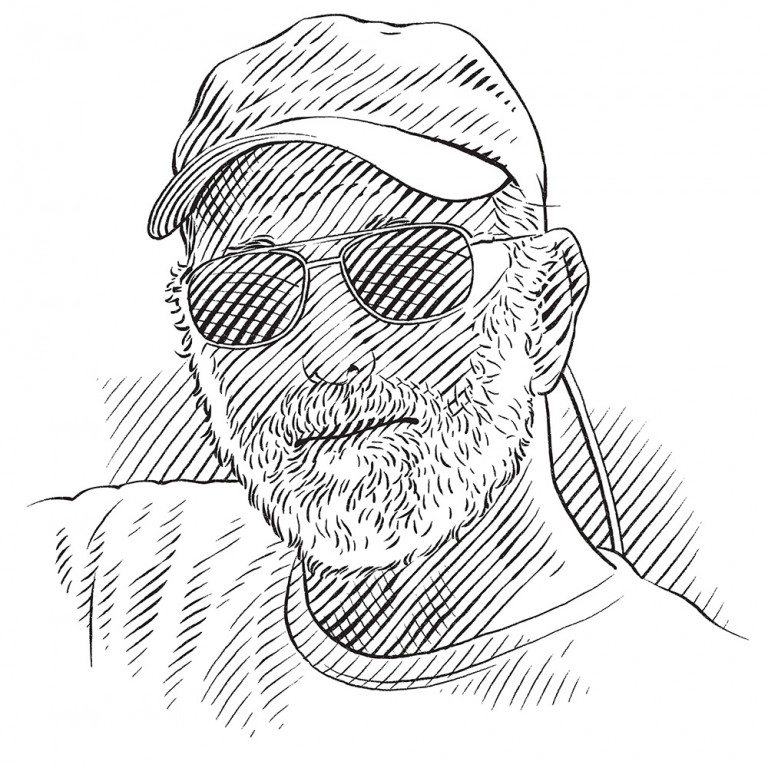

A ‘Pirate’ of the Caribbean

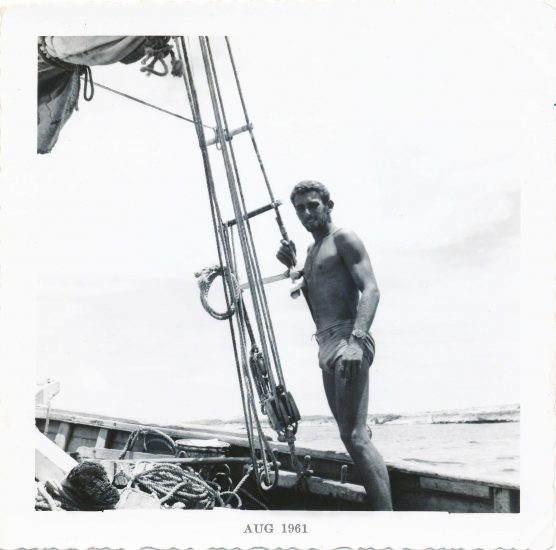

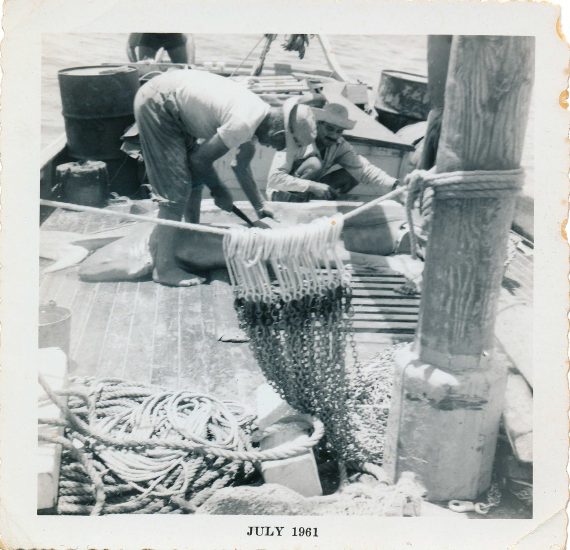

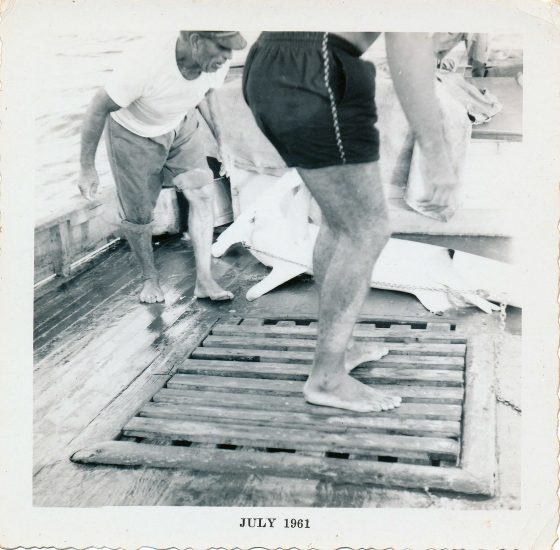

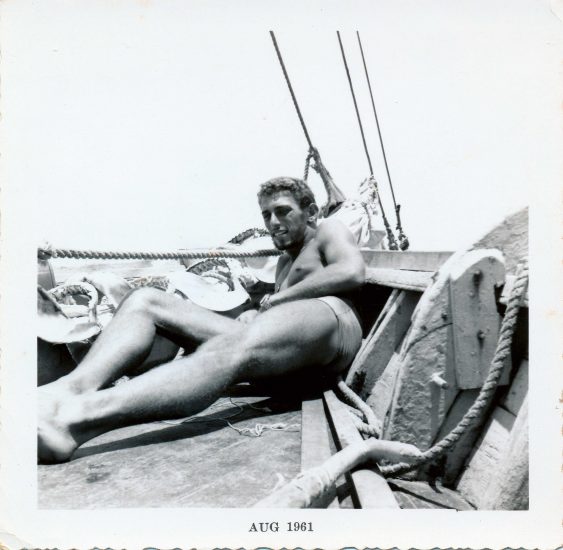

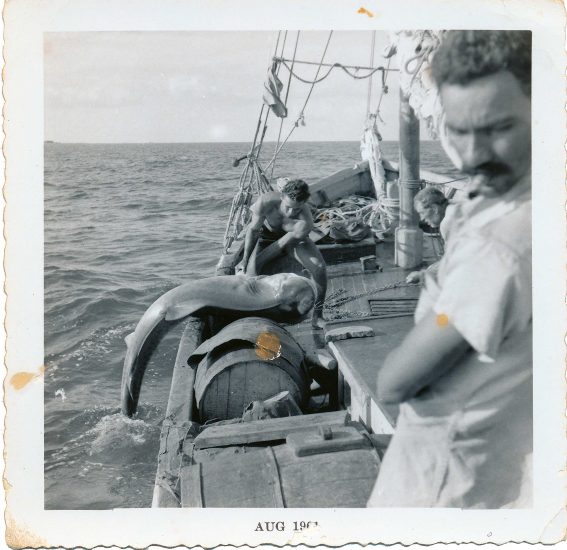

Shark scientist or pirate? Six decades ago renowned shark researcher ‘Doc’ Gruber was a bit of both when he sailed around The Bahamas with Cuban fishermen in the Petra Maria. They were collecting shark skins: the scientific samples. It was an experience etched deep in his memory.

The year was 1961. I had finally made a decision to follow my life’s career. Torn between Air Force jet jockey, professional ballet dancer and marine biologist, I had been persuaded by my father that the most viable and least dangerous path to follow would be the academic route to marine biology. He was a good observer and judge of character so I took him at his word, but failed to mention that my desire was to study sharks.

Even before beginning my 58-year career at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, I decided to carry out my own little research project. I found out that many a Cuban fisherman had grabbed his boat back from Fidel Castro, who nationalised them when he took over the country in 1960. One particular vessel, the Petra Maria out of Caibarien, Cuba, sailed to Miami with the goal of shark fishing for hides that would be tanned into leather. The crew worked for a small company, Florida Caribbean Fisheries, which liked to employ refugee Cubans because they were excellent fishers, despite using primitive methods.

In those days, the Ocean Leather Company was buying up shark skins and tanning them into a leather that was said to be indestructible; workmen’s boots tipped with shark skin would apparently ‘last forever’. The company also manufactured belts, wallets and briefcases as high-end products and was doing very well. In the 1960s, though, it could not get enough of the raw product. Enter Florida Caribbean Fisheries, which agreed to sponsor the Petra Maria’s owner-captain with shark-catching gear.

The vessel’s crew comprised a captain and four deck hands. They were all Cuban and spoke no English whatsoever, having arrived in Florida only a few weeks before. Fortunately, I spoke some Spanish because my roommates in prep school were mostly from Havana. As best I can recall, the captain’s name was Indio, while the most experienced fisher was Antonio, who claimed he started fishing at 12 and was about 70 at the time I met him. He actually hailed from Portugal, but spoke Spanish and had lived in Cuba for years. I have forgotten the names of the other three crew members, but they were rather young and surly.

I still remember the day I parked my little red Fiat Spyder in front of the Florida Caribbean Fisheries office and walked in. With apparent confidence, I asked the owner if I could join the next shark fishing trip. He must have been amused because he agreed instantly while the crew grumbled in the background. You can’t imagine the incongruity between this crew, their vessel and me, the 23-year-old son of a wealthy banker. Nevertheless, I was ready to jump in with both feet and finally learn something about sharks, after having struggled for four years to study them on my own.

The plan was to fish for about a month at the north-western edge of the Great Bahama Bank, poaching sharks. We would be fishing from South Riding Rock to Great Isaac’s Cay, a distance of about 90 kilometres (55 miles). Although I joked that the Petra Maria was my first research vessel, she was in fact an old, salty, 12-metre (40-foot) gaff-rigged sloop with no electrical system, no head, no galley, no lights and no radio. Our only drinking water was contained in a pair of 200-litre (52-gallon) wooden casks on the deck. We were essentially living on an 18th-century fishing boat. Her one modern amenity was a three-cylinder Buda diesel engine that was started by jamming the morning’s cigarette butts into each of the three glow plugs and cranking a hand pump to get diesel fuel into the cylinders. The captain would turn over the engine by hand crank and off she would go, reliable every time.

Once it had been agreed that I could sail with the Petra Maria, the next question came up: what in the world was I going to choose as a research project? I had come across a laboratory at Rutgers University called the Institute of Comparative Serology. The researchers claimed to be able to trace the evolution of a related group of species in a way similar to what we see in genetics research today, but of course this was long before such techniques were even dreamed of.

The research method then was to collect blood serum from different but related species and inject it into a test rabbit whose immune system would naturally raise antibodies to the serum antigens in the sample. I approached the Rutgers team and they enthusiastically accepted my proposal. We decided to use the blacktip shark as the baseline species. They would inject rabbits with the blacktip serum I would collect in The Bahamas. The rabbits would then react to the blacktip’s serum antigens and produce antibodies specific to this shark. The trick was to test the blacktip antibodies on the antigens in the serum of related sharks.

So the plan was for me to collect serum from many shark species and send them to the Rutgers laboratory, where the blood would be processed and tested against that of the blacktip. For example, the more closely related a shark is to the blacktip, the less immune-related precipitation occurs between antibody and antigen. Thus it was possible to specify how closely a particular shark species is related to the blacktip. As the Rutgers scientists had already pioneered such research on other species, I realised it was a unique opportunity to look at shark evolution in the same way. I thought that this was an amazing technique and after communicating with the Rutgers scientists, I learned that I could collect shark blood and store it without refrigeration using a chemical preservative.

Bimini Biological Field Station (BBFS)

Samuel, better known as Doc, has been studying sharks for 50 years. He discovered how sharks see and even gave us insights into how they think. He founded the Bimini Biological Field Station in 1990, and has been training and inspiring young shark researchers ever since.