Great Bear Wild

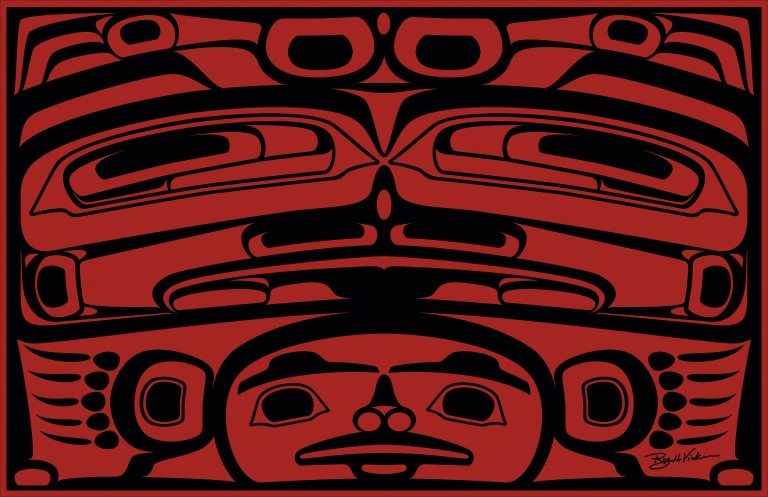

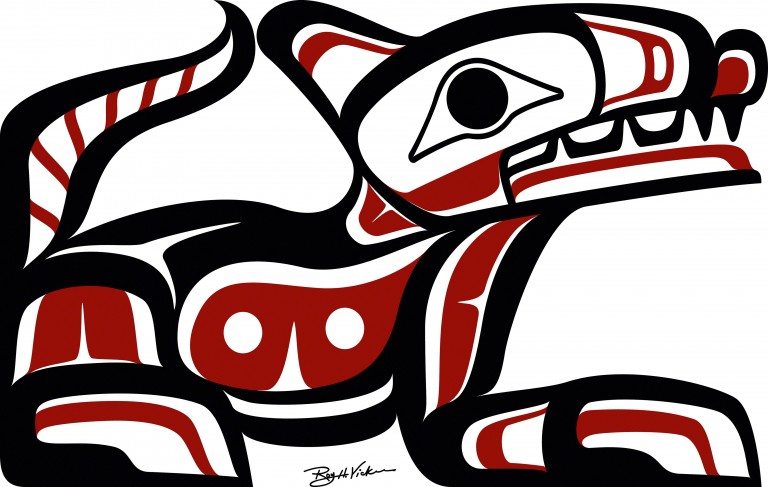

Where forest meets sea on Canada’s Pacific coastline, First Nations have sustainably used an incredible natural bounty for thousands of years. Ian McAllister of Pacific Wild wants to continue their traditions of protection.

The white sandy beaches and rocky headlands of northern Vancouver Island disappear behind my wake. Off to the east the Great Bear Rainforest’s snow-capped peaks are silhouetted against a darkening sky. Through the salt-water mist a chain of serrated islets and islands appears.

These islands form part of the southern boundary of the Great Bear on the west coast of Canada, separating two worlds. The one I’m heading towards is a lost world of kelp forests, rock, towering trees and ecological riches. South of here the forests have largely been converted to tree plantations. The paradise to the north represents more than half of Canada’s Pacific coast and much of the world’s remaining intact temperate rainforest. It constitutes more than 1,000 uninhabited islands, 2,000 river valleys hosting wild salmon, and one of the largest unexplored, unprotected marine ecosystems on the planet. I’m traversing the wide-open Hecate Basin, the body of water between Vancouver Island and Haida Gwaii and the northern coast of mainland British Columbia. It remains as inspiring, fascinating and mysterious for me as it did when I first ventured here 25 years ago as part of a research team assessing the region’s endangered river valleys.

On days like today it is difficult to imagine living anywhere else. Some colleagues from Pacific Wild, the conservation group I founded with my wife, Karen, sailed with me to Vancouver Island on our 14-metre (46-foot) catamaran Habitat, a 15-hour journey from my home on Denny Island, to pick up crew and supplies. Now a stable air mass is giving us a window of reasonable weather for a few weeks of underwater and offshore exploration. By voyage end we will finish up on Denny Island, in the traditional territory of the Heiltsuk First Nation and also the location of the research field station for Pacific Wild. For more than 20 years, the staff at Pacific Wild have been working on wildlife conservation campaigns to protect this coast and today we work primarily on developing marine protected areas and large carnivore research, as well as youth education initiatives and science-based advocacy campaigns. Pacific Wild also operates and maintains a large hydrophone network coupled with remote cameras to research the underwater acoustic world.

Idling alongside one of the many islands, we are visited by gangs of Steller sea lions and an occasional California sea lion. Car-sized elephant seals bask on the few pockets of gravel found in isolated coves, harbour seals bob out of the water and in each kelp bed sea otters drift on their backs. The air is filled with calls – shrieks, groans, barks, chirps, whistles. One large flock of rhinoceros auklets begins to dive, forcing the schools of silvery sand lance to the surface. Hundreds of other birds swoop towards this new activity. The water is soon black with acres of surf scoters and more keep coming in to feed. There is life simply everywhere.

Great Bear LIVE

The Great Bear Rainforest, one of the planet’s few remaining wilderness areas, is frequented by an abundance of marine mammals. Diana wants to share this unique place with the world by live-streaming video from underwater cameras.