Shark Lab at Bimini

Jeremy Stafford-Deitsch outlines the history of the Bimini Biological Field Station, the brainchild of Dr Samuel Gruber that has been operating in the Bahamas for 25 years.

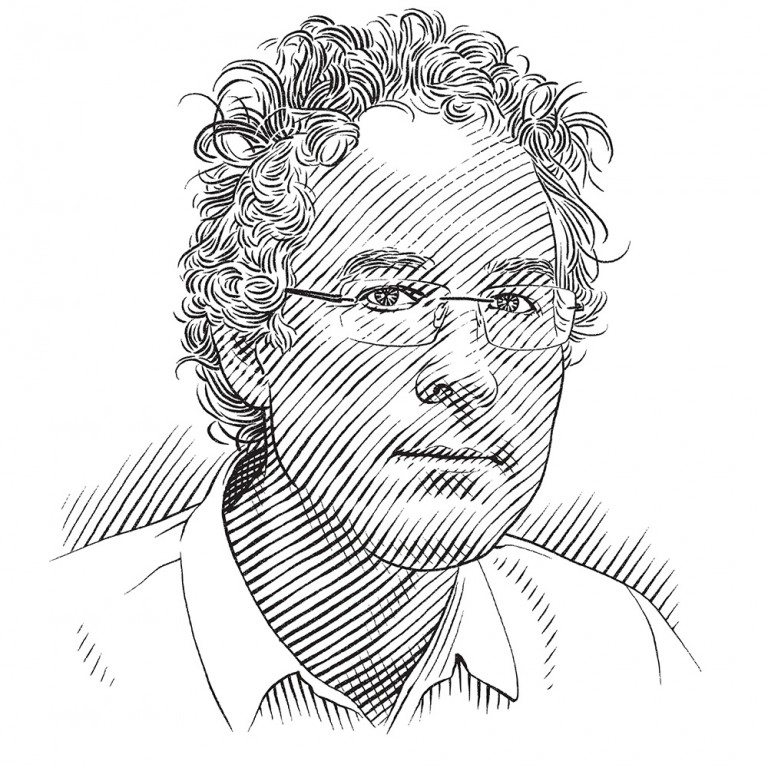

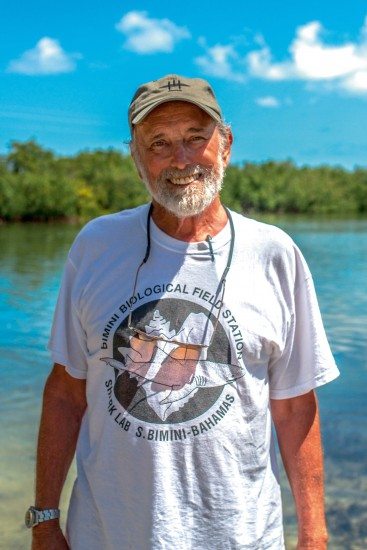

Photo by Samuel Gruber

Dr Samuel ‘Doc’ Gruber had two massive battles with cancer. In late 1989 he finally put the disease behind him and, through sheer hard work, regained his strength. He was in his early 50s and pondered the state of his career: the endless days spent in the University of Miami’s marine school laboratory; the bureaucratic battles required to equip it so he could learn more and more about the vision of sharks but less and less about the sharks themselves; the never-ending hassles to get funding for his ambitious ship-borne research expeditions; the back-stabbing and petty jealousies of university life. It was time for a change in direction.

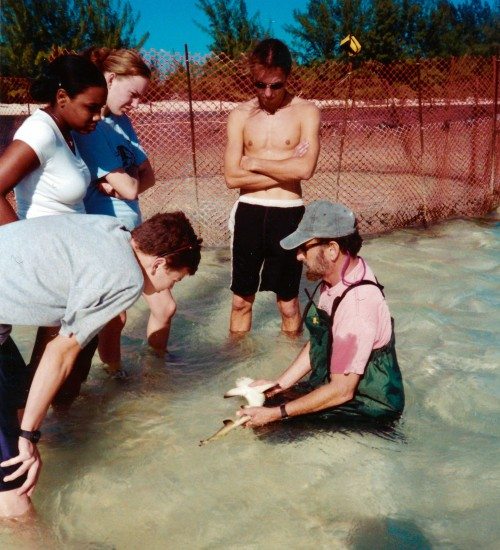

Doc had already spent 10 years visiting the Bahamas on research vessels to study the lemon sharks there. The species was disappearing from the waters of the Florida Keys, another of his study areas, and by 1982–83 it had been fished out. It was at Bimini that he struck gold. The great mangrove-fringed lagoon of North Bimini had a healthy supply of lemon sharks – juveniles of all sizes – and, conveniently, the islands are a mere 85 kilometres (53 miles) from the coast of the United States. More-over, there was something very special about the North Sound that Doc grasped immediately and knew would be enormously significant in the future course of his research: the juvenile sharks had nowhere else to go. If they left the safety of the inshore waters they would in all likelihood be eaten by larger versions of themselves. This meant that they could be studied year after year as they developed, until they were finally big enough to leave the safety of the tangled red mangrove roots, the shallow sea-grass beds and the ever-winding channels.

But, at least in the early days, there was a downside to working in Bimini’s remote and beautiful backwaters. In the 1980s and ’90s they were used by smugglers who were awaiting delivery of drugs and would then rush them in high-speed boats across the Gulf Stream to the United States. The territories of the drug smugglers and the shark researchers (whom the smugglers suspected were drug enforcement officers in disguise) overlapped, resulting in occasionally alarming confrontations. The plethora of crashed aircraft around Bimini back then attested to how cheap the smugglers held human life when set against the fortunes to be made.

Doc was undeterred. He went to see his dean, an interim dean at the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science (RSMAS), and put his proposal to him. ‘I’ve beaten cancer. I have another shot at life,’ he explained. ‘What I want to do is open a marine lab on Bimini, a place of pioneering research. I’ll teach there. I’ll take care of everything. All I need you to do is give the OK.’

‘How do I know you aren’t going to open up a house of ill repute?’ was the reply. A stunned Doc answered that as he was now a tenured professor at the marine school, he could fulfil his university duties there during the week and set up his lab in Bimini over the weekend – and no-one could stop him. But he put the effort on hold.

Soon afterwards, when a new dean, Professor Bruce Rosendahl, was appointed, Doc took the proposal to him and his reaction was entirely positive, but for the proviso that the marine school could not provide him with funds.

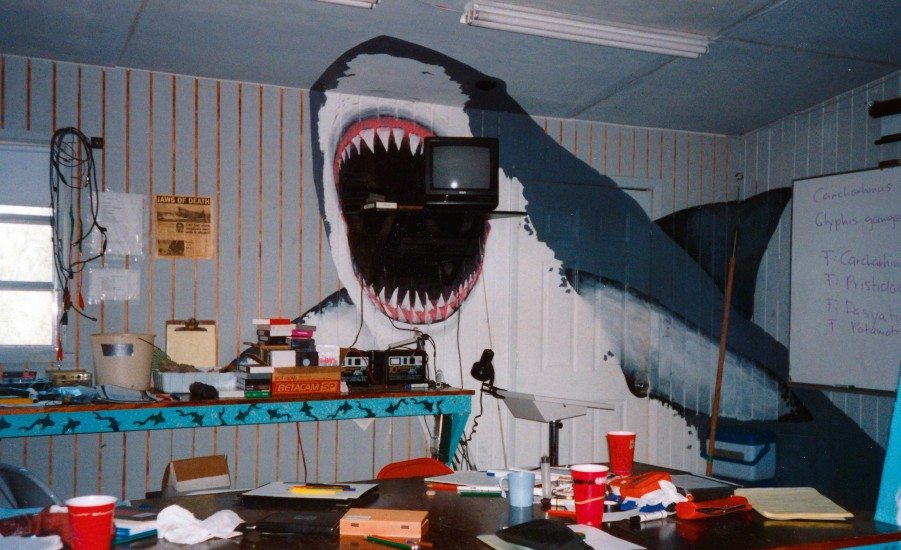

Bimini Biological Field Station (BBFS)

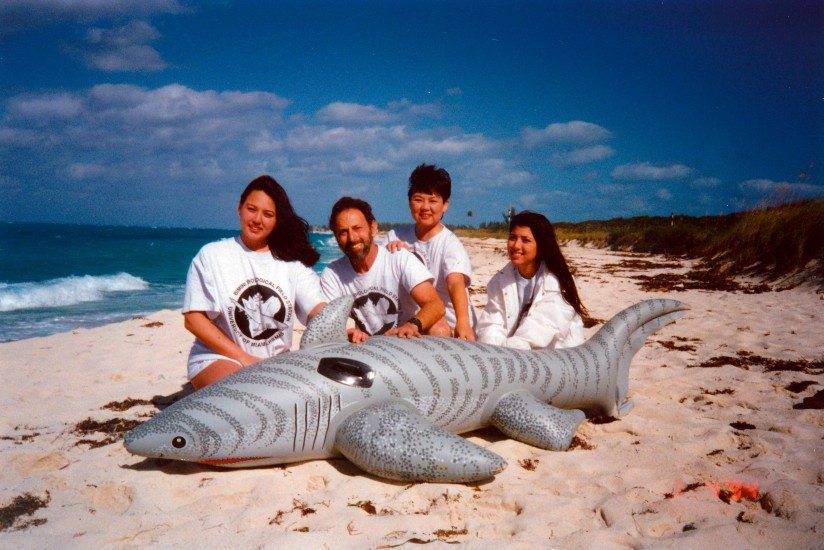

Samuel, better known as Doc, has been studying sharks for 50 years. He discovered how sharks see and even gave us insights into how they think. He founded the Bimini Biological Field Station in 1990, and has been training and inspiring young shark researchers ever since.