Space In-ray-ders: Satellite Tracking Mantas

Satisfying as it may be, it’s not enough to know that manta rays aggregate at D’Arros Island. Where do they go when they’re not here? Lauren Peel and her team are beginning to find out.

When people think of the Seychelles they often imagine white sandy beaches and bright green palm fronds on small islands, not the millions of square kilometres of Indian Ocean that surround the island nation. But that is all I think of: the ocean and the incredible marine life in it – and the little-studied manta ray population that lives beneath the turquoise waves of the Seychelles. Researchers have spent more than 10 years studying the manta ray populations in other parts of the world, but next to nothing is known about this one. As the leader of the Save Our Seas Foundation and the Manta Trust’s Seychelles Manta Ray Project, I hope to change this by determining not only how many manta rays live in this part of the Western Indian Ocean, but also how frequently they visit the shores of the 115 islands comprising the archipelago.

As recently as six years ago, divers noted that manta rays aggregate almost year-round at D’Arros Island, a small coralline island on the Seychelles’ Amirantes Bank. Work soon began to photograph the unique spot patterns on the bellies of these animals so that individuals could be identified and counted. These same manta rays would soon become the focus of my PhD and while to this very day we are still monitoring their presence at D’Arros Island by means of photo-ID, our efforts were leaving a major question unanswered. Standing in front of the Save Our Seas Foundation D’Arros Research Centre (SOSF-DRC, the home of the Seychelles Manta Ray Project) and looking out over the shoreline towards the seemingly endless horizon, I couldn’t help asking myself, ‘With so much room to move, where do the manta rays go when they aren’t here?’

Unlike animals that live on land and move through a two-dimensional landscape, manta rays move through a three-dimensional environment, and if I were to track their movements at first hand I would need to grow gills. Fortunately, major technological advances over the past two decades have meant that I don’t need to start looking at getting a gill transplant just yet! Instead, to answer my question the SOSF-DRC team and I decided that we would use satellite tags to record and monitor remotely the movement patterns of the manta rays from D’Arros Island. There was only one downside; satellite tags are expensive! We’d be able to purchase the new technology, but only two tags. With little room for error, we knew that the field work ahead would be a challenge. But considering that this would be the first time a satellite tag would be deployed on a manta ray in the Seychelles, the excitement in the team was contagious.

The first hurdle was getting the tags to D’Arros Island. When I ordered them, the company warned that my required delivery date would be cutting it fine. Given the remoteness of D’Arros Island, flights can be spaced up to three weeks apart and if the tags weren’t with me when I got on that plane, there was a chance that we wouldn’t have them at all. The countdown was on. Five days to go … four days … three days – still no tags. Before I knew it, it was the day before I was meant to leave for the Seychelles and the tags still hadn’t been delivered. We were indeed cutting it fine! Thankfully though – just when I thought I would break the refresh button on my e-mail inbox – the notification came through. The tags had arrived! I got on the plane less than 18 hours later with two brand-new satellite tags packed safely in my luggage.

As with any field work, time was a precious commodity. In early November 2016, the Manta Trust’s Guy Stevens and I had 25 days on D’Arros Island and we wasted none of them; we’d barely touched down on the grassy runway before we were jumping into the water to photograph the mantas. After months of planning and countless hours on the plane, nothing could compare to being in the water with these mesmerising elasmobranchs. All the waiting and hurdles were forgotten every time I dove for an ID shot and turned to look back at an approaching manta. The rays’ curious nature and grace left me in awe, and as they passed overhead I took as many photographs as I could. Over the next few weeks we would become familiar with some of the smaller mantas that we saw almost every day, whereas other individuals we would see only once before they left the shallow waters surrounding the island. Our surveys formed a critical component of our understanding of which mantas appeared to be resident and which were likely to travel away from the island, so we watched and waited. The timing – and the mantas – needed to be right for our tags.

SOSF D’Arros Research Centre

A biological field station based on D’Arros Island in the Amirantes Group, Seychelles, the SOSF D’Arros Research Centre (SOSF–DRC) conducts research on the pristine D’Arros Island and St Joseph Atoll and the waters around them. In recognition of the islands’ outstanding natural values, the research centre was established in 2004 and tasked with becoming a regional centre of excellence for marine and tropical island conservation. Initially, collaborations were established with local and international institutions and baseline ecological surveys were conducted in the various habitats. Over the ensuing years an increasing number of research projects and monitoring programmes were implemented in response to questions raised by the baseline surveys and by visiting scientists. More recently, the centre expanded its activities to include ecosystem restoration and environmental education.

Today the SOSF–DRC boasts the longest-running nesting turtle monitoring programme in the Amirantes and the most detailed and technically advanced coral reef monitoring programme in the Seychelles, making use of techniques such as stereo-video photogrammetry, photoquadrats, remote underwater video systems (BRUVs) and visual census. The research centre also maintains the largest acoustic receiver array in the Seychelles, which monitors the local movements of sharks, manta rays, stingrays, turtles and fish. Since its inception in 2004, the centre has initiated no fewer than 36 research projects in collaboration with more than 26 conservation institutions. The projects have resulted in 10 peer-reviewed scientific papers, one PhD and one MSc dissertation, five conference presentations and 27 scientific reports.

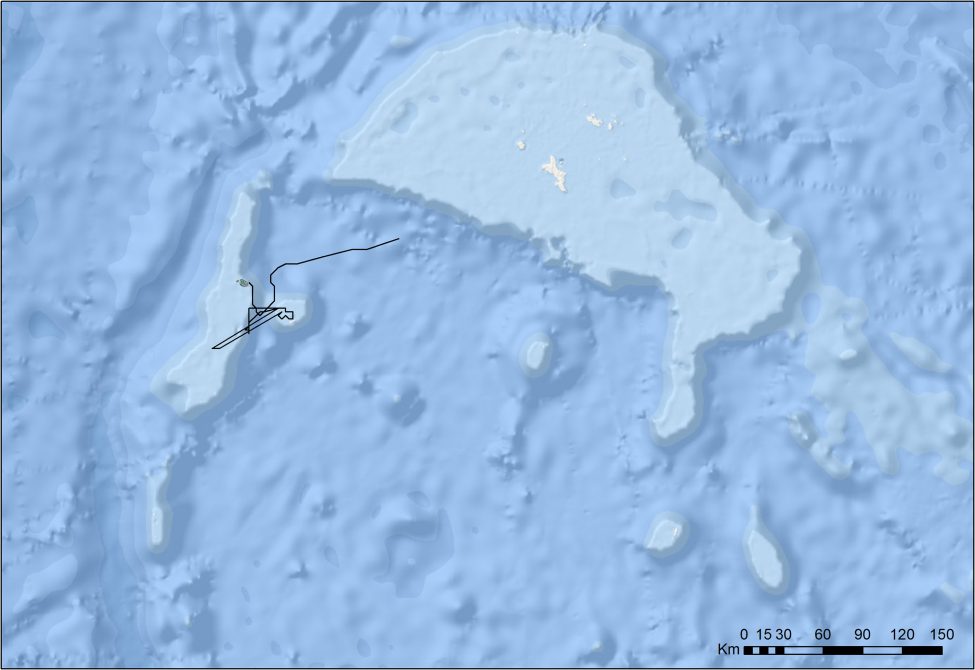

![The satellite track path of Medusa, a 3.6 m wide female reef manta ray, from D’Arros Island, Seychelles. Circles transition from green through to red to indicate Medusa’s travel path over time. Medusa travelled approximately 400 km during the 59 days that she was tracked, spending the majority of her time within the Amirante Island Group [map] before beginning a journey towards the main Seychelles Bank.<br />

© World Ocean Base – Esri, DeLorme, GEBCO, NOAA NGDC, and other contributors](/wp-content/uploads/SOSMag-Iss08-InsideStory-Art03-Map002-©LaurenPeel-SOSF-Copyright-Medusa-Amirantes-975x670.jpg)