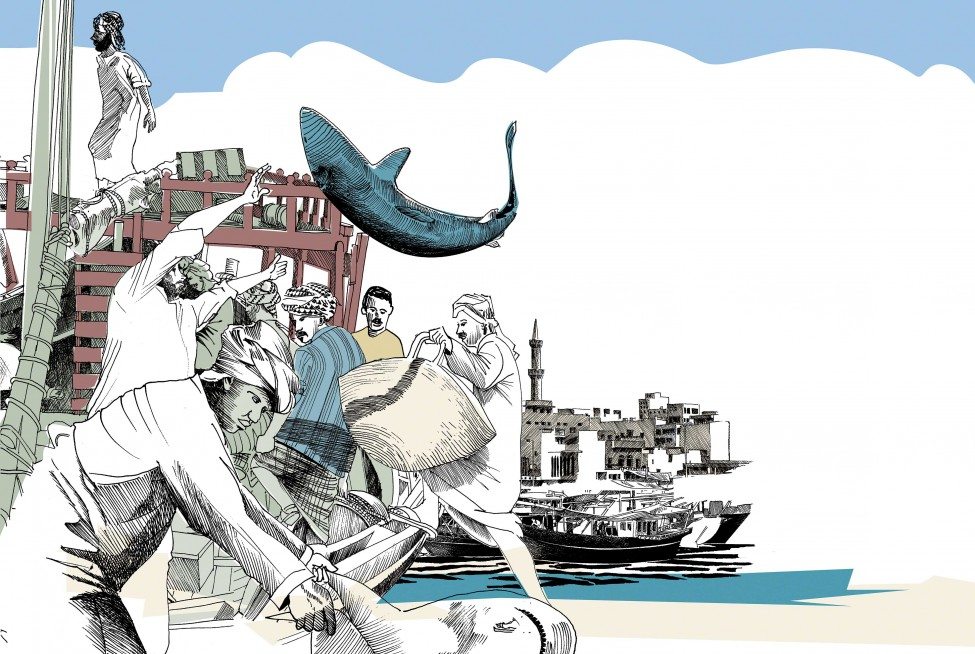

Sharks for Sale

Arabian Shark and Ray Fisheries

Protecting and managing shark and ray populations in the Arabian Sea is a huge challenge, explains Dr Rima Jabado, primarily because so little is known about them.

Reports of declining shark populations from around the world have proliferated in recent years, along with concerns that existing management measures are not going to be able to halt the sharp drop in shark numbers. But how do you manage shark populations in the face of uncertainty and how can you protect what you don’t know? These are the main questions that conservationists face when dealing with shark and ray fisheries in the Arabian Seas region.

This part of the world is well known for the unique biodiversity of much of its coastline and many of its islands, as well as for its tradition of pearl diving and its oil resources. More recently, it has been in the news for the contribution the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and the Republic of Yemen make to the shark-fin market in Hong Kong. In fact, for more than a decade these two countries have ranked in the top 10 – and sometimes even the top five – of the nations that export dried shark fins to Hong Kong, with yearly quantities reaching up to 400 metric tons.

In addition, five of the planet’s top shark-fishing countries – Iran, Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka and Yemen – border the Arabian Seas and together they contribute approximately 20% of the reported shark landings around the world. These numbers alone should sound an alarm about what could be happening to shark and ray stocks in the area. Yet this important region was, until recently, overlooked and to this day it is still understudied.

What most people don’t realise, however, is that the story of the Arabian Sea’s sharks and rays is much more complicated than it appears. Having always been utilised in the area, these animals feature in local traditions and contribute to the cultural heritage of many countries. Archaeological evidence from the UAE and dating back thousands of years shows the strong connection that the local communities had with the seas. Shark meat was an important component of the diet of many coastal inhabitants, oil from shark liver was used to waterproof dhows, the rostrum of sawfishes served as barbed wire around houses and even discarded fish parts were dug into date plantations as fertiliser.

More recently, as the demand for shark fins rose in Asian countries, fishermen around the Arabian Seas quickly realised that targeting sharks could be very lucrative. In fact, according to fishermen and traders from the UAE, Yemen, Oman and Saudi Arabia, demand from the Asian market has been the main driver for unsustainable shark fishing over the past 15 to 20 years. Fishermen in the UAE have confirmed that the abundance of sharks, the numbers caught and their sizes have all been greatly reduced – a sure sign of overfishing.