Hidden Mortality: The effects of by-catch

Fisheries come in a number of different guises, but tagging along with virtually all of them is a simple word with portentous significance: by-catch. Dr Dean Grubbs weighs up the world’s fisheries and explains why some are better for elasmobranchs than others.

Photo by Brian J. Skerry | National Geographic Creative

What is by-catch

By-catch is one of the most difficult issues to overcome in fisheries management. In simple terms, it is the capture of animals that are not part of the targeted or desired catch. Often these animals are not marketed but are discarded at sea, either alive or dead. In many fisheries, by-catch at some level is unavoidable and sometimes it may even be sustainable: for example, if the by-catch rate is negligible, if the by-catch species reproduce and replace themselves at a faster rate than the targeted catch, or if most of the by-catch is released alive and subsequently survives.

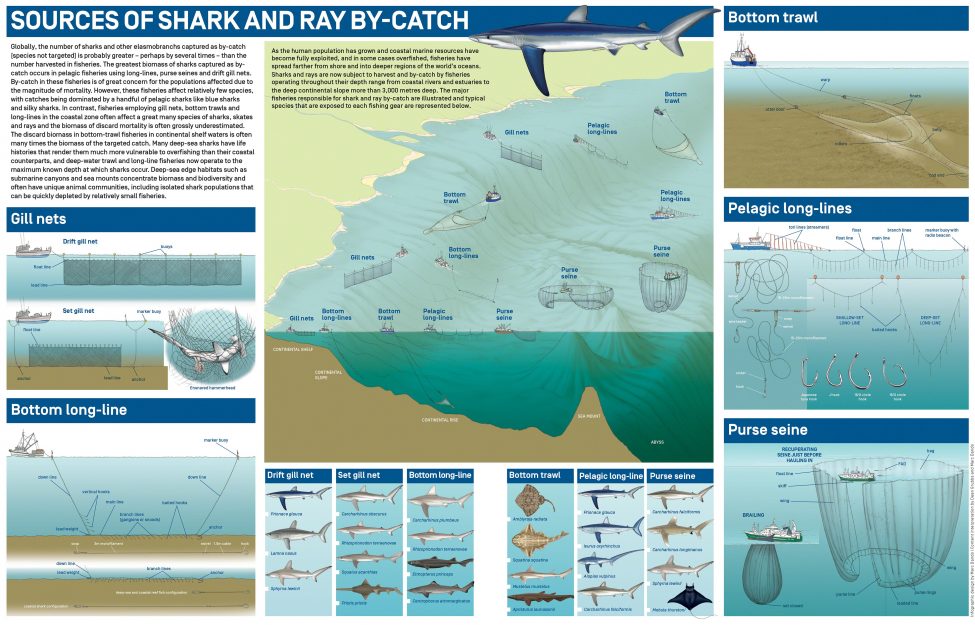

A simple metric often used to evaluate how ‘clean’ a fishery is in terms of by-catch is the ratio of discards to landings. In a perfectly clean fishery, only targeted species of marketable size would be captured and this ratio would be 0 since there are no discards. Purse-seine fisheries that target small schooling fishes such as anchovies and menhaden tend to be the cleanest fisheries. Targeted species often make up about 99% of the catch (a discard-to-landings ratio of 0.01) because they are found in massive single-species schools. However, it is important to realise that these are among the largest fisheries in the world, so even a small proportion of by-catch can add up to millions of metric tons of discards on a global scale. It is also important to recognise that purse-seine fisheries may have other ecological consequences, since they target the forage base (the food species for other species) for larger fishes, including sharks.

At the other end of the by-catch spectrum, bottom trawls for shrimp and demersal (bottom-associated) fishes are typically the ‘dirtiest’ fisheries. For example, the dead discards in shrimp trawl fisheries are usually larger, sometimes much larger, than the targeted catch. It has been estimated that in the Gulf of Mexico between five and 10 kilograms (11 and 22 pounds) of by-caught fish, crabs and other animals are discarded for every single kilogram (2.2 pounds) of shrimp.

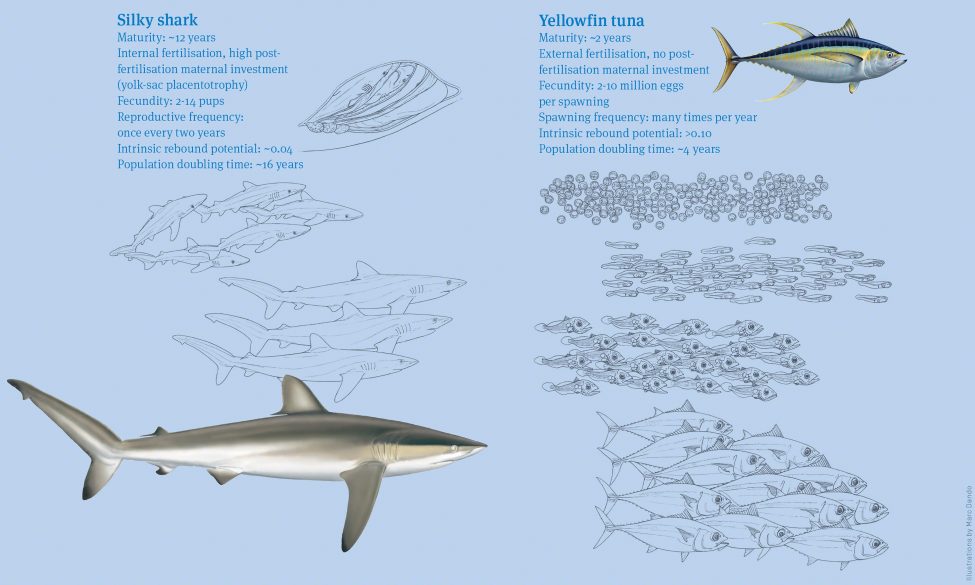

By-catch is especially problematic when the incidentally caught species has a life history that is much more conservative than that of the targeted catch; in other words, it matures later and reproduces more slowly. If the targeted species matures quickly and can double its population in one or two years, even a small by-catch of a long-lived species that requires more than a decade to double its population may be unsustainable.

An endangered or charismatic species, such as a marine mammal or sea turtle, being taken as by-catch often elicits an emotional response from the general public. Of greater concern, though, is the fact that these species are often long-lived and reproduce slowly, so their populations do not rebound quickly after they have been depleted. For example, sawfishes (Pristidae) are considered to be the most imperilled of all chondrichthyans (sharks, rays and chimaeras). All five sawfish species are Endangered or Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; in the USA, the smalltooth sawfish was the first native marine fish to be listed as Endangered under the US Endangered Species Act. Yet even though this species is thus fully protected in US waters, it is caught incidentally in shrimp trawls – and this fishery is believed to be the main reason for smalltooth sawfish mortality. Whereas the targeted shrimp mature in less than a year and produce hundreds of thousands of offspring – thus replacing themselves many times in one year – the smalltooth sawfish takes about 10 years to mature and produces about 10 offspring probably every other year, which means that only 10–15% of the popuulation is replaced each year. Such disparate life histories of targeted and by-catch species within a fishery are a recipe for trouble.

The equipment fisheries use to catch fish can be divided into two broad categories: active gear, which physically moves through the marine environment and is capable of catching animals regardless of their behaviour; and passive gear, which requires the quarry to come to it. Active gear includes purse- and haul-seine nets that encircle schools of fish; mid-water trawl nets that are dragged through the water column and essentially filter out the animals in it; and bottom-trawl nets and dredges that scrape animals off the sea floor, often causing significant damage to the habitat.

Passive gear may either attract fish, often with bait, or simply catch fish that pass by. In the first category are included a baited hook on a line and baited pelagic and bottom long-lines, as well as traps that attract fish by providing food or refuge. Nets are the other form of passive gear and they include gill, pound and fyke nets. Gill nets may be set on the bottom or in mid-water and may be anchored or drifting.

On a global scale, purse-seine and trawl fisheries yield far more marine produce than all other types of fishing gear combined. Rates of by-catch, which includes sharks and other elasmobranchs, vary dramatically between these fisheries; even small operations can be of concern in some circumstances. There are four major fishery types – trawling, gill-netting, long-lining and purse-seining – and each involves elasmobranch by-catch in different ways.