Lemon Sharks are how old?

The story – and implications – of new research led by Jill Brooks that extends the age of lemon sharks using genetic information from 25 years of research.

Photo by David Doubilet | National Geographic Creative

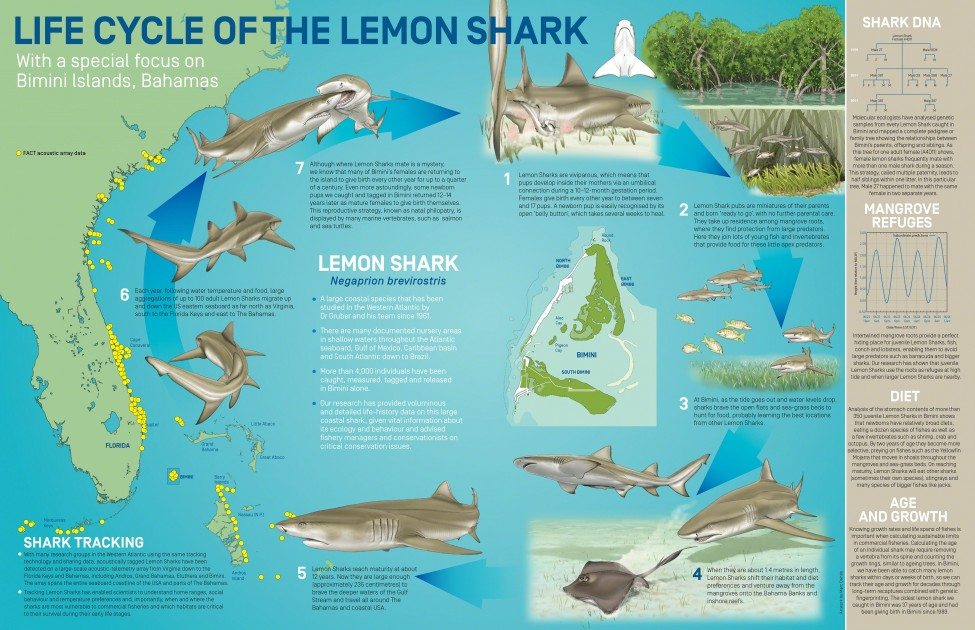

As the saying goes, age is just a number. But when managing sharks, it can be a very important number. In Bimini, The Bahamas, we have found lemon sharks that are as old as 37 years – almost twice as old as previously thought. For some perspective, that’s like finding out people – which we’ve known previously to live to a maximum of 122 years – can live to be 205!

But how do you ‘age’ a shark? One way is to look at its vertebrae. A shark ‘lays down’ new layers of cartilage as it grows, just like the rings of a tree, and these give a basic idea of how old it is. Unfortunately, the shark has to be dead before you can age it in this way and these growth rings are difficult to see. Furthermore, different species of sharks grow and lay down rings at different rates and the rings can be blurry and impossible to interpret.

There is, however, another way to age a shark. You capture it, tag it, inject it with a dye, release it – and then hope to catch it again one day in the future. The dye marks the shark’s vertebrae at the time of capture, so if it is caught again scientists can count the number of rings that have formed in a known amount of time. They can then compare against growth curves how much the shark has grown in that time period. Normally sharks grow a little bit less each year as they get older, until they barely grow at all towards the end of their lives.

And why is it important that we know for how long lemon sharks live? Well, it helps to answer a pretty impossible question: how many lemon sharks are there in the ocean? With some complicated mathematical models and biological data (like the maximum lifespan of lemon sharks), fisheries scientists can make pretty good guesses. If we know how many pups a female shark has each year and for how many years they can live, we can estimate the rate at which sharks die from natural causes and the time required for local populations to rebound from declines. However, if any of this information is wrong when scientists define how many sharks fishermen can catch, collapses in shark populations could be the result – as has happened in the past.

Having accurate life-history data is important for the sustainable management of any fish species, but for sharks, with their slow reproductive rate and late age of maturity, it is even more important. In the only growth study ever conducted on lemon sharks, Dr Craig Brown and Dr Samuel Gruber captured and injected dye into 2,300 lemon sharks; out of the 55 recaptured individuals, the oldest was 22 years. Until recently, this had been the oldest lemon shark ever recorded and its lifespan has been used as the maximum for the species in fisheries models.

Bimini Biological Field Station (BBFS)

Samuel, better known as Doc, has been studying sharks for 50 years. He discovered how sharks see and even gave us insights into how they think. He founded the Bimini Biological Field Station in 1990, and has been training and inspiring young shark researchers ever since.