Feeling the heat

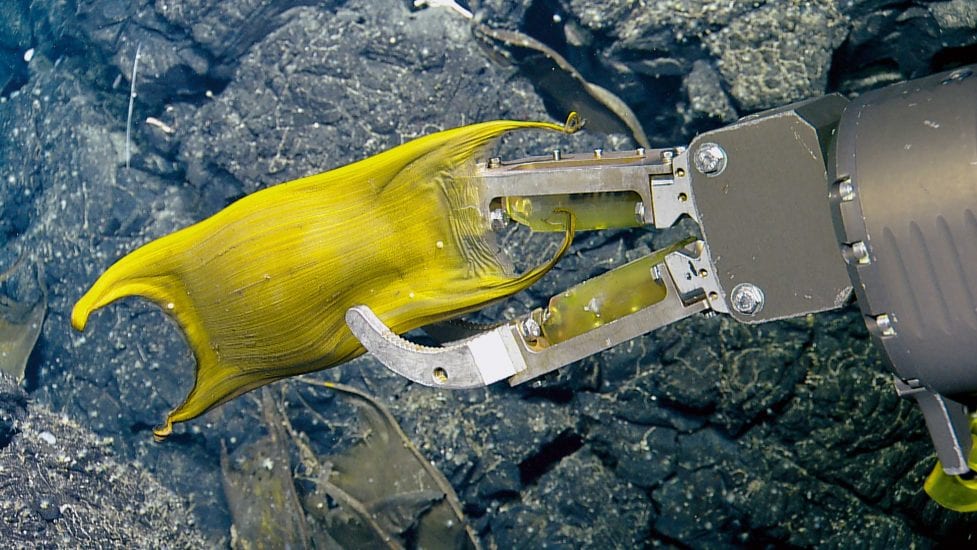

A new publication brings to light a startling find and reminds us of how deep-dwelling sharks, rays and skates are brilliantly adapted to their environment. The deep sea remains one of our least explored and understood habitats on earth. As fishing and mining encroach into deeper waters, even the furthest reaches of our oceans are no longer safe from exploitation. The discovery by Pelayo Salinas de León and his team that the deepest-dwelling skate on earth makes ingenious use of hydrothermal vents in the Galápagos is, perhaps, a reminder that we stand to lose species and habitats before we’ve had a chance to document them in a realm that holds some of the clues to the origins of life on earth.

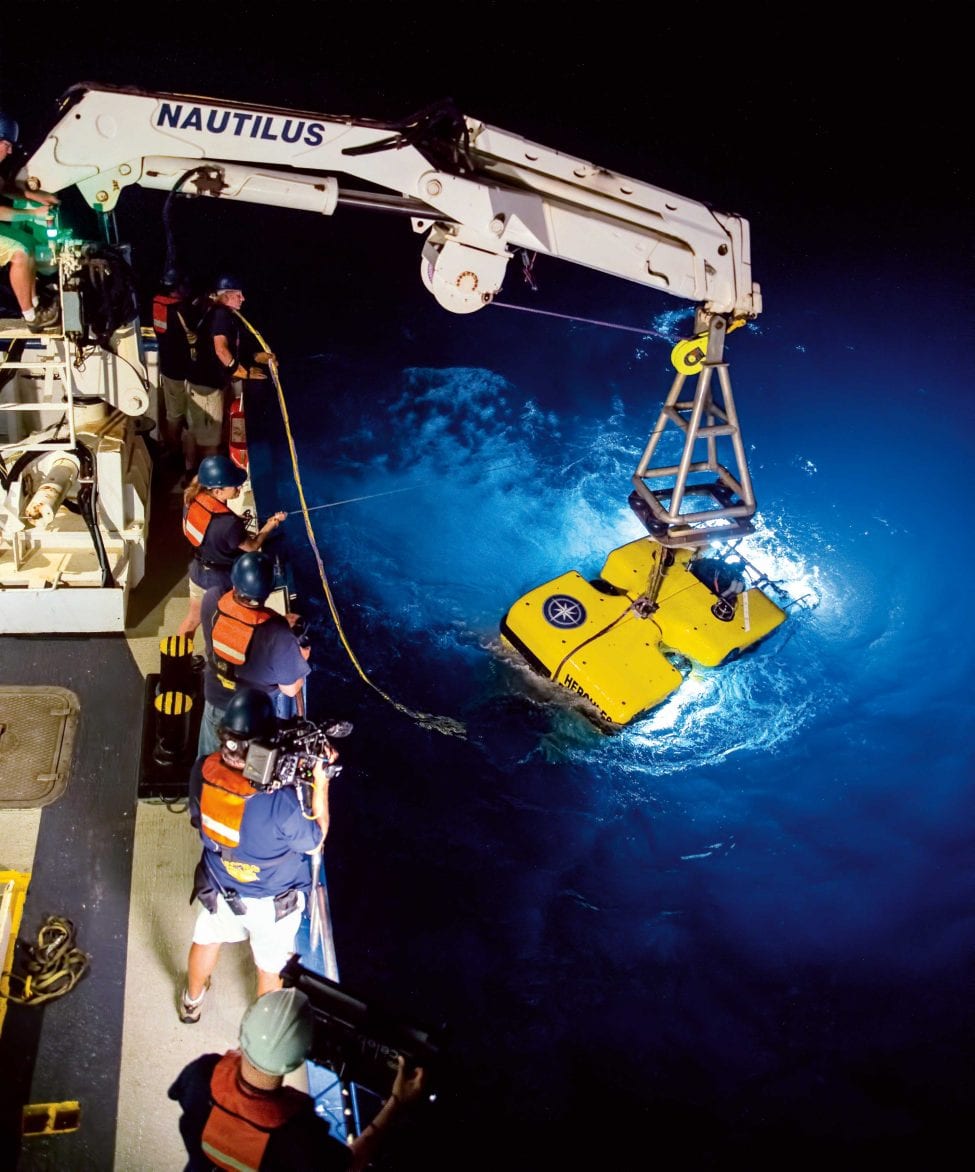

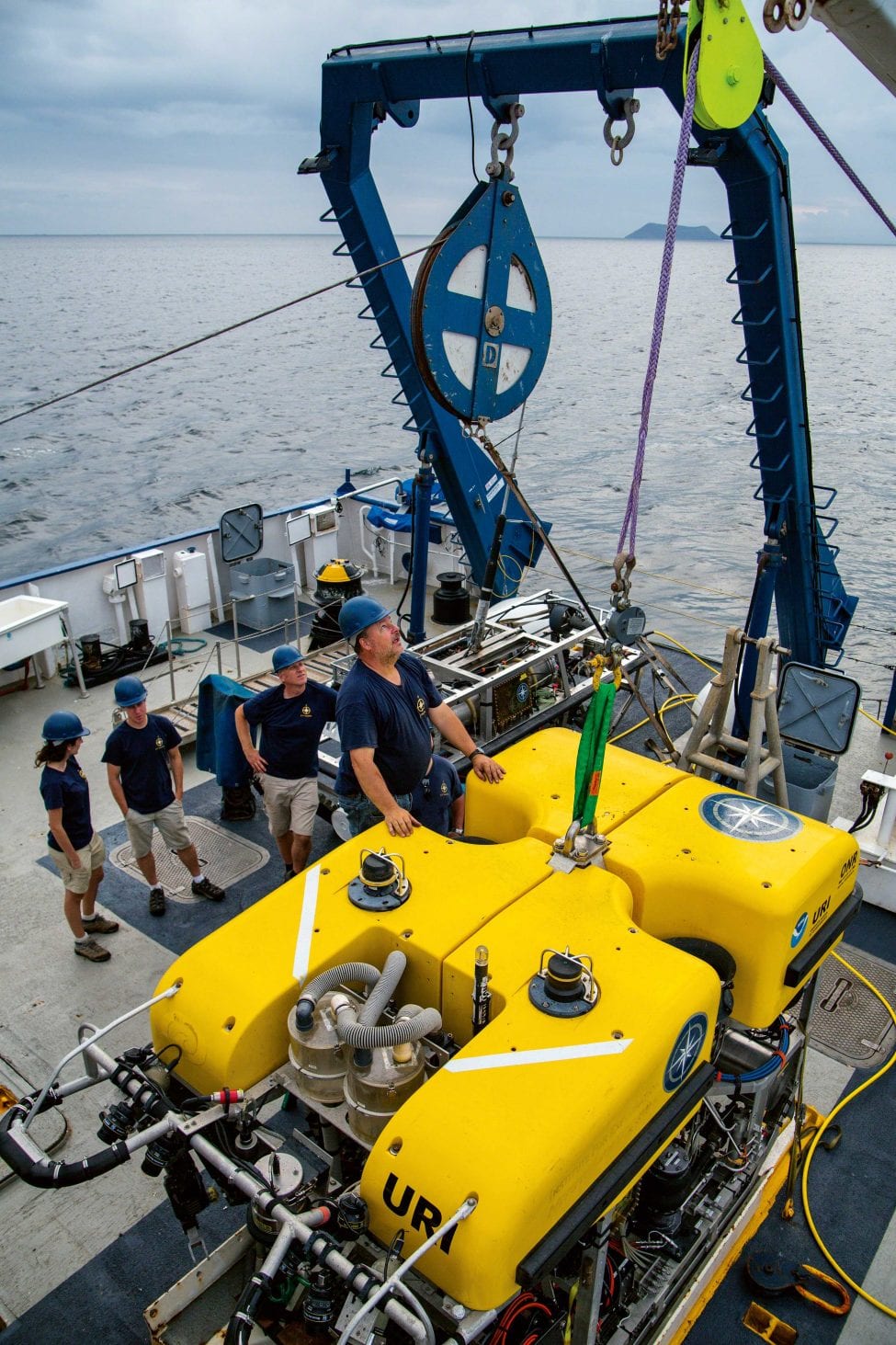

Sink 8,000 feet (2,400 metres) below the surface of the Pacific Ocean and light filtering from the surface dwindles to nothing, leaving an inky blackness. In the absence of life-giving sunlight, it seems improbable that our deepest oceans are anything but lunar landscapes. So when, in 1977, a remote-controlled camera sled gliding along the sea floor recorded a spike in ocean temperature, scientists dismissed it as a glitch. Only once they had retrieved the camera and started sifting through the stills it had captured did they realise that this ‘irregularity’ in the temperature readings matched a series of photos that revealed beds teeming with clams and mussels – a sea floor more alive than seemed possible for that depth.

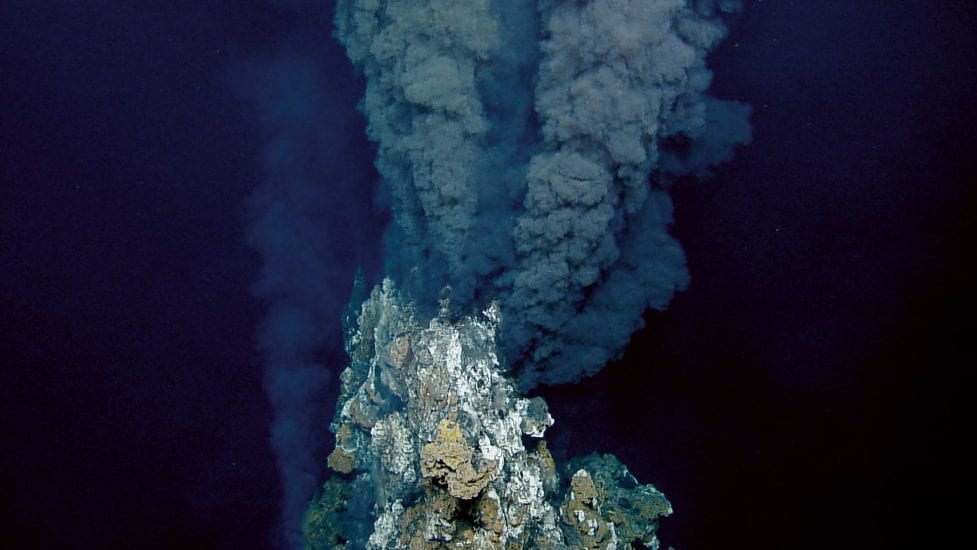

On the equator and along the submarine lava plateau that is the Galápagos Platform in the eastern Pacific, 13 volcanic islands and a number of sea mounts emerge from the ocean. Lying 1,200 kilometres (745 miles) west of Ecuador, these islands, the Galápagos, have captivated scientists since Darwin pondered over their finches and formulated his first inklings of the theory of evolution. It was here that Rob Ballard and Richard von Herzen led the Galápagos Hydrothermal Expedition and discovered the reason for a surprising oasis of life at depth: hydrothermal vents belching water heated by magma where the earth writhes with growing pains. Their discovery changed the way science debates the origins of life on earth. The Galápagos, it seems, continues to challenge and shape the way we understand biodiversity, its evolution and its relevance to our lives.

Hydrothermal vents are found near sites of volcanic activity. They are typical of mid-ocean ridges, where the earth’s tectonic plates are moving apart and away from each other as new ocean crust is formed. Sea water permeates the ocean crust, percolating into the rock through fissures, and is heated by magma boiling deeper down. Where it bursts to the sea floor’s surface again through vents, the water might be at any temperature between 60 and 460 °C – much hotter than the ambient 2 °C typical of water at this depth. The process of heating causes a series of chemical reactions, as does the subsequent process of coming into contact with cool, surrounding sea water once again when the heated water bursts out of the vents.