Finding Timothé

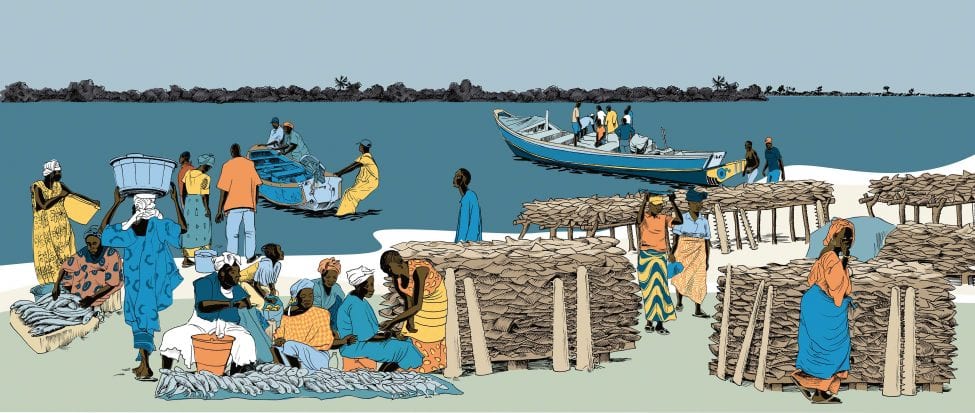

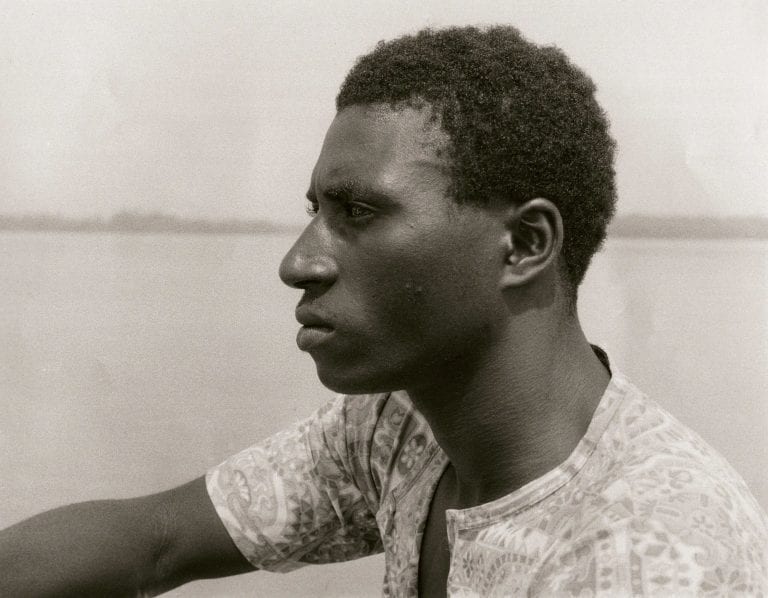

Forty years ago, Nigel Downing found himself drifting along the waterways of Senegal in search of sawfishes. His mission? To collect live specimens in order to answer a specific question: how do they move from salt water to fresh water and survive? Spurred on by speculation, Nigel had scoured fish markets and interviewed fishermen, but was no closer to catching enough animals for his study. His salvation came in the form of an enigmatic Senegalese fisherman named Timothé; together they would uncover an extraordinary population of sawfishes. When the time comes to return to Senegal four decades later, the question Nigel wants to answer is not only what has happened to West Africa’s disappearing sawfishes, but also what has become of his friend who’d first made this research possible.

Photo by Nigel Downing

As we walk silently along the sandy path through the shaded Casamance village, I tap the shoulder of Pierre Bassène who leads the way. ‘Pierre, don’t tell him,’ I whisper. ‘Let’s see what he says!’ Already overwhelmed by what he’s about to witness, Pierre nods and points ahead.

This story began in the 1970s. As a 23-year-old PhD student I was searching for sawfishes in Senegal’s Casamance River. I needed live specimens for my research, to understand how they balance their body’s fluid and dissolved salt levels. I had still been an undergraduate at Cambridge University when I had eagerly challenged the claim by the head of the zoology department that sharks, rays and skates were strictly marine and never found in fresh water.

According to the theory at the time, their bodies only functioned in a narrow salinity range; they couldn’t move from the salty ocean into the sweetness of fresh water. I, however, had a different idea – and so the topic of my research was born. I would investigate how some sharks, like the bull shark Carcharhinus leucas, and sawfishes Pristis spp. are able to move from salt water to brackish water and to fresh water. What do their bodies do to help them cope with these changes? How are they adapted so that the concentration of salts and ions in their blood stays balanced, despite changes in their environment?

In the simplest terms, when a fish such as a salmon is in sea water its body cells are more dilute than the surrounding sea. When it moves to fresh water the opposite happens; its body cells are more concentrated. Water then floods in and at the same time the fish loses precious body salts. We understood how salmon adapt while moving from one environment to the other. However, sharks and rays use a different mechanism, and no one knew how they could tolerate fresh water. I wanted to find out – but first I had to find my shark or ray.

Sawfish hunt: return to Senegal

In the 1970s, Nigel discovered a treasure trove of sharks and rays that were using the Casamance estuary in Senegal as a nursery ground. He also found an abundance of sawfishes. More than 40 years on and every indication is that the sawfishes in the region are all but extinct. Nigel is going back to find out if those indicators are right.