The Oldest on Earth?

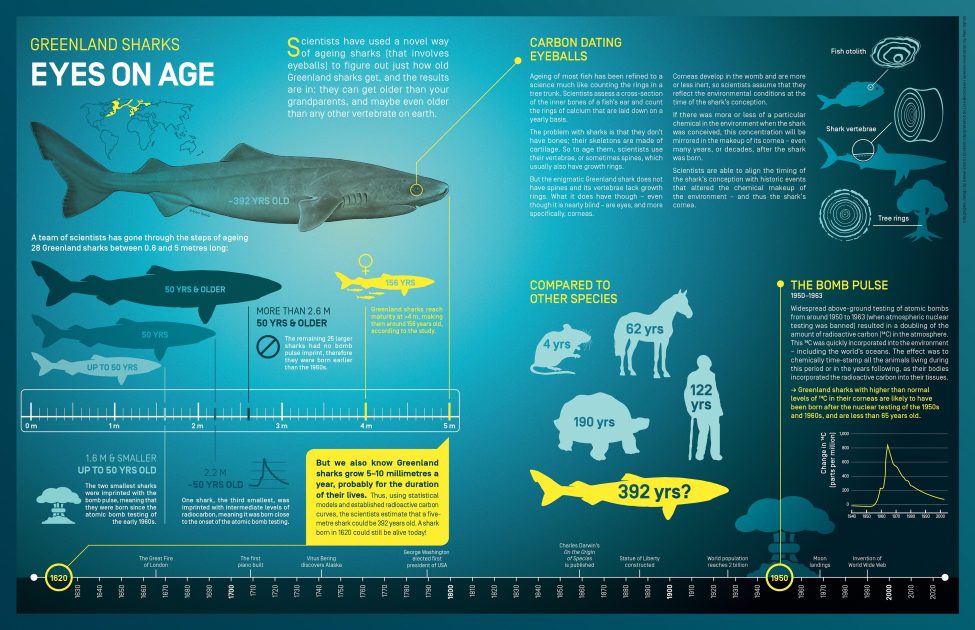

We don’t know much about what Greenland sharks do, but we do know that whatever they do, they do it painfully slowly – and this results in an astonishingly long lifespan. Peter Bushnell and his colleagues recently published a landmark study in Science that reveals just how long these enigmatic sharks live.

Photo by Nick Caloyianis | National Geographic Creative

For societies of hunters and fishermen in the Arctic Circle, the Greenland shark that was once a critical resource has become a source of great irritation. For centuries, these First Nations hunted the mysterious, deep-dwelling carnivores for oil for their lamps and food to power their all-important sled dogs. But in more recent years, Greenland sharks have become a nuisance – to the extent that in some places a bounty is paid for their hearts. And according to a recent article published in Science, these hearts are among the oldest vital organs on our planet.

Greenland sharks are notorious for getting themselves entangled in the long-lines and gill nets that fishermen depend upon to make a living from catching halibut. In 2009 it was reported that the sharks made up more than half of the waste disposed of by residents of Uummannaq, a small town on the western coast of Greenland. At the time, technology experts were suggesting that Greenland shark remains be turned into biofuel and that shark by-catch could supply the town of 1,300 people with 13% of its energy needs.

This assessment caught the interest of Dr Peter Bushnell, a biologist at Indiana University South Bend, and Dr John Steffensen at the University of Copenhagen, who realised that the Greenland shark could be the subject of a case study for research that Bushnell was carrying out with Dr Richard Brill of the Virginia Institute of Marine Science. Bushnell and Brill’s studies in Virginia examined the potential of electropositive metals to reduce shark by-catch. After six months of experimenting in Greenland, the shark repellent proved to be ineffective, but the shark with the coldest and most northerly distribution in the world had captured Bushnell’s and Steffensen’s curiosity. ‘The more we delved into it, the more interesting and odd it got to be,’ explains Bushnell. ‘These are incredibly large, slow-growing, mysterious animals and we know very little about them.’

The Greenland shark is the largest elasmobranch native to polar waters and can be found all along the Arctic Circle from eastern Canada to north-western Russia. Between 1770 and 1963, thousands of Greenland sharks were harvested for their livers, which provided oil for lamps. Trade reports suggest that every year from 1890 to 1940 more than 30,000 animals were killed in Greenland’s waters alone. This brief period of commercial importance gave rise to studies by Danish and Norwegian researchers, but for the most part the Greenland shark has remained what Bushnell describes as ‘an enigma wrapped in a conundrum’. And the more he tried to unwrap it, the more interesting and bizarre it became.

Greenland Sharks: Old and Cold

A remarkable creature lives beneath the ice floes of the Arctic. Greenland sharks swim excruciatingly slowly, have been known to eat polar bears and live for an implausibly long time. Peter is bringing their mysteries to the surface.