Science at the far end of the world

Dubbed ‘the navel of the world’, Easter Island in the South Pacific is as much a place of startling marine biodiversity as it is of eyebrow-raising mythology. However, little marine research has been done before now, and establishing a baseline of data to inform future conservation management in this part of the world is no mean feat. Lauren De Vos speaks to SOSF project leader Naiti Morales Serrano about the challenges and triumphs of starting science in far-flung places.

Photo by James P Blair | National Geographic Creative

Whitewash broils in an angry sea, building momentum before dashing itself against the island. Few have set foot here before; the only hint of human presence is a lighthouse that blinks forlornly at the night sky. The allure of an ecosystem both unexplored and unexploited is like the promise of a new land that guided the first Polynesian navigators to this region: magnetic.

Waves pulverise volcanic rocks, jagged teeth bared to the sky. A boat-load of researchers judge their approach. Spying a gap in the incessant pounding, the skipper gives the throttle rein and the boat shoots forward. The scientists and camera crew prepare to leap ashore. Water starts to heave back up the sides of the island, sucking the boat perilously close to the rocks. Timing is critical. The skipper must get close to the island to allow disembarkation without beaching their craft. As they backpedal, the motors growl in opposition to the pull of the water. In a nimble nanosecond, scientist Enric Sala leaps safely onto the island of Salas y Gómez.

Few people would find in this scene from the documentary The Lost Sharks of Easter Island the inspiration to start their PhD. Doing so would require that they cast aside serious misgivings about the isolation and challenges. But in Naiti Morales Serrano it sparked an idea. In the film, scientists Enric Sala, Carlos Gaymer and Alan Friedlander explore Easter Island and neighbouring Isla Salas y Gómez. Their mission? To highlight the region’s biodiversity and muster support to address its challenges.

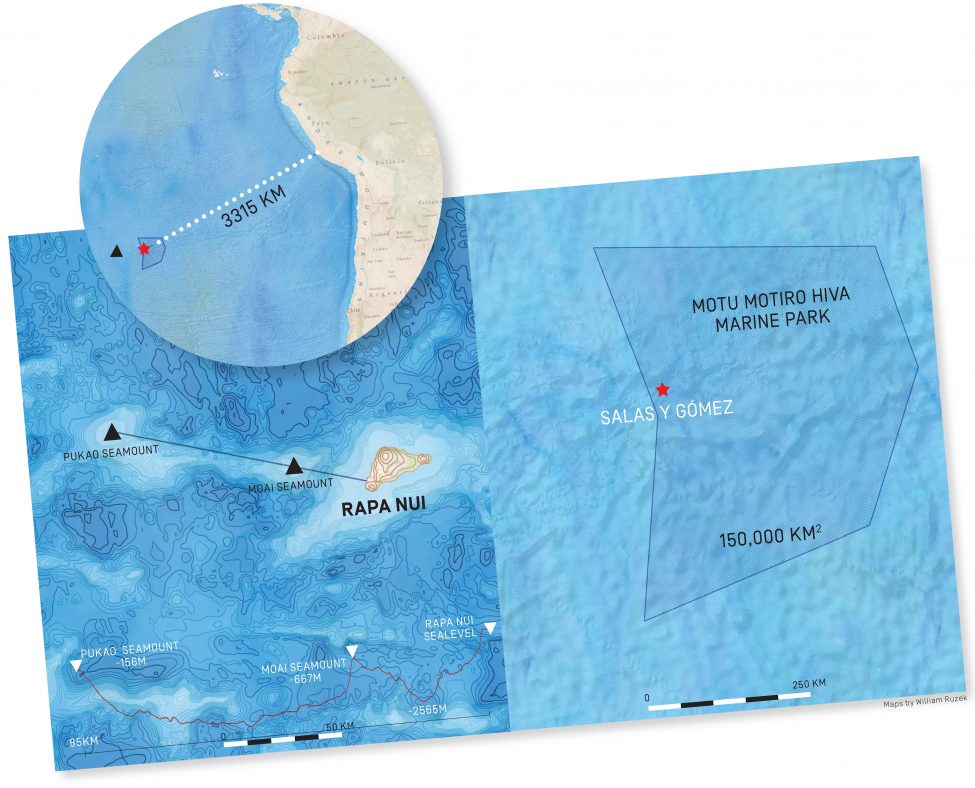

‘I saw that and I thought “Okay, I want to work there!”’ recalls Naiti. After graduating with a degree in marine biology, she had already worked at various jobs to nurture her passion for sharks. ‘I worked with kids too, teaching them about sharks, and that was really cool!’ She sought out Carlos, convincing him to take her on as a student. ‘I said, I know you don’t work with sharks, but I really want to do this, and I saw this documentary…’ she pauses, ‘and I have some ideas, so … can I work with you?’ Now a PhD candidate based at the Universidad Católica del Norte in Chile, she is one of those rare people who find meaning in taking up a challenge. Easter Island, or Rapa Nui by its local name, is the most remote inhabited island in the world. Flung 3,700 kilometres west of the Chilean mainland into the Pacific Ocean, it is the easternmost of the Polynesian islands and forms part of what scientists call the Easter Island Ecoregion. Salas y Gómez, known locally as Motu Motiro Hiva, is its uninhabited island neighbour 400 kilometres to the east. Two rocks standing sentinel in a vast sea, Motu Motiro Hiva has a combined area of a mere 0.15 square kilometres.

The whole Easter Island region has a volatile history, both geologically and anthropologically. Volcanic activity, thanks to the Easter Hotspot that boils deep below, gave birth to the islands and sea mounts that characterise this area. The sea mounts are essentially underwater mountains that range in age from 8.4 million to 13.1 million years, forming the Easter Sea Mount Chain and stretching eastwards from Rapa Nui for nearly 2,000 kilometres. Both Rapa Nui and Motu Motiro Hiva are considered geological youngsters, their youthful 0.8 million years recent history compared to volcanic elders like the Hawaiian islands.

‘I’m trying to figure out how things work for top predators around Easter Island,’ Naiti begins. The island is a territory of Chile, and a projection by that nation’s Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas put the population of Rapa Nui at an estimated 6,600 people in 2016. Although there is a tradition of harvesting from local waters, there is currently no formal spatial protection for marine life around the island. However, in 2010 the Chilean government declared the waters around neighbouring Motu Motiro Hiva a marine protected area, with an extent of 150,000 square kilometres.

‘My thesis looks at how top predators relate to these two areas,’ explains Naiti. She wants to find out which predators are found around Rapa Nui, and to do so she deploys Baited Remote Underwater Video Systems (BRUVs) to assess their abundance and diversity. She is also exploring how these populations are connected between the two islands. ‘For that, I’m doing genetics and tracking with satellite tags. I’m going to be using stable isotopes as well,’ she elaborates. In effect, her project is a bid to tease out complex relationships in an ecosystem where top predators are both important and of conservation concern.