Back from the brink

Sea Turtles in the Seychelles

Called to the Seychelles more than three decades ago to help ‘fix’ the problem of declining sea turtle populations, Dr Jeanne A. Mortimer is still there – and well satisfied with the nation’s proud conservation record.

Photo by Jeanne Mortimer

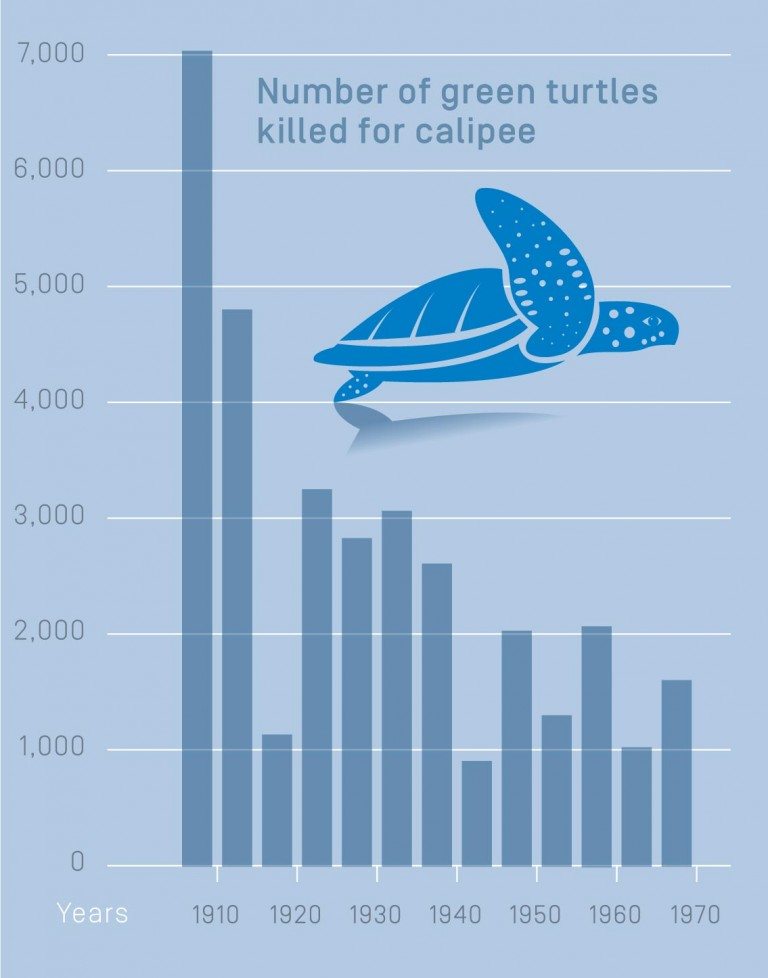

I had never been to the Seychelles. All I knew about the country was what I’d been told by the very few of my acquaintances who had been there and what I could glean from sparsely available books and scientific publications. I knew the primary language was a local French-based Creole and that English and French were also spoken. I was also aware that large numbers of sea turtles, both green Chelonia mydas and hawksbill Eretmochelys imbricata, were killed each year and that people were concerned that the resource was in decline. And by all accounts the country – comprising more than 125 islands strewn across an expanse of more than a million square kilometres of ocean – was very beautiful. My study area was to include as many of these islands as possible, and I was expected to offer advice on how to fix the ‘turtle problem’.

I arrived on the main island, Mahé, in late January 1981, having flown from Miami via London. My job was to assess the status of the Seychelles’ national sea turtle populations and make re–commendations for the management of the turtle resources. Just days before leaving Florida I had obtained my doctoral degree as a student of Dr Archie Carr, a man now considered the ‘father of sea turtle biology’. As an MSc and PhD student, I’d worked with nesting turtles on Ascension Island (in the mid-South Atlantic Ocean) and in Central America, and with turtle-hunting communities along the Miskito Coast of Nicaragua. So I had a lot of experience working to conserve turtles at remote sites and in developing nations.

Once in the Seychelles, I saw the need to approach the problem from several angles. I had to learn about the turtles. How many were there? What was their nesting cycle? Where were their most important habitats? Equally importantly, I had to understand how the local people related to the turtles. What value did they put on turtles, both living and dead? How many turtles were being killed? How and where were they hunted? To answer these questions I needed to go to the places where turtles were facing the greatest threats – and these places included the Outer Islands, where few people lived and much of the important turtle nesting and foraging habitat lay.

Sea turtles on D’Arros

The beaches of D’Arros Island and St Joseph Atoll are very important places for mother sea turtles to come and lay their eggs. Jeanne is training Seychellois monitors to observe nesting turtles and collect data about them.