The Story of TED

It’s been a long battle, but gradually Dr Nicolas Pilcher is persuading the shrimp fishers, and government, of Malaysia that a simple device can protect turtles without detriment to their catch.

Sea turtles are iconic. They have the power to melt young hearts, to intrigue scientists and to mesmerise and impress the public. In Malaysia, where I am based and where I have devoted the past 20 years to finding solutions to sea turtle conservation challenges, the story is no different: sea turtles adorn tour buses, they are in just about every tourism brochure, they are on television adverts and in prime-time documentaries. They are featured in comic strips and on postage stamps. They are protected by more laws than in any other country in the world, as each state affords them protection over and above that provided by national legislation.

But they can hardly be considered ‘safe’, as a suite of pressures, both foreign and domestic, threaten their very existence. The leatherback turtle, once abundant, is now functionally extinct. The olive ridley is down to just tens of nests per year. The hawksbill is hanging on precariously. Only green turtle numbers remain stable, with several hundred turtles nesting regularly at a few rookeries and an impressive 5,000 nests annually at South-East Asia’s largest nesting site off Sandakan, in Sabah (Borneo).

Yet while Sabah’s turtles are currently abundant, they face some exceptional challenges. Turtle eggs are poached on all remote islands. Large adult turtles are caught by Chinese and Vietnamese fishing boats. Nesting sites are slowly being lost to coastal development. And by far the greatest threat to sea turtles in Malaysia is accidental capture in commercial and artisanal fisheries. Sea turtles have the unfortunate legacy of sharing habitats with some of our favourite foods, and of all the threats to their existence, the shrimp industry is perhaps the biggest. As shrimp trawl nets roll along the seabed they indiscriminately catch and drown numerous sea turtles – I estimate as many as 3,000 to 4,000 each year in Sabah alone.

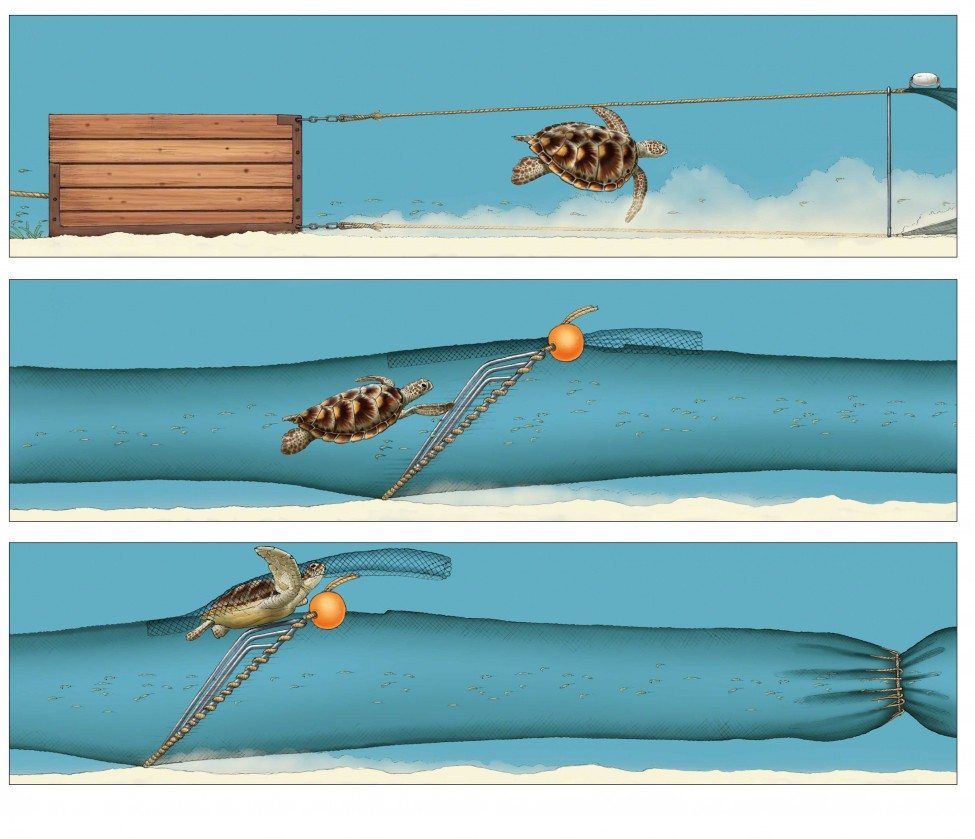

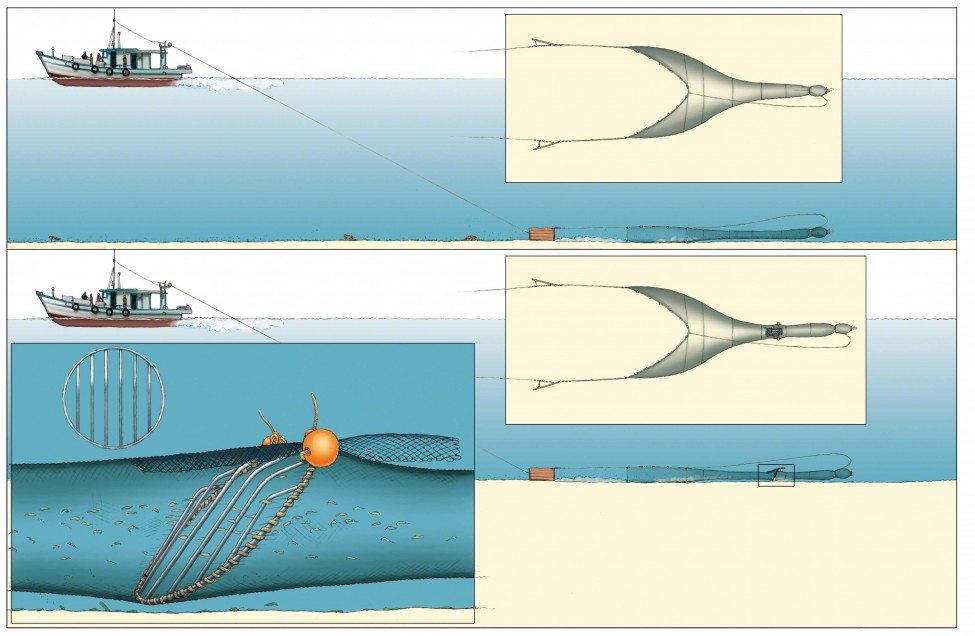

Putting an end to this unwanted by-catch has been my passion and inner driving force for the past decade. I started out as a research scientist studying the reproductive biology and early life-stage behaviour of sea turtles. Working with these fascinating creatures was almost addictive, with one exciting discovery leading to numerous new puzzles to be solved. But as the years went by I evolved – luckily faster than the turtles I studied – and devoted more and more time to finding ways to save my subjects from extinction. The situation for turtles slowly improved thanks to small management changes at national parks, but the threat posed by thousands of shrimp trawlers remained daunting. And yet a very practical and inexpensive solution existed in the form of Turtle Excluder Devices (or TEDs), which are fixed within a trawl net and allow a fisherman’s catch to be retained while turtles are excluded.

Sea turtles of Malaysia

Nick is on a mission to save Malaysia’s turtles. By convincing policy makers and fishermen to equip shrimp trawlers with Turtle Excluder Devices and studying the ecology of the turtles, he’s tackling the problem head on.