Five years on track

Paul Cowley reflects on the progress of the Acoustic Tracking Array Platform that tracks animal movements between Cape Town’s False Bay and Ponta do Oura in Mozambique.

Many marine species have suffered significant population declines in recent years, due mainly to humans’ insatiable demands for food. Conservation and management efforts need to keep abreast of these declines to ensure the sustainability of species that are of ecological significance, economic value or conservation concern. In most cases, the effective conservation of such species relies on an improved understanding of their patterns of habitat use and their movements and migrations.

The quest for such information by scientists and resource managers has been empowered by advances in aquatic animal tagging and tracking technologies, particularly in the form of acoustic telemetry networks. The Acoustic Tracking Array Platform (ATAP) is one of many global examples of how researchers can gather multiple-year data with high spatial and temporal resolution on animals tagged with long-life acoustic transmitters. The ATAP array off the southern tip of Africa comprises an extended network of moored acoustic receivers spanning approximately 2,200 kilometres (1,370 miles) of coastline from False Bay, near Cape Town in South Africa, to Ponta do Oura in Mozambique.

The southern African coastline is largely exposed and has few large bays, but is well endowed with estuarine inlets. Besides being a global biodiversity hotspot, the region hosts the greatest marine migration on the planet in the form of the annual sardine run. Dubbed ‘the greatest shoal on earth’, this migration of small pelagic fishes, often in shoals up to 10 kilometres (six miles) long, is pursued by a host of apex predators, including sharks, birds, dolphins and numerous predatory fish species. Collectively, these geographical and biological features make southern Africa a perfect natural laboratory in which to study the movement behaviour and migration biology of marine animals.

ATAP first gained momentum as a marine science platform when the Canada-based Ocean Tracking Network (OTN) project expressed an interest in lending acoustic telemetry hardware to interested partner countries around the globe. Researchers based at the South African Institute of Aquatic Biodiversity (SAIAB) who were already conducting acoustic telemetry studies recognised the benefits of creating a nationwide receiver network. They started drafting proposals and canvassing support to establish one. The greatest challenges at that stage were to secure a shared vision and develop an ethos of open-access data sharing within the research community. This was achieved by setting up a national research co-ordinating unit called the Biotelemetry Research Group. SAIAB then entered into an agreement with OTN and the securing of telemetry hardware through this partnership and additional hardware support from the National Research Foundation (NRF) led to the birth of ATAP five years ago.

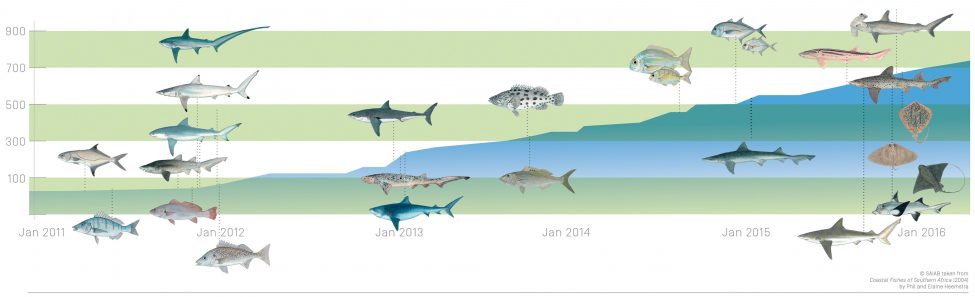

Since its inauguration in August 2011, ATAP has continued to grow in terms of the number of species and number of individual marine animals tagged. To date, more than 700 individuals representing 27 species and 20 families have been tagged with acoustic transmitters. Current research focuses on large predatory sharks and important coastal fishery species. Prominent elasmobranch species include white sharks Carcharodon carcharias, sevengill cow-sharks Notorynchus cepedianus, bull sharks Carcharhinus leucas and ragged-tooth sharks Carcharias taurus, while prominent teleosts include leervis Lichia amia, spotted grunter Pomadasys commersonnii and dusky kob Argyrosomus japonicus. The ATAP management team, based at SAIAB in Grahamstown, services the deployed receivers at six- to eight-month intervals and all the downloaded data are stored on a local database. Upon receipt of a data request, SAIAB collates the information gathered on a tagged animal and sends it to the tag owner. Currently more than 20 researchers and students from 14 different organisations benefit from this data-sharing arrangement.

The Acoustic Tracking Array Platform (ATAP)

The ATAP covers thousands of kilometres of the Southern African coast. Scientists are able to use this collaborative array to paint a picture of how fish and shark species behave along the coastline to better manage and protect them in the future.