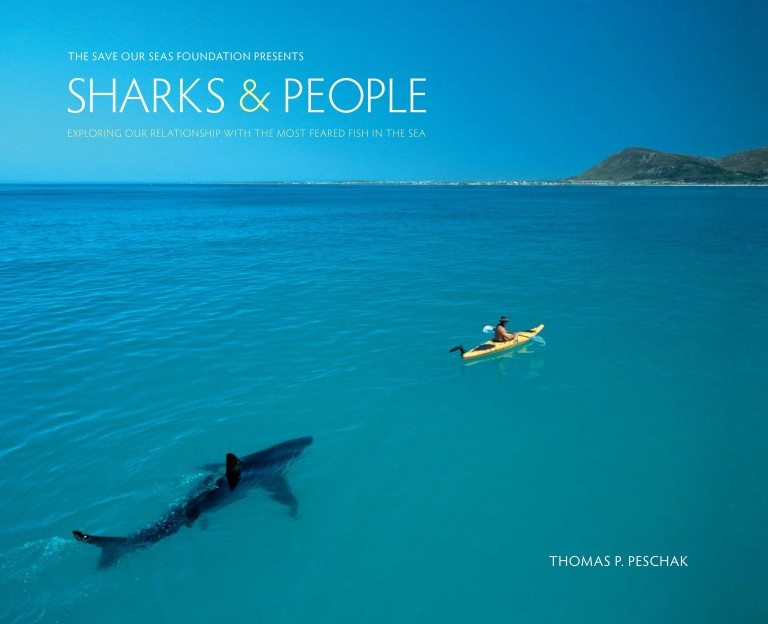

What message are you trying to communicate through the book?

The subject of sharks is often polarising. Sharks are different things to different people. I have spent as much time with shark fishermen as I have with conservationists. I have spent time with surfers who are afraid of sharks and with divers who seek them out. I have tried to surround myself with as many different perspectives as possible. I am hoping the book will widen perspectives and create conversations. It is not pro shark or pro people. I am not under any illusions that this book is a panacea, but I hope at the very least it will contribute to more constructive dialogues about how people and sharks and people can co-exist.

In your book you describe witnessing the aftermath of a shark bite. How do you feel these incidents need to be approached?

Communities that have experienced shark bites are traumatised. As conservationists we are all guilty of rattling off statistics about death by toaster, lightning or falling coconuts without considering the small percentage of people directly affected. Don’t get me wrong, shark attacks are exceedingly rare, but they do happen. We have to take each occurrence seriously and treat those affected with sensitivity and compassion.

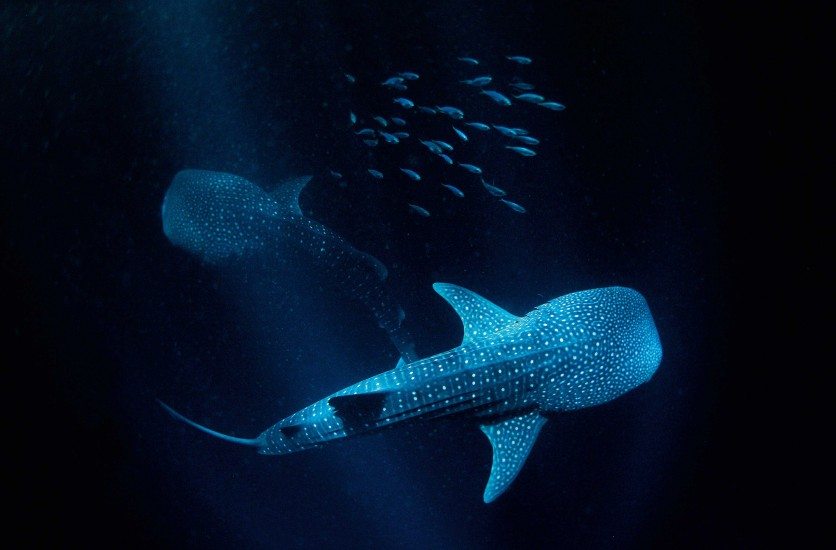

In one of your earlier books you were outspoken against all shark fishing. Is this still true?

It is incredibly difficult to create and measure the environmental sustainability of shark fisheries, albeit a few well-managed fisheries do exist. I think my biggest change of heart has come from interacting with fishermen in developing countries. In the past, I saw them as faceless negatives, responsible for the destruction of a species and environment that I treasure. Today I recognise that fishing is a critical livelihood for millions of people, many of whom are living far below the poverty line. Sharks are often a way of increasing the value of their catch. Putting shark fins on someone else’s table ultimately means putting food on their own table. Shark meat is an economical source of protein for the poorest of the poor. In these communities, shark finning (cutting off the fins at sea and discarding the body) is not widespread because the meat is a staple. If shark fishing is banned all together, many communities could become even more desperate. Ultimately, a living shark has much more value than a dead one. But the process of transforming a fishing community into an ecotourism community is complex. In the end, this change has to come from inside the community in a way that is contextual and self-sustaining.