people safe, shark safe

A cluster of shark incidents and some outside-the-box thinking sparked a unique programme that is beneficial on so many levels. Lisa Boonzaier describes how it works.

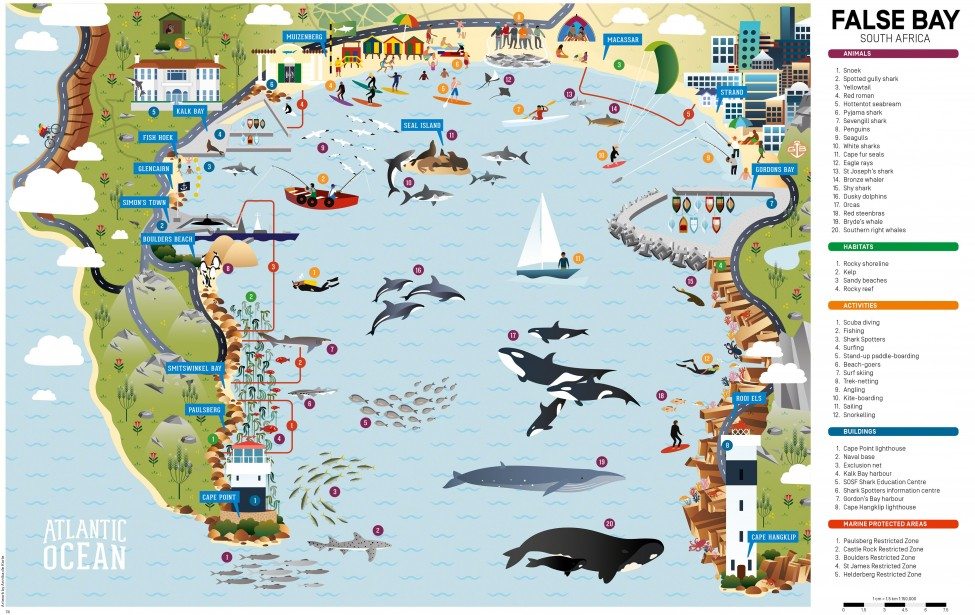

In the waters of False Bay, where the Atlantic Ocean curls around the south-western tip of Africa, marine life abounds. Gouged into this far corner of the South African coast, partly encircled by the Cape Peninsula and gaping southwards, False Bay has lush kelp forests, rocky reefs and sandy shores. A diversity of plants and creatures inhabit these realms and provide an assortment of food to the animals that feed on them. Throughout the bay, marine creatures and plants from the bottom of the food web through to its apex together play out the struggle of life and death, and have done so for millennia.

Just adjacent to this exceptional marine environment lies a more recently established but equally diverse community: the metropolis of Cape Town with its mishmash of urban areas and mix of people. Rounding the coast of False Bay from west to east, you will see the rugged mountainous wilderness of Cape Point; South Africa’s largest naval base in Simon’s Town; bustling upmarket towns like Kalk Bay; one of the best surfing beaches in the world at Muizenberg; and the sprawling and seemingly endless plains of informal housing, fishing harbours and the high-rise buildings of Strand that taper off into the holiday homes of seaside towns towards Cape Hangklip. All this on just 110 kilometres of coastline.

Together, almost four million people live in Cape Town, abutting the shores of False Bay. With this varied coastline right on their doorstep, Capetonians are not wont to stay on land, and scores of bathers, surfers, fishermen, kayakers, kite-boarders and divers are in the water year-round. This proximity of people and wildlife, while picturesque and exciting to imagine, can be problematic.

There are thousands of marine species, including 27 sharks, that play an important part in the balance of life in the bay, but in the minds of people there is one that overshadows them all: the great white shark. Even in the 1920s, the white shark population in False Bay was recognised as exceptional and the area’s shark abundance is almost unrivalled elsewhere. But what conditions support this profusion of white sharks? Seals, for starters. A consistent and abundant supply of them gives these marine giants – even though they are not yet fully adult – an ideal refuge to grow up in before they disperse into the wide ocean. ‘They’re not going to ignore a food source like this!’ says Cape Town-based marine biologist Dr Alison Kock. False Bay’s Seal Island, a small rocky outcrop east of Muizenberg, is home to the second largest breeding colony of Cape fur seals in South Africa and the white sharks that live here make up the second largest aggregation of the species. This means the area is one of the most vital for white sharks anywhere in the world.

SOSF Marine Conservation Photography Grant

The Save Our Seas Foundation believes that photography is a powerful tool for marine conservation. We invite emerging conservation and wildlife photographers who have a passion for marine subjects to apply for our 2016 grant. This is a unique opportunity for photographers to go on assignment, earn an income and gain experience under the guidance of National Geographic photographer Thomas Peschak.