Secret Lives of Angelsharks

Angel sharks have been known to humans for millennia. Aristotle was fascinated by them and thought, mistakenly, that they supported his early theories of hybridisation. One of the species, the angelshark, has all but disappeared from its European range and is now seen regularly only in the Canary Islands, where Eva Meyers has set her heart on unlocking its secrets before it’s too late.

Introducing angel sharks

Angel sharks are flat-bodied and peaceful sharks that live on the sea floor. Their tendency to lie buried under the sand and remain unnoticed, almost invisible, helps them to evade not only potential predators and prey, but also scientists, who have overlooked them for many decades. Not only that, this very special group of sharks has been repeatedly misidentified around the world: in some regions, angel sharks have been landed as rays; in other places, they have been confused with ‘monkfish’; and in several countries they are not considered worth reporting at all. Angels inhabit all our oceans and like other elasmobranchs (sharks and rays), they have a key function in the ecosystem. Unfortunately, despite their talent for making themselves invisible, angel sharks have been heavily affected by the intensified effort of demersal fisheries, particularly in Europe.

If we go back in time, three angel shark species – the angelshark, the sawback angelshark and the smoothback angelshark – inhabited the north-eastern Atlantic, the Mediterranean Sea and the Black Sea. Although there are no historical population estimates for these three species, data from research vessels and fishery landings suggest that there have been severe population declines over the past century. It is suspected that the causes for these declines were the intensification of fisheries, habitat loss and the species’ slow reproductive rates that make population recovery difficult. The three species have consequently been classified as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, making them some of the most vulnerble elasmobranch species in Europe.

There is one place in the Atlantic Ocean, across from the windy coast of Morocco, where it seems that various sharks and rays have found an ideal habitat in which to co-exist. Stingrays, butterfly rays, bull rays, devil rays and, in particular, one of these three angel shark species, the angelshark, are all residents of the Canary Islands. This archipelago is the only known location in Europe where divers can regularly share a dive with angelsharks.

Photo by Michael J. Sealey

A first angelshark

Gran Canaria, March 2014

What was I to expect from a shark that nobody could tell me anything about? What would I see? Would I even see anything? What was I to look for? And what chance did I even have of finding a mysterious shark that disappears into the sand, one that Aristotle described as ‘the shark that can change colour and mimic the pattern of the fish it hunts’? Questions whirled around in my head, making me at one moment anxious about how impossible my quest seemed and at the next thrilled at the potential for discovery.

I remember every moment of the day I saw my first angelshark. The water was freezing and my heart threatened to beat out of my chest. It had been a while since I had last dived and I didn´t really know Gran Canaria or anyone there. Quite simply, I didn’t know what to expect. But I had come as ‘the shark expert’, so at least it should appear that I knew exactly what I was doing! There was no point in searching for more information about angelsharks because there was so little available – only descriptions of dead sharks caught in fishing nets or kept in glass cabinets where they had remained for years, waiting for someone to notice them. Let’s face it, angel sharks are not considered the most sexy or exciting of the shark species – at least until recently.

On that memorable day I was with Tony Sánchez, who had offered to take me diving in a spot where he had seen many angelsharks before. Tony knew so much more about these sharks than I did. He told me that he found them lying under the sand in water that was only 10 metres (33 feet) deep. And it was still a good time of year to see them, so we might be lucky. Most divers that I’d met so far had told me that angelsharks prefer cold water. It was March and the water in the Canary Islands was between 17 and 19 °C (62 and 66 °F).

Photo by Michael J. Sealey

Angel shark or angelshark?

Angel shark is a general term for members of the family Squatinidae, whereas angelshark refers to individual species, such as the angelshark Squatina squatina, the sawback angelshark S. aculeata and the smoothback angelshark S. oculata.

Photo by Michael J. Sealey

At a sheltered bay called Sardina del Norte, we got into the water and swam for about 20 minutes before Tony stopped and pointed at the sand. I looked at him and looked at the sand, then back at him. I could see he was laughing. I looked at the sand again and still I couldn’t see anything. Was he making fun of me? He kept pointing at the sand and finally lifted some of it. Out of nowhere, a flat shark with angel-like wings appeared. My first angelshark, a female about 1.2 metres (four feet) long, was looking at us but not moving. She let us approach. Slowly and carefully I moved nearer, afraid to spook her, but she stayed so calm that I felt confident enough to get even closer. Suddenly she ‘woke up’ and lifted her wings, the sand falling off her like glitter, and then she slowly swam away from us, floating gently through the water. That was when I became mesmerised by these enigmatic sharks and began to understand what makes the angelshark one of the most special creatures in the ocean. Despite all the hurdles that have arisen since then, I can look back at that moment and the many hours I have spent underwater with these sharks and know it has all been worthwhile.

Before I came to the Canary Islands, I started to look into this curious group of ‘flatsharks’ and in doing so moved away from the traditional scientific sources and dug into social media. At that time, I was finishing my Master’s degree in Germany and working as an intern for the Memorandum of Understanding on the Conservation of Migratory Sharks. A key experience in my short career, this internship opened my eyes in many ways. It gave me insight into the difficulties that scientists experience when trying to translate key data in a way that decision makers can understand and use for conservation and management purposes. Understanding this made me re-think my research questions and the ideas that I had for the project in the Canary Islands. I wanted my research to matter and to have a positive impact on the conservation of angelsharks.

When I started exploring the social media channels I was surprised to find a lot of angelshark images, and on following them up I noticed that divers in the Canary Islands regularly posted amazing pictures of angelsharks. The next thing I had to do was find out whether anyone was already working with these sharks. A search of the Internet produced no-one, but it did lead me to the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. I made a list of all the marine biology professors at the university and contacted each one, asking about shark research in the Canary Islands. Eventually one of them replied and invited me to come there and start working on angelsharks.

A few weeks after arriving on the Canary Islands, I discovered I was not the only one concerned about the conservation of angelsharks: the Zoological Society of London had been in contact with the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. Together we set up the Angel Shark Project as a collaborative initiative between the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, the Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig (where I was doing my Master’s thesis in Germany) and the Zoological Society of London.

Photo by Michael J. Sealey

Citizen science

The University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria set up a citizen science online database called Programa Poseidon that encourages divers and beach users to submit their sightings of any marine species they encounter during their recreational activities. The value of citizen science data has already been proven for studies into many species, initially those on land, but increasingly those in the oceans as well. We thus saw this online portal as a fundamental tool for gathering more data for our project. Almost every dive centre in the Canary Islands uses the angelshark in its logo, so at the same time we used the opportunity to engage divers in the conservation of their flagship species. Interestingly though, I was surprised that nobody seemed really aware of the angelshark’s conservation status, nor did they understand how special and unique is its presence in the Canary Islands.

Wanting to see where the sharks are and speak to the people who were reporting them, I decided to visit the islands where dive centres had submitted sightings. Slowly we established a network of collaborators and I ticked one island after another on my list, finally realising that angelsharks were present at all of them! In 2017 we published the results we had obtained from the citizen science database and the underwater surveys I was conducting at each island. For the first time we had an overview of the species’ distribution and preferred habitat in the archipelago. Our data showed a distribution gradient, with more sharks and more habitat suitable for them towards the central (Tenerife and Gran Canaria) and eastern islands (Fuerteventura, Lanzarote and La Graciosa). I had heard many dive instructors talk about seeing pregnant females at a certain time of year and about large male angelsharks coming closer to shore in winter. Finally, based on our results, we could confirm these observations. It seems that there is a mating season in the Canary Islands that overlaps with the winter months, while a breeding season extends through spring and summer.

We now have a better understanding about the distribution, population structure and habitat use of this shark. Of course, new questions then erupted. Where do the angelsharks go when the mating season is over? Can they move between islands? Are there specific breeding and nursery areas? Luckily, our curiosity has motivated us to develop new projects and start resolving some of these questions.

Photo by Michael J. Sealey

Photo by Carlos Suarez

In the mood for love

Lanzarote, November 2016

Since the project began, Lanzarote has been one of our key sites for tagging and at least once a year, particularly during the winter months, we visit the island. The chance of finding angelshark aggregations here, and perhaps observing angels mating, is pretty good. After one particular dive we joined Carlos, the owner of the dive centre Oceanos de Fuego, for a beer. Excited and still in my wetsuit, I described to him what we had just seen.

‘There was this male and then a female to our left, with another one behind. We saw three more at a depth of about six metres (20 feet). One of the females lifted her tail to entice the large male that was circling, but her charms failed to attract him. She remained in the sand, waiting for the handsome male to return, but he had apparently fallen for someone else. For a few minutes we followed him. My dive computer showed a depth of 17 metres (56 feet) and the visibility wasn’t good. I looked to my right and left and was happy to see that I wasn’t the only one with dirty thoughts – we all wanted to see some shark porn! Suddenly the male swam towards another female. What just happened? It took only a few seconds, but I think I saw the male biting into her pectoral fin, then a confusing scene of shark, sand, tornado, pirouette – and it’s over. Repeat, please, but a little slower!’

Photo by Carlos Suarez

Photo by Carlos Suarez

Baby angels

Tenerife, November 2017

A 15-minute drive from Santa Cruz, the capital of Tenerife, lies the popular Las Teresitas beach. It’s a long beach with golden sand, palm trees and a large selection of beach bars that compete to produce the best mojitos and reggaetón beats. What most people don’t know is that this used to be a rocky beach with sparkling volcanic black sand and strong waves breaking on its shore. For years, the volcanic sand was removed and used in construction projects on the island. Las Teresitas was losing its charm, so in the 1960s a new design for the beach was proposed. Tons of sand were imported from the Sahara Desert to cover the entire bay. To protect the beach and prevent the sand from being washed away by waves, two piers and a long breakwater were constructed, resulting in ‘the most beautiful beach on Tenerife’. At the same time, the new design created something that wasn’t foreseen in the original planning: the shallow and protected waters of Las Teresitas make a perfect marine nursery area where almost every Canarian fish species can be found in miniature. Protected from currents, waves and large predators, this natural aquarium has become a nursery for angelsharks too.

It’s 8 pm and we are getting ready for our survey in Las Teresitas. Thanks to the support of the Save Our Seas Foundation and CRESSI Sub, the Angel Shark Project has been surveying Las Teresitas for the past three years to understand the importance of this area for angelsharks and to learn more about their ecology and reproductive behaviour. We discovered Las Teresitas in 2014, while I was diving around all the islands to find out where angelsharks may be present. Felipe, who hails from Tenerife and is a student at the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria and the founder of Especies de Canarias, brought me here. He’s been coming to Las Teresitas to dive with his father since he was a child and has always known about the presence of angelshark pups at this beach. In fact, many beach users know about them, but pay no attention – except when somebody accidentally steps on one and gets a little nip!

When Felipe and I met, he insisted that I should come to Las Teresitas, saying it was unique and that I would not see this many angelshark pups anywhere else. And he was right! Since 2014 we have been coming to this beach for three consecutive nights three times a year to conduct surveys. ‘We’ are usually between eight and 10 people who come mostly from Tenerife and work as marine biologists or are students at the university, although we also get support from schoolchildren and other people who are interested in marine conservation but have no background in biology.

Photo by Carlos Suarez

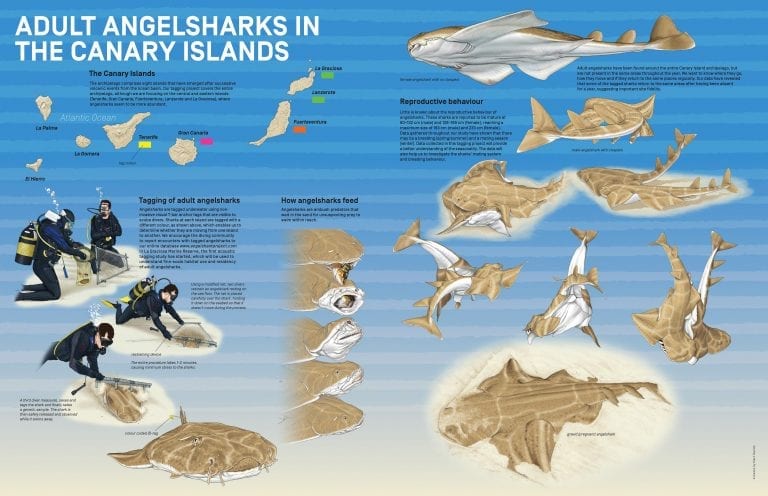

Angelshark tagging in the Canary Islands: The angel shark family was identified as the second most threatened of all the world’s sharks and rays after a global review of extinction risk by the IUCN Shark Specialist Group. Angel sharks were once widespread throughout the Atlantic Ocean and Europe’s seas, but are now extinct from much of their former range. The Canary Islands are the last known stronghold for one of the three Critically Endangered species: the angelshark, Squatina squatina. Even here it too is under threat and urgent action is required to protect it. For this reason, we are tagging angelsharks to increase our understanding of the biology and ecology of this shark so that we can inform conservation.

Artwork by Marc Dando

Photo by Michael J. Sealey

Since Las Teresitas is quite a large beach, we have divided it into four zones and each night we cover one or two of them in a two-hour survey. Our group is divided into the Water Team, in charge of snorkelling (sometimes diving) and catching the sharks, and the Land Team, which stays on the beach to work up the sharks that are caught and brought to the ‘tagging station’.

It’s not very difficult to catch angels if you use the right method. One of the advantages of working at night is that the sharks’ eyes shine when a light is pointed at them, revealing the presence of their owners. We have tried to find angelsharks during the day, but not only are they less active then, they are also almost impossible to spot. In fact, we believe that during the day they may even move into deeper areas. At night, however, the juvenile sharks come close to shore, sometimes into water as little as 20 centimetres (eight inches) deep. Here they lie, still and patient, until one of the millions of sand smelt fish swimming around makes the mistake of coming too close. Immediately, the juvenile shark extends its jaw and sucks the fish into its wide mouth. The fish doesn’t stand a chance. The shark then moves back to where it was and either remains as still as stone until the next victim swims by or buries itself in the sand, becoming one with its environment.

Nevertheless, our lights reveal the angelsharks and we catch them in small nets during their nocturnal feast. We measure and weigh them to estimate growth rates, which are currently unknown. Every shark caught is fitted with a PIT tag (microchip) so that we can identify individuals and record every centimetre and gram that they gain throughout the year. We are also able to monitor how long these sharks are staying at Las Teresitas. So far, our data indicate that juvenile angelsharks are using Las Teresitas as a nursery area for at least a year before moving away. The largest individual we have caught here was 55.5 centimetres (21.85 inches) total length, while the smallest was 23 centimetres (nine inches). The data also suggest that individuals that have reached the size of 40–50 centimetres (16–20 inches) are already a year old. Through long-term monitoring we are hoping to obtain more data on the growth rates and on the residency of the juvenile sharks in Las Teresitas. We also fit a visual ID tag to each shark so that future sightings of it once it has left the area can be reported to us via our online Angel Shark Sightings Map.

Photo by Michael J. Sealey

Photo by Michael J. Sealey

While working up each angelshark we take a genetic sample in the form of a clip from the back of the first dorsal fin. These samples are sent to Kevin Feldheim’s lab in Chicago where Kevin is helping us to look into the mating behaviour of angelsharks. Collected over a number of years, the samples will give us an idea about parentage and female philopatry (females returning to the same site to give birth to their young). We are now also taking samples of mucus to see if we can extract DNA from them, which could be used where angelsharks are less common. What we have learnt so far is that as well as being a special habitat for angelsharks, Las Teresitas is a nursery area for the species and is thus essential for its population in the Canary Islands. We have passed all our information on to the government of the Canary Islands and to the Spanish Ministry of Environment in the hope that Las Teresitas will become a protected area for angelsharks in the future.

Our work in Las Teresitas has raised even more questions than we started out with. We now want to know if there are other places like Las Teresitas – and if there are, the pressure to get protection measures in place is even greater! We have received support from various donors to investigate potential nursery areas at Tenerife, Gran Canaria, Fuerteventura, Lanzarote and La Graciosa. If we do find another potential nursery area, we plan to apply the same methodology that we are using at Las Teresitas.

On this survey, however, we have caught 38 juvenile angelsharks, 17 of which are re-captures. One of them we have named Silvi, in honour of our new student Silvia, who is working with citizen science data and looking at the habitat use of adult angelsharks in Fuerteventura. We have also caught only ‘larger’ individuals of between 30 and 45 centimetres (12 and 18 inches). Could this mean that the breeding season is over and only juveniles aged between six months and a year remain in the area? For now our job is done and we have earned a mojito and a shwarma at the dodgiest place in Santa Cruz to continue our discussions on these findings!

Photo by Michael J. Sealey

References

- Barker et al. 2016. Angelshark Action Plan for the Canary Islands. Zoological Society of London.

- Gordon et al. 2017. Eastern Atlantic & Mediterranean Angel Shark Conservation Strategy.

- Meyers et al. 2017. Population structure, distribution and habitat use of the Critically Endangered Angelshark, Squatina squatina, in the Canary Islands. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems

Photo by Michael J. Sealey

Adult tagging

Fuerteventura, March 2018

Fuerteventura is different from the other islands in the archipelago. It and Lanzarote are the driest and windiest of them all and lie closest to the coast of West Africa. Fuerteventura’s moon-like volcanic landscape and endless white beaches are stunning, while rich waters, cold currents and a large shelf around the island provide perfect conditions for angelsharks.

For the past four years we have tagged more than 60 adult angelsharks around four of the Canary Islands and some of the sharks have shown seasonal site fidelity to certain areas. We suspect that there are key aggregation sites at Fuerteventura, similar to sites we have discovered at Gran Canaria, Lanzarote and La Graciosa. One of the Fuerteventura sites is close to the Dive Centre Deep Blue on the eastern coast, an area that is heavily urbanised and a tourism hotspot.

To tag adult angelsharks, we have developed a unique underwater methodology that minimises stress for the shark. While diving, we can sex, tag and measure the shark and take a genetic sample. The unique colour code of each tag enables us to monitor the presence and movement of the sharks at and between islands. The tags are also visible to recreational divers, who can report sightings to our Angel Shark Sightings Map.

On this particular occasion, immediately after entering the water we find a 1.3-metre (four-foot) female shark resting in the sand. She has a very light colour pattern and is fully covered by sand. The water is only four metres (13 feet) deep and we are a few metres from the shore. The shark doesn’t move until she feels my needle in the base of her dorsal fin, injecting a coded tag: FV1379. As she whirls around she stirs up such a cloud of glittering sand that I can hardly see my own hands, but then I spot her as she glides away and disappears into the blue. During this particular dive, we tagged two more sharks and saw one adult male swim past. This is clearly a very important site for angelsharks and could be a key mating area, so we will monitor it closely over the next few years. Our next step for tagging is to introduce acoustic tags that will enable us to understand angelshark habitat use and movements better – watch this space!

Photo by Michael J. Sealey

Adult Angelsharks in the Canary Islands: Adult angelsharks have been found around the entire Canary Island archipelago, but are not present in the same areas throughout the year. We want to know where they go, how they move and if they return to the same places regularly. Our data have revealed that some of the tagged sharks return to the same areas after having been absent for a year, suggesting important site fidelity.

Artwork by Marc Dando

Photo by Michael J. Sealey

Plans and strategy

The need for a coordinated approach and effort to protect angelsharks throughout their range is critical and long overdue. We have been given this exclusive opportunity to work in the Canary Islands to make significant advances in angel shark conservation. With the knowledge gathered so far and a local network established, we felt ready to develop an Action Plan for the conservation of angelsharks in the Canary Islands, which was done together with the IUCN SSC Shark Specialist Group, the Shark Trust and Submon. During a stakeholder workshop, we explored the threats to angelsharks and discussed specific actions to mitigate these threats and recommendations for strengthening formal protection of the species.

The Action Plan has subsequently guided the prioritisation of our work, particularly regarding the threats posed to angelsharks by recreational and commercial fisheries. 2017 has also been the year for looking beyond what is happening in the Canary Islands. With a better understanding of the species and a growing network of angel shark enthusiasts, we have started to draw a picture of the situation throughout the species’ ranges. We have been involved in the development of the Eastern Atlantic & Mediterranean Angel Shark Conservation Strategy and jointly established the Angel Shark Conservation Network (www.angelsharknetwork.com). Here, a new collaborative citizen science database has been launched to collect data on the three Critically Endangered angel sharks – the sawback angelshark, the smoothback angelshark and the angelshark – throughout their ranges, including the Canary Islands. Anyone interested in working with angel sharks can join this network and new collaborative projects have been established. One example is our work with Natural Resources Wales in the UK.

I believe that by now you have probably begun to understand why I chose to work with angel sharks. Being a conservation biologist means that you do not just do science for the sake of doing science. In a generation where resources, time and political will are limited, science should focus on delivering the data that are needed to facilitate conservation and management decisions. I chose to work with angel sharks because I saw an opportunity to engage with a little-known group of species, where the data that I would be generating would directly benefit its conservation.

Photo by Michael J. Sealey

Acknowledgements

This article reflects a fraction of the extensive work the Angel Shark Project team has conducted together with partners, collaborators and volunteers. I would like to thank my partners in crime, Joanna Barker and David Jiménez Alvarado, with whom I jointly lead the Angel Shark Project. Many people are essential to the work we are conducting in the Canary Islands and although I would like to mention them all, to do so would take an entire page. I am grateful to the various funders that have facilitated the research in the Canary Islands, including the Disney Conservation Fund, the Shark Conservation Fund, Deutsche Elasmobranchier Gesellschaft, the Biodiversity Consultancy, CRESSI, the British and Irish Association of Zoos and Aquariums, the Mohamed Bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund, National Geographic, Oceanario de Lisboa, the Shuttleworth Foundation and the Ocean Tracking Network. The support of the Save Our Seas Foundation has been vital for this project and I owe much of my development as a scientist to it!

Angel of the Canary Islands

Although they grow to be 2.5 metres long, angel sharks are notoriously difficult to spot. They are flat, perfectly camouflaged – and also rare. Eva aims to learn about one of the few remaining populations of these enigmatic creatures.