West Africa

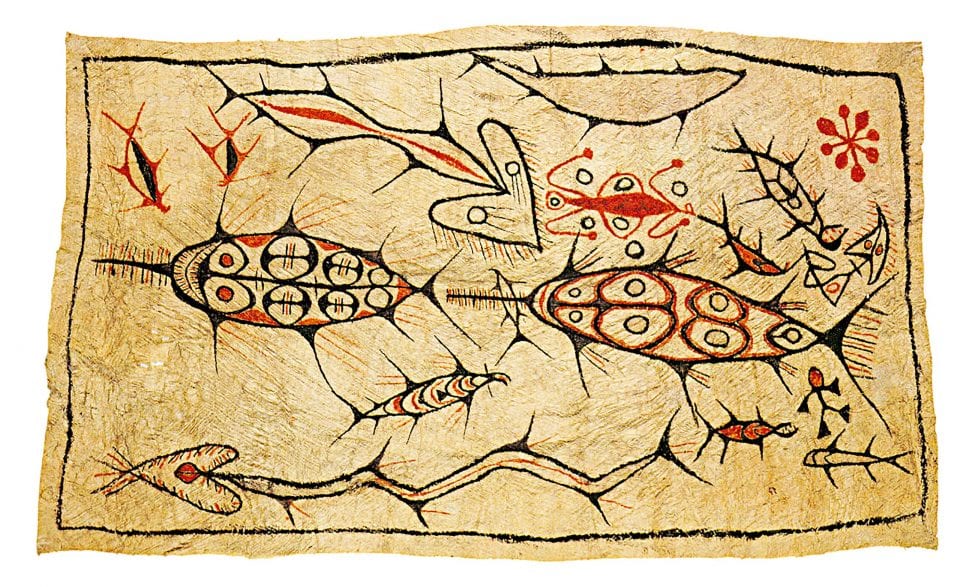

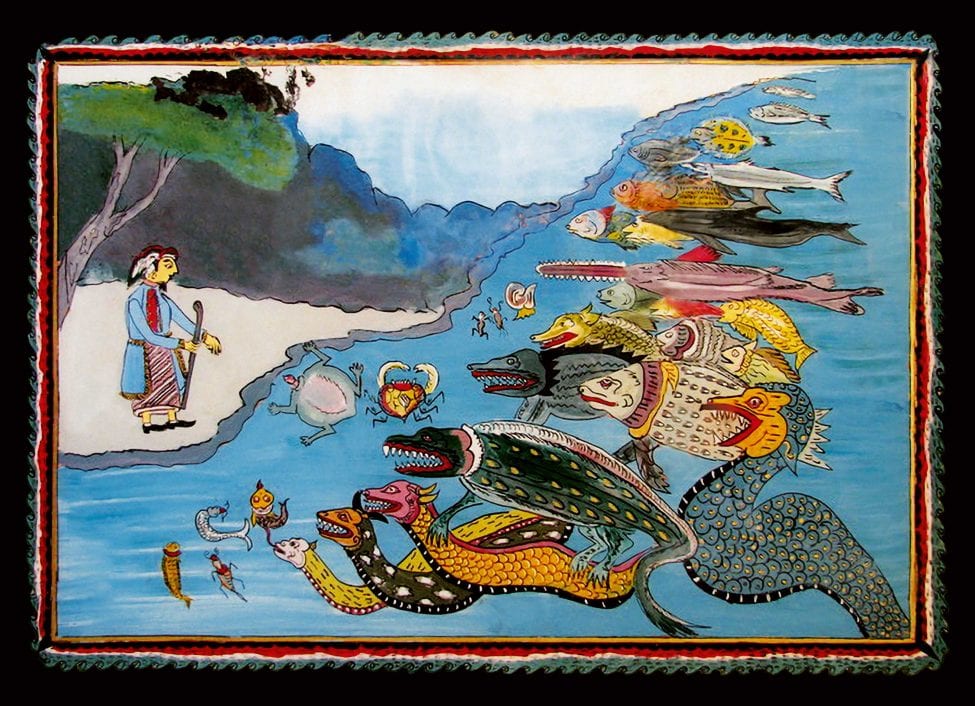

West Africa’s only archipelago, the Bijagos Islands of GuineaBissau, harbours a unique culture that has remained relatively intact, thanks to limited transport options from the mainland. On these islands football shirts, miniskirts and flip-flops may now be favoured over grass skirts, but the people still hold their animist beliefs, perform ceremonies and traditional dances and attach special significance to creatures such as the hammerhead shark and the sawfish.

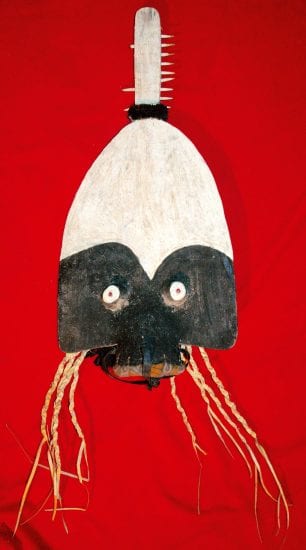

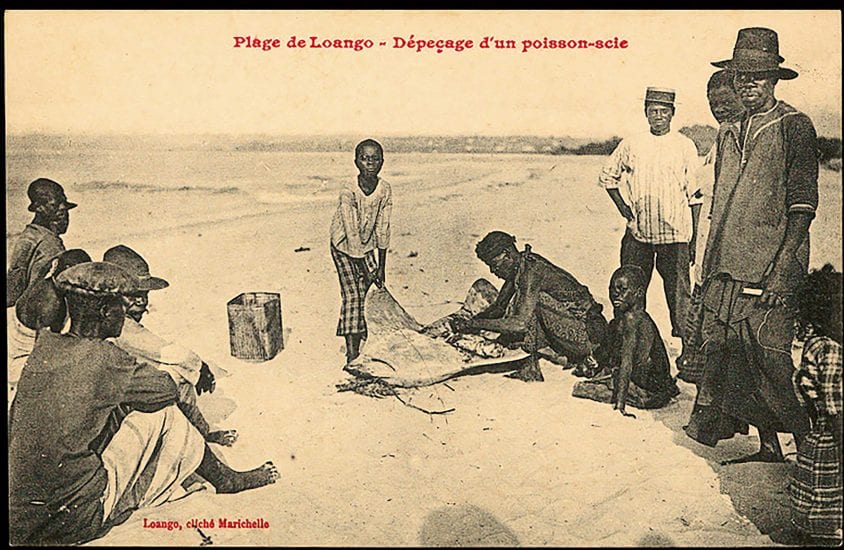

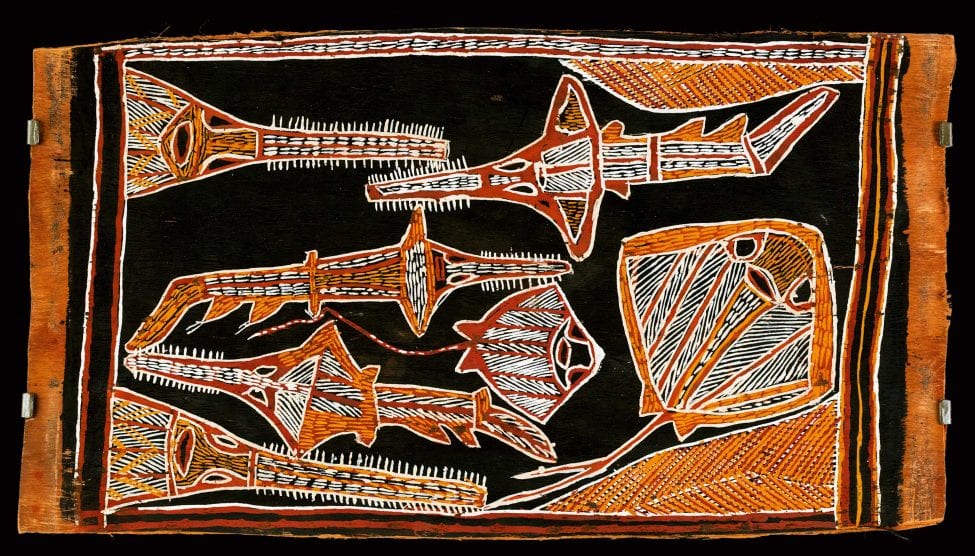

The culture of the Bijogo people includes numerous ceremonies to mark important life stages and events for the islanders. As part of the ceremony for male circumcision, sawfish were caught and brought to the village elders as an offering or sign of respect. In ceremonial dances, men used to wear headdresses topped with the saw of a small sawfish and perform a dance mimicking the sawfish’s movements – motions the young initiates reportedly learned while hunting from wooden fishing platforms, below which they could observe sawfishes feeding. Nowadays, sawfish rostra (saws) are so difficult to find that the great triangular headdresses bear carved wooden representations of saws instead of the real thing.

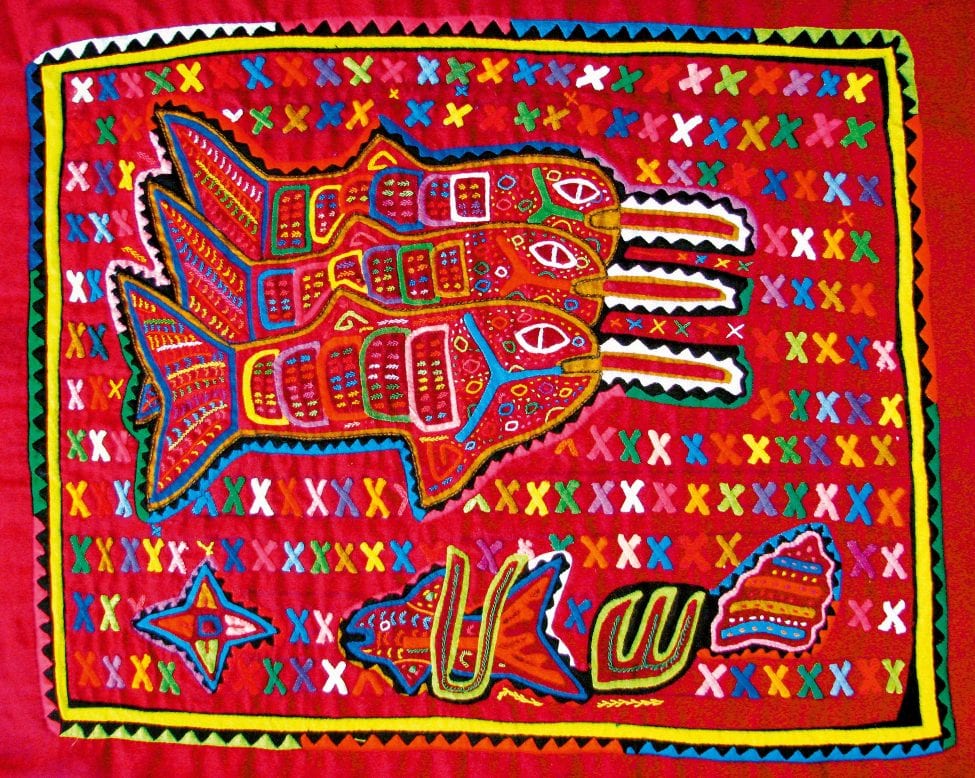

‘When a sawfish attacks another fish, the victim never escapes.’ Akan proverb | Ghana

The Akan people of western Ghana are renowned for making a strong connection between visual and verbal expressions and for how they blend art and philosophy. Proverbs and sayings featured prominently in their culture and had political, economic and social significance. The many beautiful weights they made from 1400 AD onwards were used as counter-weights for measuring out gold dust (their traditional currency until replaced by coins and paper money). These weights, made from brass, often had forms that were linked to specific proverbs.

The sawfish was sacred to the Akan people, symbolising individuals who held power in coastal communities. The proverb associated with the weight depicting a sawfish is ‘When a sawfish attacks another fish, the victim never escapes’. This was meant to convey the indisputable authority of the king. More generally, fishes symbolised abundance in West African cultures. The sawfish symbol, which linked prosperity and leadership, was so important for Akan societies that the West African Monetary Union chose it, in the stylised form of the sawfish weight, to adorn all the coins and notes of the West African franc (the currency of Senegal, Guinea-Bissau and Guinea-Conakry).

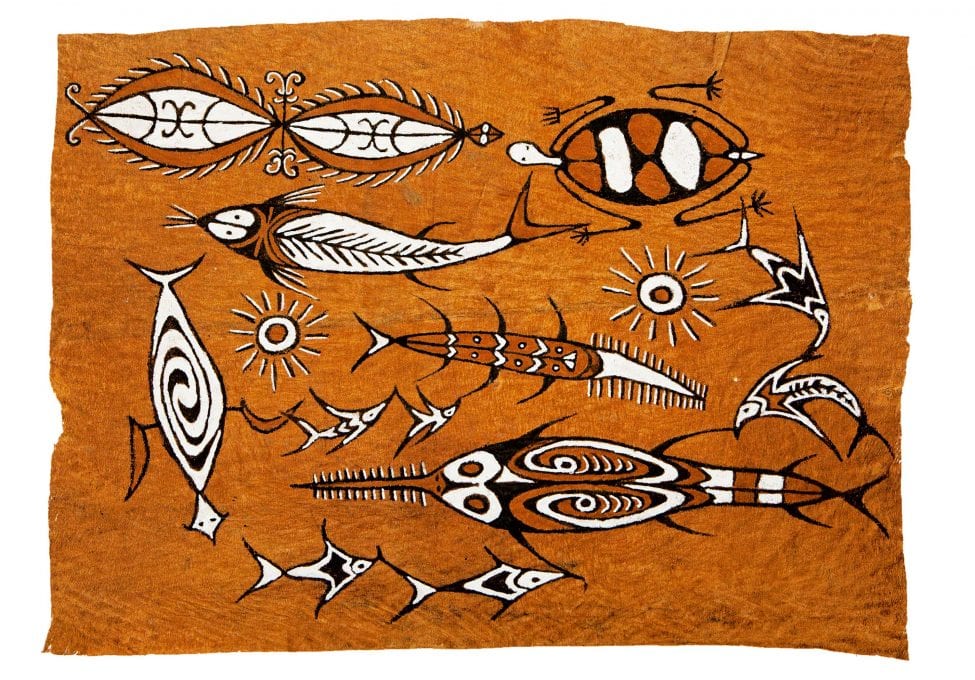

Around the Volta Estuary in eastern Ghana, the Ewe people revered sawfishes as spiritually powerful entities, classed as tro, of a divinity between humans and God. The Ewe had formal sawfish propitiation rites to dispel the danger presented when a sawfish became entangled in a fishing net. The powerful spirit was appeased with offerings of corn meal, alcohol and palm oil. If this ceremony was not performed, fishers who caught sawfishes were believed to have bad luck – illness might strike them or one of their family members, or they might be involved in accidents, for example.