The call of the whales

More than a decade of surveying the whale populations of British Columbia’s northern coast has given Janie Wray a deep appreciation of the Great Whale Sea – and brought not a few surprises!

It was late summer in 2001 when Hermann and I travelled north along the Inside Passage of British Columbia, Canada, in our small, wooden, live-aboard boat Karmus. Our destination was Hartley Bay, a First Nation village on the province’s picturesque north coast, for a meeting with the hereditary chief Johnny Clifton and his wife Helen. We were going to ask for permission to build a land-based whale research station in Gitga’at territory.

The farther north we travelled, the more we felt as though we were going back in time. Giant cedar trees stood tall, their roots embedded in the rocky, barnacle-covered shoreline. Thick branches covered in giant bundles of green moss and lichen bent towards the water’s edge and were reflected in the calm, emerald sea. The midday heat might have tempted us to dive into this clear green water, but common sense prevailed; just dipping a foot into it would have sent shivers up our spines. At temperatures ranging from nine to 13 degrees, the water is extremely cold – cold enough to cause hypothermia in just 30 minutes.

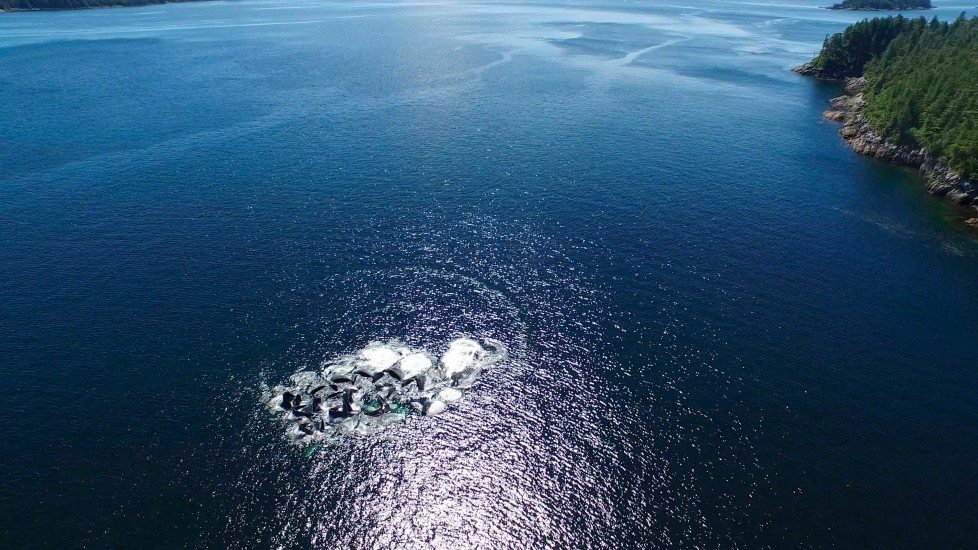

Many of the marine passages along this coast are fjords, carved out by glaciers long ago. For this reason, the depth of the water increases sharply just metres from the shoreline. On some days the water is so clear you can see all the marine life up to 10 metres (30 feet) down. Hundreds of bright purple and orange starfish cling to the underwater cliffs, surrounded by deep red sea urchins, white and green sea anemones and clusters of pink coral. The water bubbles along these shores with thousands of forage fish swimming through forests of golden bull kelp. Seals and sea lions are plentiful, basking in the sun on rock haul-outs or showing off their acrobatic skills underwater. In winter this area is known for fierce outflow winds that are so cold they can freeze the rain along the side of your boat – a very dangerous situation! When these winds subside, a south-easterly sometimes moves in at storm to hurricane force. During the summer months, though, the waters can be as peaceful as a giant pond.

We were extremely fortunate and our meeting with Johnny and Helen went very well. They embraced our idea for a whale research centre in their territory and shared with us their traditional knowledge of the whales in the area. They suggested we build in Taylor Bight, along the southern end of Gil Island. The next step – trying to raise funding to build in such a remote area – was a lot more difficult. There were no roads and no power. Everything would have to be brought in by boat and carried over a rocky shoreline, and we would need to generate our own power from water, wind and solar energy. Here you go back in time and every decision you make is ruled by weather, water and the need to be safe. We learned many lessons through trial and error, the most crucial of which was that nature decides who stays and who goes. We were fortunate that nature was on our side, and 15 years later we are still here on Whale Point.

Our initial goal with regard to research was to install hydrophones so that we could follow the underwater acoustic world of orcas and, with any luck, solve the mystery of their winter hangouts. Our research background is in orca dialects and how an acoustic tradition is passed on from the oldest female of a family to each new generation.

Cetacea Lab: A Voice For Whales

Janie and Hermann are working for the protection of Orcas and Humpback Whales in the Great Bear Rainforest by tuning into underwater hydrophones and deciphering the secret language of these majestic animals.