Losing the taste for Shark Fin soup

SOSF principal scientist Sarah Fowler reviews what the SOSF has been doing to address the global threat to sharks and the extent to which its efforts are making a difference.

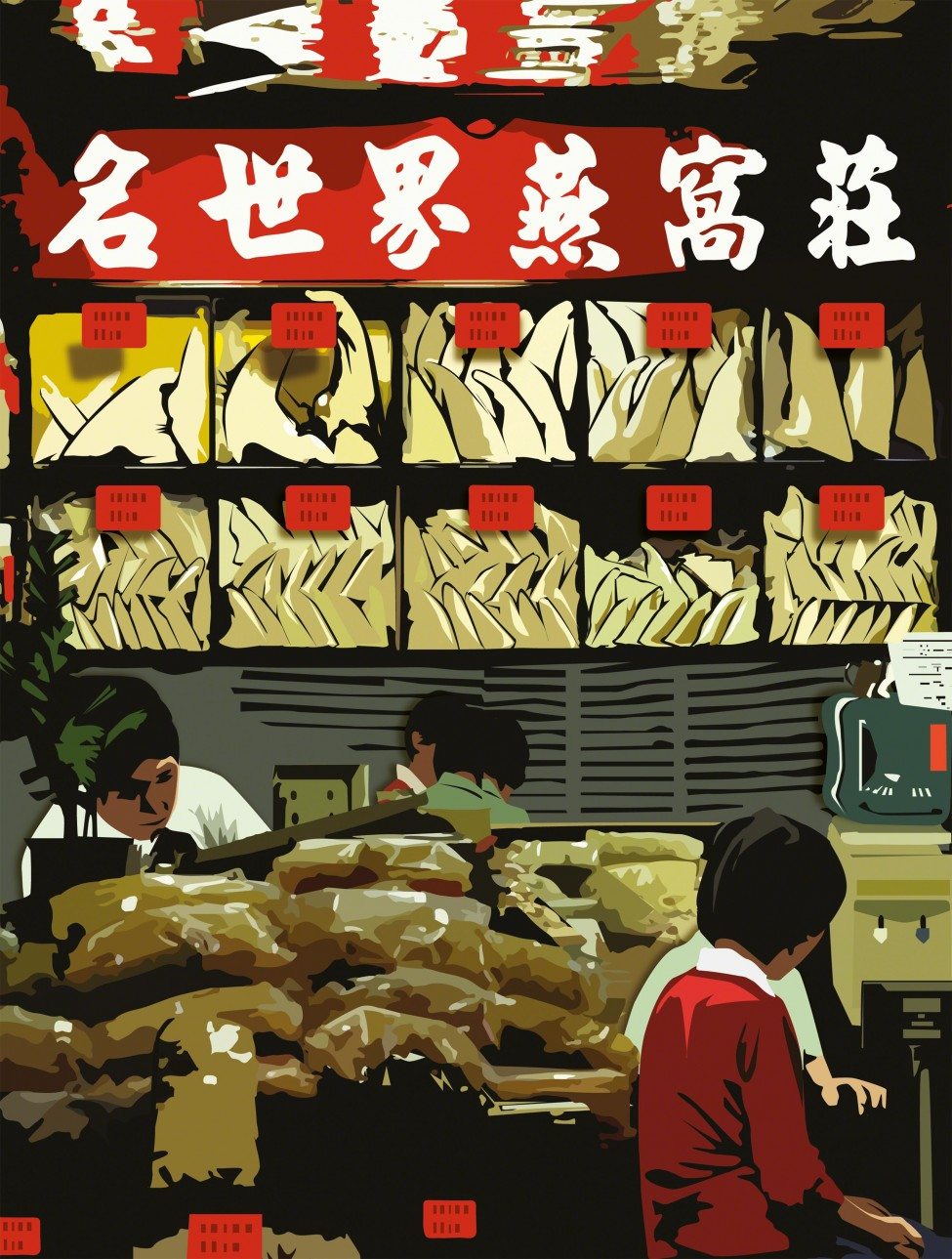

Photo by Thomas P. Peschak | Artwork by Alessandro Bonora

Demand for shark fin, to supply the huge market demand for an East Asian luxury soup, has driven most unsustainable shark fisheries since the early 1990s. Of the shark species identified in Hong Kong’s shark fin markets, 70 percent were pelagic sharks. Worryingly, more than 80 percent of the pelagic sharks that are commonly caught in high seas fisheries and harvested for their fins or meat are so seriously depleted by fishing pressure that they have been assessed as Threatened or Near Threatened in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Many other coastal and deep-sea sharks that enter international trade are also assessed as having a higher risk of extinction.

The Save Our Seas Foundation has, almost since its inception, supported projects aimed at reducing the impact of the international shark fin trade. These have addressed several key aspects of this threat, including:

- improving legislation and shark fisheries management to prevent shark finning and over-fishing, and enforcing finning prohibitions effectively,

- raising scientific knowledge and public awareness and providing technical advice in support of the designation of one of the world’s largest shark sanctuaries,

- developing novel techniques for monitoring trade by identifying fins in landings and markets, and reducing demand in the major consumer markets through education and awareness campaigns.

Other organisations have focused upon air and sea freight transport networks, seeking to hinder the trade by persuading carriers to stop moving shark fins to major processing centres and end markets. Several airlines, for example, no longer carry shark fin as freight or serve it to passengers, and the Evergreen Line (which operates the world’s fourth largest container fleet) has stopped shipping shark fin.

Recent media accounts of falling shark fin prices around the world, reportedly driven by a declining consumer market in China (the world’s largest consumer of shark fin products), have been presented as evidence that campaigns to reduce the consumption of shark fin soup, and hence overall mortality due to shark finning, have succeeded. So too, have reports of decreased imports and consumption of shark fin soup in China. Can this be true: is the work of the SOSF, its partners and other conservation bodies having the desired effect? If so, which stages in the supply chain are being addressed most effectively? Can we now even afford to relax our efforts?