. Perhaps people would say, “He’s a good fisherman.” But with sharks declining, I could not duck the fact that I was still drawing blood from such magnificent creatures. And that made the sought-after admiration feel hollow.

A few days later I repeated the offshore solo venture and located another mako. This time, after its leaping fight subsided and I drew the creature close, I leaned overboard not with harpoon but with hook remover. In those days virtually no one released sizable makos. But at the dock no one who asked what I’d caught questioned my tale of solo catch and solo release—because I’d proven my prowess with the earlier carcass. Now I was proving—if only to myself—that the next step in prowess was to relinquish the prize. But as it turned out, I again made the fishing columns, this time as a kind of mako liberator.

Neptune pronounced this good and did what he could to encourage the publicity; I caught seven makos that season—more than twice my previous seasonal high. And except for that first, I released them. Each release was duly noted in the weekly fishing news. People were responding favorably; some suggested that I was setting an example. Maybe I would become a good fisherman after all.

People are hungry to make their mark in the world. Every shark would understand. Or would they? The shark has a hunter’s attitude, but there’s nothing social in its killing. It gains only nutrition, knows no pride. The shark does only what it needs, and needs only what it does. Of the burden of needing to make an impression, the shark is free. Yet we cause the whole world, even the sharks of the blue ocean, to bear the burden of our ego. Certainly I had.

We must all kill to live, and scarcely a vegetarian would try denying it. Some measure of good resides in getting one’s food from nature, for the connections it brings, the sense of place and the community it gathers. But two forks exist in the decision tree: One is whether the killing is humane. The other, whether we can we keep doing this. Shark hunting fails both counts. If a course of action simply cannot last, we must admit to ourselves that it’s wrong. I knew that whether I killed one mako shark a year—or released them all—would not decide the future of the species. I wasn’t the problem, but we’re all always only part of the problem. At some point one confronts the question of right and wrong in private, with the door closed. We can do the right thing. Right things maintain a community. I prefer a community that includes, among many things, sharks.

We each make our solo voyages to deep, expansive waters. Alone in our contest with the wider world, we test our mettle and seek our trophies, promotions, compliments, and accolades. We strive to be needed and to thereby know there is a reason for us. We seek to be told we are good because we’re too unsure of ourselves to know. Yet often we remain so focused on our neediness that we forget the creatures—human and otherwise—we’re drawing into the vortex of our own passion play. All of us have compulsive loves we must forebear. We forget to see that we can engage the world without harming it. While we fish for approval, the challenge is to capture our prizes while bringing more to the world than we take.