West African Sawfishes: A window into their Lost World

Ruth Leeney speaks to Nigel Downing about his in-depth research on live sawfishes in West Africa in 1974 and 1975. Nigel’s project came to an abrupt end after only 18 months when funding was withdrawn and he subsequently switched to laboratory-based research to complete his PhD. Forty years later he and Ruth worked together to resurrect some of the data he had so painstakingly collected in the Gambia and Senegal. No stranger to the region, Ruth herself had spent much time there searching for the now-elusive ‘river monsters’. Nigel’s data brought to life a West Africa unknown to her, where rivers teemed with juvenile sawfishes. His stories give an inkling of what has been lost: thriving populations of these unique fishes that were probably observed year in, year out by communities along coasts and rivers at that time.

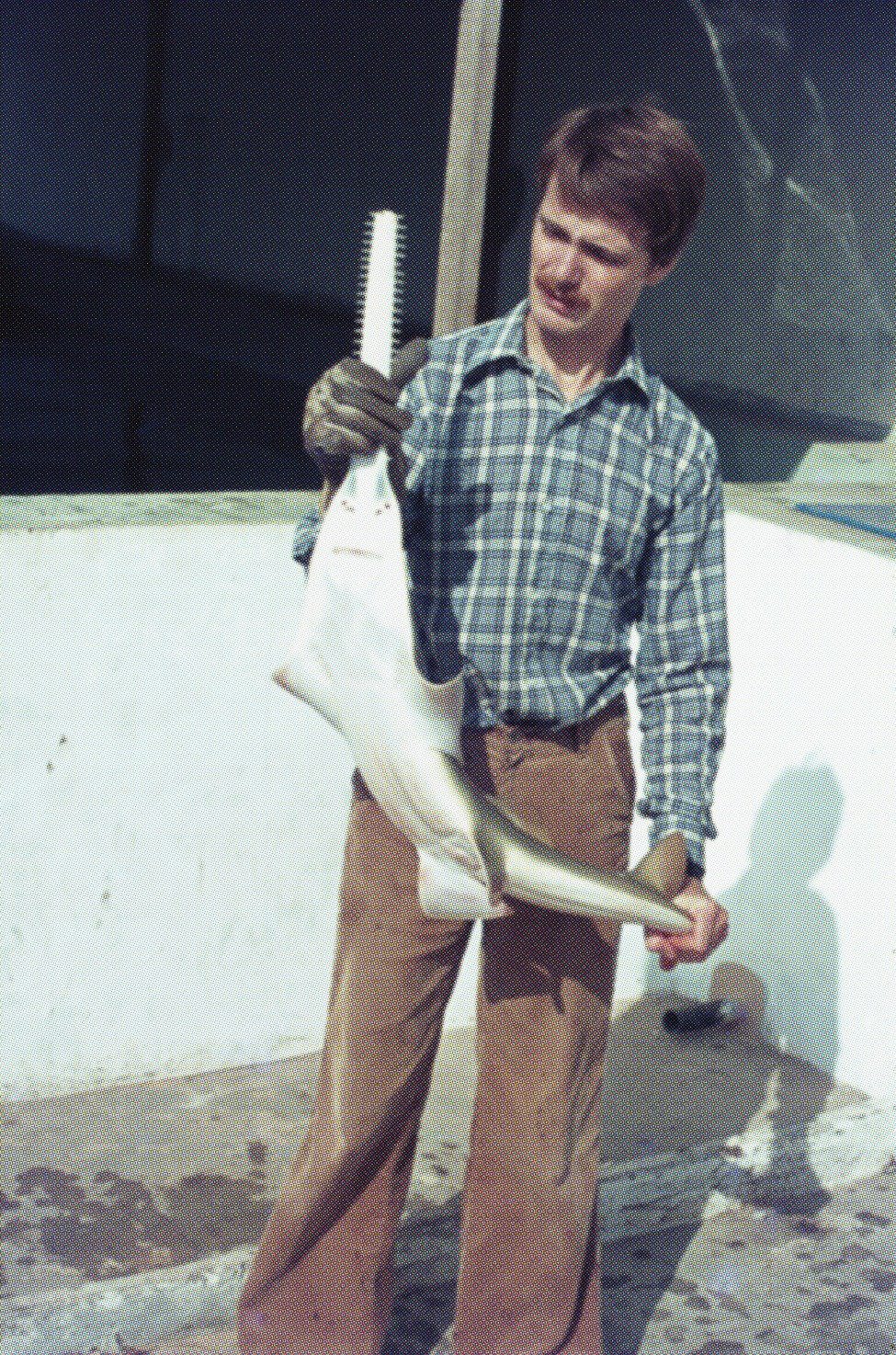

Photo by Nigel Downing

Ruth Leeney speaks to Nigel Downing about his in-depth research on live sawfishes in West Africa in 1974 and 1975.

What were your research objectives in West Africa?

Dr Jean Maetz, a French physiologist who ran a radio-isotope laboratory in the south of France, was keen to discover how elasmobranchs survive in fresh water. He proposed that I find suitable animals, catch them, look after them in captivity locally and then arrange the transport of about 20 of them by air to his laboratory. Then I would work with him using radio isotopes to study the flux of water and ions in and out of the fish under experimental conditions. This last part I never achieved.

Ambitious and exciting goals! Where did the idea for the project come from?

When as an undergraduate I listened to a lecture about osmotic and ionic physiology, I was informed that cartilaginous fish were stenohaline – unable to tolerate large variations in salinity. While there are teleosts (bony fish) that can move from sea water to fresh water and vice versa, salmon being the best-known example, we were told that elasmobranchs were restricted to the sea. However, I knew otherwise. As a young boy in South Africa I was well aware of the Zambezi shark (bull shark), which had been held responsible for a spate of attacks off Durban’s beaches in the 1960s. I even remember an ambulance arriving to pick up a victim from a beach where we used to swim. I also knew that this shark swam up rivers and had frequently been observed in fresh water. Further, having spent several months working at the Oceanographic Research Institute at the Durban Aquarium before going up to university, I knew that sawfishes were also found in rivers as well as the sea.

So, three things compelled me to do this project: I really like sharks; field work was my thing; and I was curious to find out how euryhaline elasmobranchs control their salt and water balance (osmoregulate) as they move between salt water and fresh water.

Were you aware that sawfishes were present in your study areas when you first started the project in The Gambia and Senegal?

My initial plan was to head back to South Africa, use the Durban Aquarium facilities and collect from the rivers and estuaries of Zululand, but that fell through. Dr Maetz said he had heard there were sawfishes in West Africa and so, as a result of hearsay, I ended up working between the Gambia and Senegal, both of which proved to be excellent places to capture bull sharks and sawfishes. By that point I had realised, from my time at the Durban Aquarium, that keeping bull sharks alive and healthy in captivity was going to be far more difficult than looking after sawfishes. The latter can happily spend hours on the bottom using their spiracles to ventilate, whereas bull sharks need to keep swimming. For that reason, sawfishes became my primary study species.

Seeking Madagascar’s sawfishes

Based in one of the world’s most unusual and unexplored ecosystems, Ruth aims to unravel the mystery of Madagascar’s sawfishes. Which species are present? What threats do they face? Can communities be convinced to protect them?