The Old Man and the Sea

A frequent visitor to the docks of Kesennuma, Japan’s busiest landing port for sharks, Mareike Dornhege recognises the value of learning from Japanese fishermen, the veterans of the Pacific shark fishery.

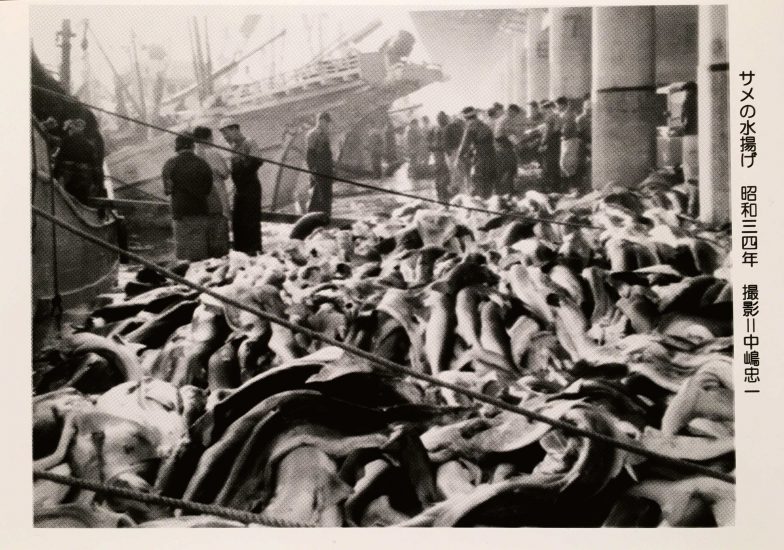

Photo by Tadakazu Nakajima | Rias Ark Museum of Art

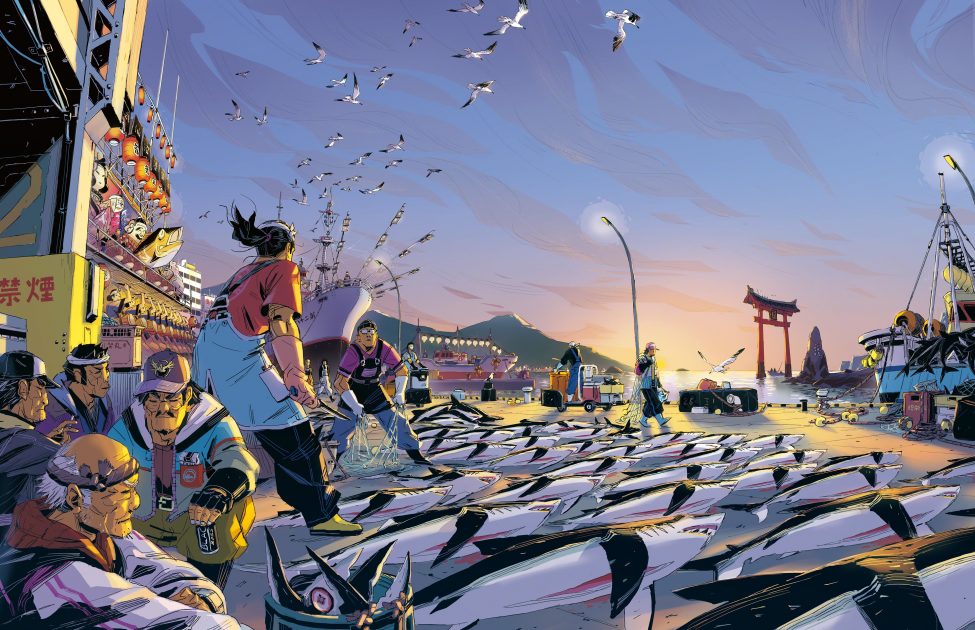

I am hopping from one leg to the other, rubbing my palms in a futile attempt to warm them. It is 4 am on a cold January morning on the Pacific coast of northern Japan and I am standing on the dock at Kesennuma. Japan is currently the globe’s 10th biggest shark-fishing nation and Kesennuma is responsible for about 80% of the landings. I am watching a 30-ton drift-net vessel unload its catch of dozens of salmon sharks. Crows and seagulls circle overhead as port workers lay out the sharks’ bodies in neat rows on the brightly lit dock. At the far end, longfin mako, shortfin mako, hammerhead and a few thresher sharks are on display for potential buyers, next to large piles of hundreds of blue sharks. It is this species that makes up about 80% of the landings.

It is a noisy and busy place and the port worker at my side is concerned that I might slip on one of the puddles of frozen water and blood, or perhaps collide with one of the many forklifts scooting quickly back and forth behind me. I smile at the captain of a salmon shark vessel who is cleaning up on deck and remark on how neat his wooden-decked boat looks. Eagerly he begins to tell me of his four-day fishing trip to the northern tip of the main island of Japan in search of salmon sharks. The trip was clearly successful, as I watch his small crew unloading more large adult salmon sharks from the hold, lifting them by the tail fin one by one with a rope and crane, careful not to sever their still-whole bodies.

‘How do you know where to find them?’ I ask. In the thick accent of northern Japan, he explains to me that sharks ‘ride the currents’ and he has learnt to follow their seasonal migration over the years. For a moment I forget about the noise, the cold and the wind as I absorb first-hand knowledge about the behavioural ecology of salmon sharks. I am fascinated by his detailed understanding of their movement patterns and sexual and age disparity. Contemplating that visits such as this might prove even more interesting than I have envisaged, I follow a member of the port staff to see the operations of the dock’s central office.

Gladly I accept a hot coffee from a young dock worker as we take our places for a run-down into the workings of a fishing dock that on most weekdays handles several tons of fish, including tuna, bonito, billfish, sharks and Pacific saury, not to mention catches of coastal delicacies such as seaweeds and even sea squirts. Many of the other staff members eye me suspiciously. Few women work here and those that do are definitely not foreigners. I realise that I will have to break down a few barriers. This is my third visit already and only now am I finally allowed to conduct interviews.

’We’ve had bad experiences,’ explains one of them with a shrug. Western journalists came, took photographs of their shark catch and sold them to newspapers for sensational stories telling how Kesennuma fishermen ruthlessly hunt sharks to extinction. Although media coverage about the dire need to conserve sharks is vitally important to inform the wider public of our work, such reports that include no scientific background or statements from the local community can do more harm than good. In the worst-case scenario, they harden the front between fishermen and scientists or NGO workers, hampering progress on sustainable fisheries management.

The fisheries cooperatives in a few ports arrange for me to meet some retired long-line fishermen. Most are in their 80s and, having started fishing in the 1960s, they have decades of experience. A few active fishermen in their 40s join us. The fishermen explain their gear and methods in great detail and one even goes to fetch some equipment to show me.