Editorial #08

Winter | December 2017 issue

Photo by Olivier Born | © Save Our Seas Foundation 2017

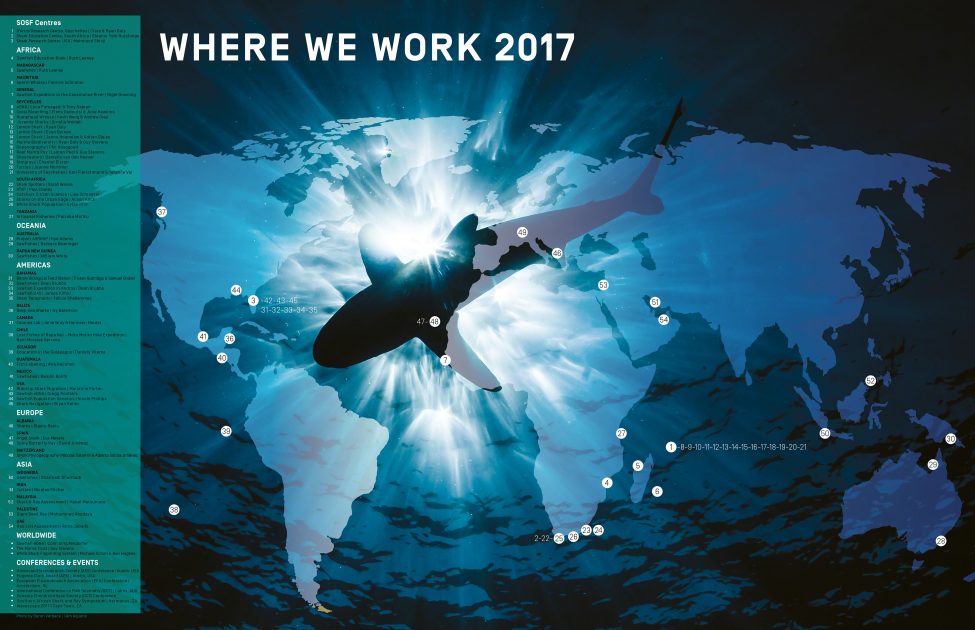

Having been born in the early 1970s, I grew up when the environmental movement was taking off. Although the plight of sharks was first highlighted in the ’80s, the unfortunate timing of Steven Spielberg’s Jaws (1975) hampered the public’s empathy for the declining shark populations in those early years. Even today, the lingering effects of the film remain an obstacle to shark conservation, despite a much better understanding of these mysterious creatures of the oceans. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species registers more than a thousand species of chondrichthyan fishes (sharks, rays and chimaeras), close to half of which are classified as Data Deficient; an estimated quarter of all chondrichthyans are listed as Threatened. And while a significant number of new species have been discovered over the past couple of decades, some of these are likely to disappear before they are even described. These ‘lost sharks’ are at the mercy of greater attention being paid to the more charismatic, and often less threatened, species.

In this eighth issue of the Save Our Seas magazine, we present a new series of exciting stories from around the world. They tell of the work, and life passion, of scientists, conservationists and educators, and some feature lesser-known chondrichthyans. For example, in June I was fortunate to join an expedition led by Dr Dean Grubbs to the West Side National Park on Andros Island in The Bahamas, one of the last healthy refuges for the smalltooth sawfish. In two weeks of intense fishing for these elusive and threatened batoids, we managed to catch only one (but close to 200 other sharks). The work done by Dr Grubbs and his colleagues in The Bahamas and in the Florida Everglades and Keys is revealing crucial new information about this enigmatic species, as well as the relevance of marine protected areas.

Last year, I joined National Geographic Magazine photographer Thomas Peschak on a research expedition led by Dr Pelayo Salinas-de León to Darwin and Wolf islands in the Galápagos. The Darwin and Wolf Marine Sanctuary, proclaimed in 2016, harbours one of the highest abundances of sharks on the planet, and each shark is estimated to be worth about $5.4-million over its lifetime. Known for its remote and evolutionarily unique ecosystem, the Galápagos archipelago is actually not that isolated as far as highly migratory marine species are concerned.

A decade ago, while visiting Argentina’s Península Valdés, I was surprised at the similarities in terms of wildlife between it and Dyer Island in South Africa. The exception was that orcas were the dominant predator in Patagonia, whereas white sharks were number one in the Western Cape. In recent years, however, a couple of orcas have taken a liking to sharks in False Bay and at Dyer Island and have established their supremacy, effectively rearranging the ecosystem’s food web.

As I write these few lines while attending the World Conference of Science Journalists, I want to recognise the significance of communicating science to a broader public audience. All scientists witness incredible observations and experiences and although their principal role lies in reporting their findings in scientific publications, their part in communicating to the public remains nonetheless essential. This magazine presents a variety of articles that will hopefully inspire readers around the world and help them to understand the importance of all the creatures that share our planet.