Secretive Sevengills

Unravelling the mysteries of enigmatic predators

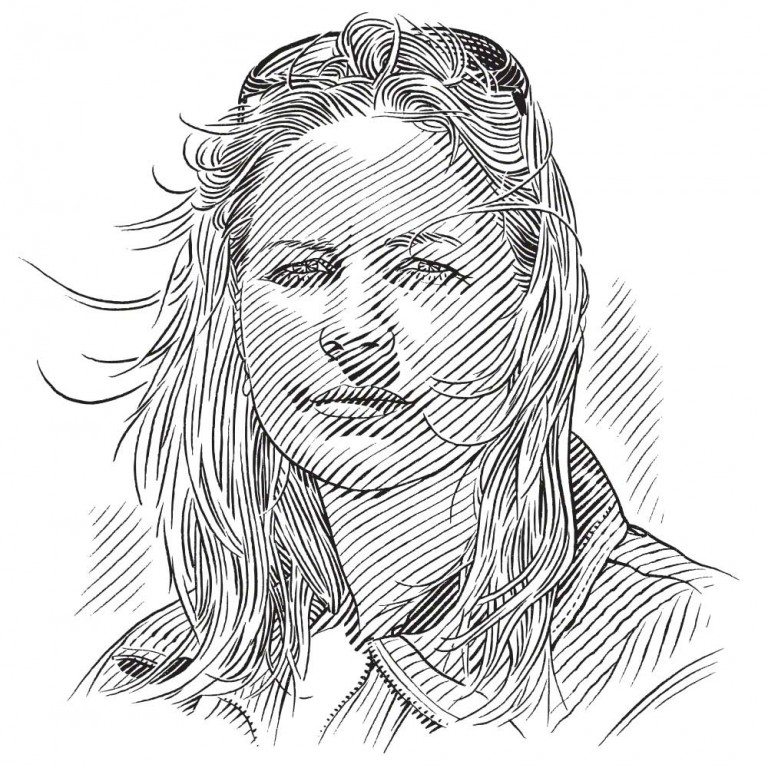

The water is murky and I can’t see more than five metres (16 feet) in front of me. I sigh into my regulator and navigate my way awkwardly through the thick kelp, my bulky scuba kit making my movements cumbersome. After what seems like an endless dive battling through this dense underwater forest, there is still no sign of any broadnose sevengill sharks (more fancily termed Notorynchus cepedianus). As I start to lose faith in this so-called shark aggregation site, my dive buddy and I break through the kelp into a sandy channel. There, cruising placidly in languid circles, are three of the strangest looking sharks I have ever seen: seven gills instead of the usual five, one dorsal fin instead of two, and a broad, almost smiling face. I do a small underwater victory dance and sink to my knees on the sand as the sharks meander over to investigate this clumsy two-legged creature that is watching them so avidly.

To be able to get so up close and personal with one’s study species and observe it unobtrusively in its natural environment is a rare privilege. Broadnose sevengill sharks (or simply sevengills) are apex predators found in temperate seas worldwide. Because they occupy shallow coastal waters, they are vulnerable to human-induced threats that range from overfishing to pollution and habitat loss. Despite this, there are limited management and conservation strategies for these sharks throughout their range, primarily due to large gaps in our understanding of their behaviour, ecology and life history. Miller’s Point in False Bay, South Africa, is a popular dive site that hosts one of the largest known aggregations of sevengills in the world: as many as 70 sharks can be seen on a single one-hour dive. But why these sharks aggregate here, how they move around the rest of False Bay – and more broadly along the South African coast – and what influences the timing, scale and direction of their movements are all questions that remain to be answered. In fact, research conducted globally on the sevengill’s behaviour and ecology is so limited that the species is classified as Data Deficient on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species TM.

The Shark Spotters

The Shark Spotters programme in Cape Town, South Africa, improves beach safety through both shark warnings and emergency assistance in the event of a shark incident. The programme contributes to research on shark ecology and behaviour, raises public awareness about shark-related issues, and provides employment opportunities and skills development for spotters.