Exploring Personality in Sharks

Félicie Dhellemmes is studying the behaviour of juvenile lemon sharks to understand what might be called ‘shark psychology’.

Most people think of sharks as being fearless, but in reality some are bolder than others. This is true between species, as illustrated by oceanic whitetips being notorious for their curious and confident behaviour, whereas scalloped hammerheads are timid and sensitive. It is also true among individuals of the same species: divers at Tiger Beach in The Bahamas frequently comment that, of the tiger sharks encountered there, ‘Hook’ is timid whereas ‘Emma’ is more inquisitive. At the Bimini Biological Field Station, also in The Bahamas, the differences in behaviour shown by individual sharks – also called ‘personality’ – have been the subject of a long-term study. And now, more than four years on, we are no longer looking at a hypothesis. Sharks have personality, just like you and I!

How do we measure personality in sharks? Humans we can ask to complete a simple questionnaire and then evaluate the responses, but the challenge is far more complex when large marine predators are involved. Firstly, the model species needs to be carefully selected. It must be abundant, thrive in captive conditions and be easily recaptured for multiple testing. Secondly, the scientific team must decide on tests that are relevant to the species’ behaviour in the wild. For instance, to measure individuals’ sensitivity to stress, different stimuli will have to be applied to the blacktip shark (a highly sensitive species) and the nurse shark. The nurse shark’s propensity for hiding under ledges justifies using emergence from a hide as a test, whereas exploration of an enclosure would work better for the more mobile blacktip shark. And finally, a series of pilot studies that enable us to clarify our protocol should be conducted in order to pick the test that will bring to light the animals’ personality traits most successfully.

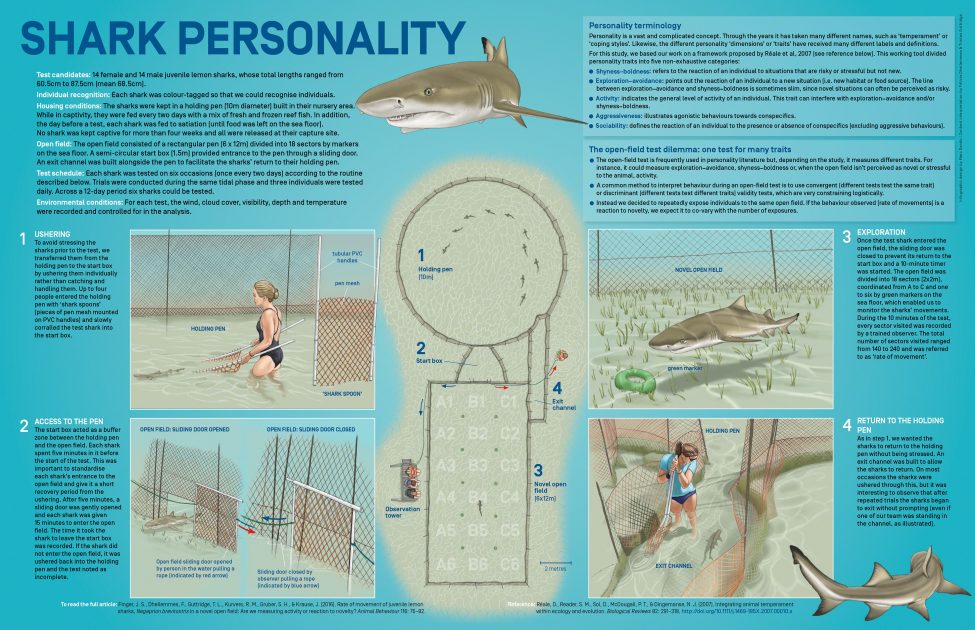

At Bimini, hundreds of juvenile lemon sharks Negaprion brevirostris can be captured and recaptured each year and maintained in semi-captive holding pens built in the shallows. For this species we found that one of the most efficient ways to perceive personality is via a novel open-field test. Put simply, the sharks are placed in a large enclosure they don’t know and their movements are monitored over a 10-minute period. They are then retested a few days later to see whether their behaviour is consistent. In general, the sharks explore the new enclosure uniformly, but some consistently explore it faster than others do, proving the presence of personality.

But what are we measuring? The interpretation of personality tests adapted to animals is a recognised stumbling block for animal behaviour specialists. In our case, the rate of movement of individual sharks might vary because each one reacts differently to the stimulus provided by the new enclosure. Alternatively, the explanation could be that, in the absence of a stimulus, their baseline activity is different anyway. It is therefore important to understand how the novel open field is perceived by juvenile lemon sharks. Does this test produce enough novelty to elicit a behavioural response – and can it therefore be used as a reliable method to measure shark personality?

Shark Persona

Did you know that individual sharks have different personalities? Felicie is working with lemon sharks to discover what impact their different characters might have on their lives. Could the persona of a shark cause it to live longer or be braver than other sharks?