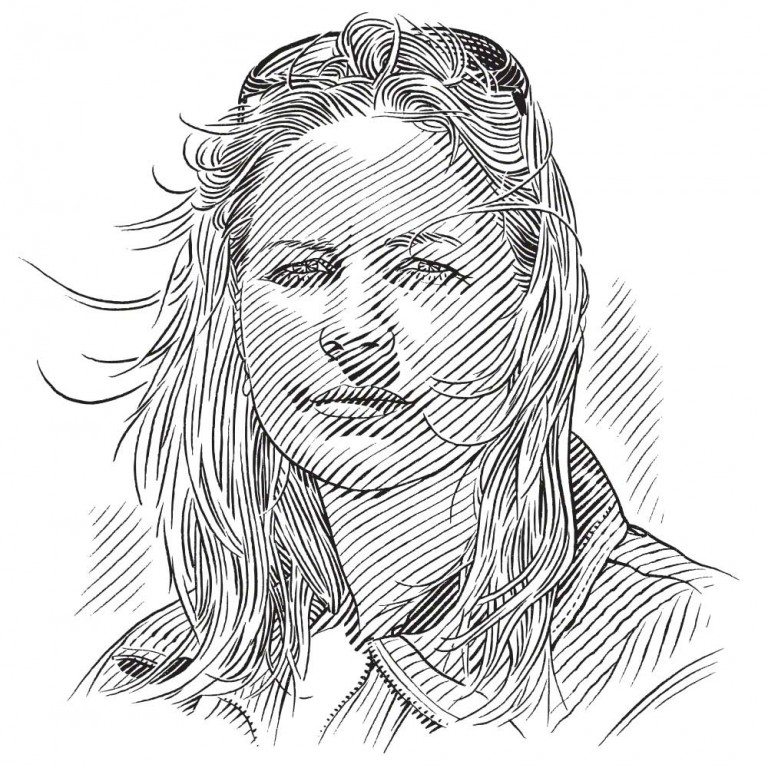

Alison Kock and the Island of Giants

For marine biologist Alison Kock, False Bay’s Seal Island has become a scientific holy land. Philippa Ehrlich finds out more about her connection with this iconic landmark and its famous residents.

Photo by Alison Kock and Enrico Gennari

For most False Bay residents, Seal Island is a rocky silhouette 17 kilometres away from the land that only looms into view on crystal clear, calm days. It is a place shrouded in both fascination and abject terror. Its jagged shores are home to 75,000 Cape fur seals and five species of sea birds. It is also the mythical hunting ground of the most dreaded and talked about member of False Bay’s vast ecosystem: the great white shark.

For marine biologist Alison Kock, the island has become a scientific holy land. Over the past 12 years she has made hundreds of pilgrimages to its hallowed waters and has dedicated most of her waking hours to learning about great whites in False Bay and examining their relationship with local ocean users.

For South Africans her name has become associated with everything shark; Shark Spotters, shark science, shark conservation, shark nets and shark attacks.

Kock’s connection with the most misunderstood fish on the planet was forged completely unexpectedly and kilometres from the sea. Fifteen years ago, whilst studying marine biology at UCT, she spent her weekends managing a car wash in Table View. One very busy Saturday morning she walked over to yet another car, opened up its boot and saw something that stunned her: a pile of photographs of a great white shark fully airborne just off Seal Island. She could not believe what she was seeing, ‘Oh my gosh! Is that real? These big white sharks totally out of the water! Is that doctored?’

She had been studying marine biology for three years but had never heard a whisper about great whites breaching. That image electrified a string of questions that would propel the next 15 years of her life.

She investigated the source of the photograph and was determined to get herself a spot on his boat. A few weeks later, she found herself on the deck of Chris Fallows’ and Rob Lawrence’s shark-watching vessel. For Kock, it would be the first of hundreds of real life encounters with great whites: ‘I went out there and saw these sharks flying out of the water and attacking seals right next to the boat and I couldn’t believe this was right on my doorstep.’

From that very first trip, she became a volunteer on Fallows’ and Lawrence’s boat, and for the next two years she guided tours, washed boats and worked in the office, but a new goal was taking shape. Every day she would go out to sea with a boatload of tourists who were equally amazed by the animals, and with their awe, came curiosity. At the time, there was very little scientific information on South African great whites. Apart from a few statistics based on the number of animals caught by shark nets in KwaZulu-Natal, we did not know how big South Africa’s great white population was and there was not a shred of research about their behaviour. ‘I just realised that we knew nothing about these sharks. There was no literature. The clients continually asked us questions and we just couldn’t give them any answers,’ Kock remembers.

The Shark Spotters

The Shark Spotters programme in Cape Town, South Africa, improves beach safety through both shark warnings and emergency assistance in the event of a shark incident. The programme contributes to research on shark ecology and behaviour, raises public awareness about shark-related issues, and provides employment opportunities and skills development for spotters.